Guarayu. A revised dictionary by Alfred Hoeller

by Swintha Danielsen and Lena Sell and Lena Terhart

The Guarayu language and its speakers⇫¶

Haga clic aquí por el texto en español/castellano

Introduction to Guarayu⇫¶

Guarayu is a Tupí-Guaraní language spoken by more than 7000 people in the lowlands of Bolivia, in the Guarayos province, Santa Cruz department.1 There are three varieties that differ in stress placement and vocabulary, as well as pronunciation of a number of words; the varieties spoken in Urubichá and Salvatierra have penultimate word stress, the dialect that is spoken in the department’s capital Ascensión de Guarayos, as well as in San Pablo and Yotaú, has predominant final stress, and speakers of the Yaguarú and Cururú dialect place stress sometimes on the antepenultimate syllable.

The ISO-code for Guarayu is gyr and the glottocode is guar1292. In Spanish, the language is called Guarayu, the ethnic group Guarayo, in the language itself both is spelled Gwarayu, according to the current orthography (Aeguazu et. al 2003; cf. orthography). In fact, the name "Guarayo” is not the original ethnonym of the group, however, there have been many speculations and reanalyses of the word, so that the interpretation that it means "yellow people” prevails among the Guarayo (see also Nostas, coord., 2007). This rumour has a history:

… d’Orbigny says […]: ‘Guarayo, like Guaraní […] means warrior’. And he adds: ‘F[ather] Lacueva believes that this word, pronounced Guarayu by the indios, comes from guara, nation, and yu, yellow, because they are whiter than the others. But the Guarayo don’t explain it like this’. (Combès 2014: 379, our translation)2

While d’Orbigny still notes that the Guarayo did not use this interpretation, nowadays it has developed into a widely accepted modern legend. However, it is true that "Guarayo” is a term that was applied to different ethnic groups: first and for all, it was used for Guaraní-speaking groups, like the Chiriguano and the Guarasugwe, but it was also used as a synonym for "savage” and addressed people like the Ese Ejja (a Takana language group in Northeast Bolivia). Ramírez (2010: 22, in Combès 2014: 383-384) proposes the most probable explanation of the word’s origin:

For him [Ramírez], this word would be of Quechua origin [wara] and would mean ‘the one who wears a loincloth’. (Combès 2014: 383-384, our translation)3

The Guarayu language has been recognized as an official language in the latest Bolivian Constitution (CPE 2008, Article 5), together with 35 other indigenous languages. Alongside the indigenous languages, Spanish is the official language of Bolivia, and it is also widely used in this region, so that most speakers of Guarayu can be considered bilingual.

Today, Guarayu is endangered, just like most other Bolivian indigenous languages. And this in spite of the fact that it is still used as the language of daily communication in some villages (like in Urubichá), and learnt by children and immigrants, which gives it at least a vital status in this linguistic island. Elsewhere (e.g. in Ascención de Guarayos), Guarayu is being replaced by local Spanish and even other indigenous languages of the highland migrants (Quechua and Aymara), and children only have a restricted competence, even though they learn it at school. After the implementation of the law of language policies in 2012, all employees in an administrative or public position (like municipality, administration, nurses, doctors, teachers) have to attend Guarayu classes and obtain a certificate of at least basic language competence.

Map: Bolivia and the Tupí-Guaraní languages (Danielsen & Gasparini 2015: 445)4

Classification of the Guarayu language⇫¶

Guarayu is a member of the large but shallow Tupí-Guaraní language family within the Tupian stock. On the basis of earlier classifications (Rodrigues 1984/85, Rodrigues & Cabral 2002), Guarayu was classified as subgroup II, together with Sirionó, Jorá and Yuki. However, the investigation by Dietrich (1990a: 111), which considers much more detail from Guaraní and Bolivian Tupí-Guaraní in particular, discovered that Guarayu can be classified – lexically and grammatically – as a language close to Guaraní in Paraguay and Bolivia, whereas Sirionó and Yuki are very innovative and can rather be regarded as links between the old Guaraní area and central Amazonia (Dietrich 1990a: 114). Guarayu is in fact very closely related to Guaraní, but it is more conservative, since it does not share two significant regular sound changes from Proto-Tupí-Guaraní with Guaraní: ts < Guarayu /ts/, but Guaraní /h/, and the final consonant

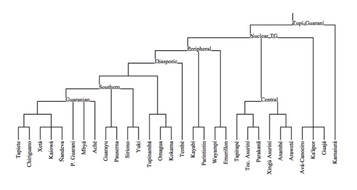

_r is maintained in Guarayu, but lost in Guaraní. The latest empirical comparison resulted in the classification of a Southern Subgroup of Tupí-Guaraní, of which Guarayu forms part (cf. Michael et al. 2015: 204) in a separate branch (see Figure 1). According to these latest findings, Guarayu is as closely related to Guaraní as the Sirionó-subgroup. Future investigation has to show if Guarayu and Guaraní are not in fact closer related, taking the very regular correspondences into account. To our knowledge, the Sirionó-subgroup has had more changes in isolation from Guaraní than Guarayu, but this needs to be proven with newer data.Figure 1: The subclassification of Tupí-Guaraní (Michael et al. 2015: 204)

History of Guarayu documentation and investigation⇫¶

After the Jesuits had been expelled from Bolivia in the late 18th century, the Bolivian lowlands experienced the second major wave of Christianisation, starting in 1823 and undertaken by Franciscans, in which the Guarayo were eventually missionized among others. The Franciscans Francisco Lacueva and José Cors were among the first to settle permanently in Guarayos and live there for decades (Cors [1875] in Mendoza 1957: 133; García Jordán 2006: 93). Cors’ ([1875]) notes describe the former ways of living and Guarayo mythology, and were therefore republished a number of times: in Mendoza 1957, Caurey & Ortíz García 2008, and with an analysis and interpretation from a Guarayo perspective by Urañavi (2009). Lacueva is reported to have produced a dictionary and a grammar of the Guarayu language. The grammar has recently been found in a copy by another Franciscan (Manuel Viudes 1841, publication in process by Dietrich & Danielsen), but the dictionary may have gotten lost.5 These early data on Guarayu facilitate the investigation of internal language change in the last centuries (cf. Danielsen 2018). After some translations of Catholic texts, there are two more grammar publications: the one by Priváser (1903) is a modern adaptation of Lacueva/Viudes grammar, while Hoeller (1932b) is the first detailed modern grammar on Guarayu, qualifying as an important linguistic work. No other grammar has been published on Guarayu since, with the exception of a grammar sketch by Armoye (2009). Hoeller (1932a) also published an extensive dictionary in Guarayu–German, which is the subject of publication here, so that more details are given in source of the data and adaptations. A good reference dictionary for Guarayu–Spanish and Spanish–Guarayu has been published by the Sociedad Bíblica Boliviana (ed., 2005). The latest publication of a small dictionary Guarayu-Spanish is Aeguazu (2018).

Guarayu documentation⇫¶

In 2007 (Nostas, coord.), a collection of Guarayu interviews was published in Spanish, focussing on various relevant cultural issues. However, disrespecting a few specialized or comparative publications considering the Guarayu language (e.g. Dietrich 1990b, Crowhurst 2000), no detailed linguistic investigation had been undertaken recently. This led to the creation of a research project at the University Leipzig, Germany, called GIZAC – Gwarayu and the Intermediate Zone (Amazonia – Chaco, Bolivia) documentation project, run by PI Swintha Danielsen. The project was carried out from 2014 till 2018, funded by the ELDP (Endangered Languages Documentation Programme) and HRELP (Hans Rausing Endangered Language Project) with the support from the Arcadia Fund at SOAS University of London, UK. Many Guarayu speakers have been involved in language documentation, and the project has received a very positive response by the Guarayo people. During the project, a vast amount of linguistic data was collected, transcribed, and translated, freely accessible at the ELAR archive. Further output of the GIZAC project are some publications in journals as well as a printed Guarayu dictionary by a Guarayu speaker (Aeguazu 2018); and one of the important long-term projects has been the digitization of the Hoeller (1932a) dictionary for a wider public. A very useful output of the project is also a Guarayu keyboard for computers and mobile phones, which was created by the team members. Since the Guarayo people communicate in their language in digital media, this has been of high relevance. A number of projects are still in process and will be published in the upcoming years.

Source of the data and adaptations⇫¶

Source information⇫¶

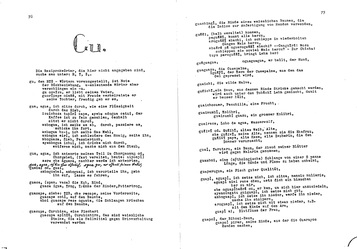

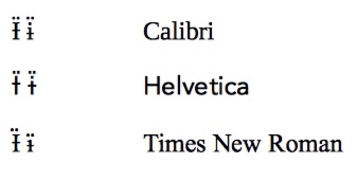

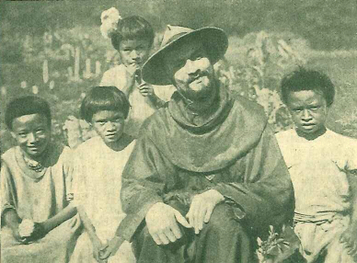

The data of this dictionary has been excerpted from two dictionaries by Alfredo Hoeller (or Alfred Höller, cf. Images 1 and 2), an Austrian Franciscan priest who lived in Ascención de Guarayos from 1929 to 1940, with one year in Yaguarú (1930). The main source is his Guarayu–German dictionary, which was published in 1932 (Hoeller 1932a) – see Image 3. The Hoeller (1932a) dictionary is a book in typewriter script with 336 pages. Each entry is, generally, accompanied by at least one, but often by many examples, and some minor grammatical information. A few entries, translations, and examples were added manually by the author; they form part of the regular print edition.

|

| |||||

| Image 1: Höller in Ascensión (Höller 1931: 43) | Image 2: Höller with Sirionó children in Santa María (Höller 1932: 27) |

Additionally, we used the data from Hoeller’s manuscript of a Guarayu–Spanish dictionary from 1929 (Hoeller 1929), which was only available to us in form of a rather weak black and white photocopy – see Image 4. This unpublished manuscript with 157 pages in typewriter script only contains the Guarayu entries with a Spanish translation, but no examples. In between the entries, there are a few handwritten notes by unknown author(s), which differ in style from Hoeller’s handwriting, so that we could only take them as extra information, and do not include this in the source citations of the entries in our published dictionary, with the only exception of cases where Hoeller definitely made a spelling mistake.

Image 3: Sample pages of Hoeller 1932a: 78-79

Image 4: Sample pages of Hoeller 1929: 10-11

Data transformation⇫¶

The digitization of the dictionaries was done as part of the GIZAC project (2014–2018) and then further elaborated until 2019 for Dictionaria. The process of digitization can be subdivided into the following steps with the people involved listed in parentheses:

- Scanning the dictionary Hoeller 1932a. (Clarissa Lohr)

- Manual copies of the entries of Hoeller 1932a with examples into Toolbox (TB), addition of English and Spanish translations. (Lena Terhart, Lena Sell, Roberto Herrera, and Marie-Luise Schwarzer)

- Manual copies of the entries of Hoeller 1929 into TB, addition of English and German translations. (Lena Terhart, Lena Sell)

- Joining of the two TB files and automatic selection of the first example of each entry for the output dictionary, merging of duplicate entries. (Lena Terhart, Lena Sell)

- Adapting all Guarayu material to the current orthography. (Lena Terhart, Lena Sell, Swintha Danielsen)

- Correction of Guarayu words and Spanish translations by Guarayu speakers. (Ruthy Yarita, Miguel Guayarabey, Pedro Yaquirena, Julia Bischoffberger, coordination Lena Sell, Lena Terhart, Swintha Danielsen)

- Export of images from the scanned file of Hoeller 1932a of the single entries. (Lena Sell, Lena Terhart)

- Collection of audios for a number of entries. (Swintha Danielsen, José Luis Cuñapiri, Elena Cuñapocayai)

- Preparation of the final TB file for export. (Lena Sell, Swintha Danielsen, Lena Terhart)

We created a Toolbox file with entries for each lexeme with its examples as written down by Hoeller, we added information about parts of speech and semantic domains, and added translations into English and Spanish – in many cases specific lowland or regional Bolivian Spanish, e.g. for animal and plant names, (and German for Hoeller 1929), and adapted the Guarayu parts to the modern orthography.

All Guarayu data and the Spanish translations were revised and corrected by native speakers of Guarayu in Bolivia. They were trained in using the programs Toolbox and Elan during the GIZAC project. Many entries had to be changed, because they consisted of inflected or transparently derived forms, rather than stems. These were analysed and changed to stems and minimally derived stems. The most frequent derived forms were maintained, since we can argue for certain degrees of lexicalization (see grammatical notes for derivational strategies in Guarayu). In contrast, we also included many entries that are only subentries or examples under a main entry in Hoeller (1932a); they may be main entries in Hoeller (1929), though, or their meaning deviates from the stem so much that the words were also integrated as separate entries in this dictionary. An important factor that also played a role here was the frequency of use of the words, according to the speakers.

Data representation⇫¶

Many of the entries in Hoeller’s dictionary (1932a) contain various examples. At least one of these examples was chosen per entry and retained in the dictionary. The remaining were stored in a separate file to be analysed at a later date. The complete set of examples can be found in the attached images of the original entries.

Additionally, audio files were recorded for about a fifth of the entries. These audios were produced in Urubichá by Swintha Danielsen with the Guarayu speakers José Luis Cuñapiri (where cited abbreviated as JLC) and Elena Cuñapocayai (abbreviated ECP) –the latter predominantly for a some female forms. Many of these audios contain the basic lexical entry and the inflected forms given in the paradigm field of the entry. One of the reasons why not all entries could be audio-recorded was that a number of lexemes as given by Hoeller are obsolete today. If a word was completely unknown or not used anymore by at least the speakers’ grandparents, we have not recorded it. However, this does not imply at all that the missing audios relate to obsolete words. The audios are mainly meant to accompany the complex impression of the language sounds and shall be regarded as exemplary items rather than a complete archive. The total number of audio files is 643.

In this edition of the dictionary, we have not added new entries consistently, but this may be done in future by considering all the examples from the dictionary. However, due to the changes of the forms into their stems or derived stems after consistency checks and corrections with the speakers, the entries of our dictionary do not all coincide with Hoeller’s entries. Productive grammatical affixes are also dictionary entries and represented as bound forms with a hyphen, in case they are orthographically presented as parts of word. In Hoeller (1932a), these may be presented as words or particles, or only as parts of words in Hoeller (1929).

Additional information that is given in each entry – where available or applicable – are dialectal or gender variation, paradigmatic examples with person marking, notes about the obsolescence of a word or semantic or grammatical changes, and cross-reference to a related entry. This information partly stems from Hoeller’s work and was partly added by us. The total number of entries is 3590 items. There are 2921 images from Hoeller (1932a). The complete scanned dictionary is also available for this dictionary. The photocopy of Hoeller (1929) is only attached as a complete copy, but no separate images are presented for the entries.

The dictionary is presented in Guarayu, Bolivian Spanish, German (Hoeller 1932a), and English, in order to address a broad public, but also in order to make these data available to the Bolivian national and, in particular, the Guarayu society. The German translations by Hoeller (1932a) have only been changed minimally, but not systematically.

The fields of special information, e.g. parts of speech and semantic domains, are given in detail in types of special information below.

Orthography⇫¶

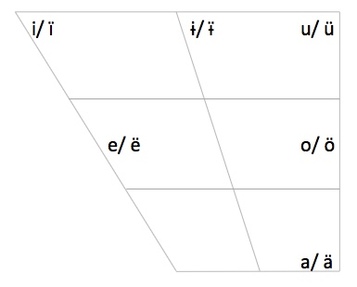

In this dictionary, we use the modern Guarayu orthography that was proposed by the speech community (Aeguazu et al. 2003). The Guarayu alphabet consists of the following graphemes:

a, ä, ch, e, ë, gw, i, ï, ɨ, ɨ̈, k, kw, m, mb, n, nd, ng, ñ, o, ö, p, r, s, t, u, ü, v, y, ’ (kunga)

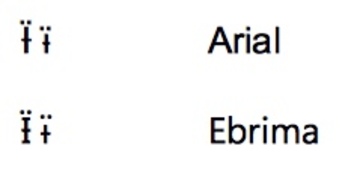

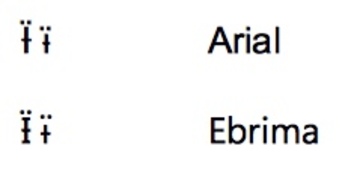

The nasal vowel ɨ̈ may not always be represented correctly in any browser. This problem is related to the fact that it is a complex grapheme with no single Unicode yet. The font of the CLLD website is Helvetica, and we have noticed problems with this font. The diaresis ( ¨ ) should replace the single dot and not co-occur, compare the two images.

|  | ||||||||

| Image 5: This is what it should look like | Image 6: Possible mistakes in representation |

Correspondences and changes from the graphemes used by Hoeller are listed in Table 1:

| phonological value | Hoeller 1929 | Hoeller 1932a | modern orthography |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | a | a | a |

| ã | â | ã | ä |

| tʃ | ch | ch | ch |

| e | e | e | e |

| ẽ | ê | ẽ | ë |

| gʷ | gu | gu | gw |

| i | i | i | i |

| ĩ | î | ĩ | ï |

| ɨ | ǐ | ì | ɨ |

| ɨ̃ | ý | ỹ | ɨ̈ |

| h | h | h | j |

| k | c, qu | c, qu | k |

| kʷ | cu | cu | kw |

| m | m | m | m |

| mb | mb | mb | mb |

| n | n | n | n |

| ɲ | ñ | ñ | ñ |

| nd | nd | nd | nd |

| ŋ | ng | ng | ng |

| o | o | o | o |

| õ | ô | õ | ö |

| p | p | p | p |

| r | r | r | r |

| ts ~ s | z | z | s |

| t | t | t | t |

| u | u | u | u |

| ũ | û | ũ | ü |

| β | b, v | b, v | v |

| j | y, (i) | y, (i) | y |

| ʔ | unmarked, and inconsistent marking by - (hyphen) or h | unmarked, and inconsistent marking by - (hyphen) or h | ’ |

Table 1: The different orthographical representations of Guarayu

Some explanations concerning the representation of sounds and their interpretation shall be given. First of all, it is noticeable that the grapheme <s> in the modern orthography is in fact pronounced as an affricate, or at least with almost affricative quality [ts] (see also Guarayu genderlect for possible genderlect variations). Nasality of vowels, and even to some degree of consonants, cannot be regarded an absolute fact, neither in this dictionary, nor in any way of representation. Even though nasality may have been represented on the respective vowels in the orthographies in Hoeller (1929, 1932a), this is either not always the case and instead – or in addition – marked by a following nasal consonant. Even in today’s orthography, this is not always consistent. The word [ãŋwEr] or [ãŋwEr] ‘spirit, soul, ghost’ is either spelled ängwer, ägwer, or angwer in 2019.6 What adds to the complexity of representation, is the fact that nasality has been on decline since Hoeller composed the dictionary almost one century ago. The variation of <m> and <mb> is a characteristic of Tupí-Guaraní; the sounds are reconstructed as one single sound *m for Proto-Tupí-Guaraní, which evolved into [m] and [mb] in all Tupí-Guaraní languages (cf. Rodrigues 1984/85), but phonemically it has to be regarded as a bilabial nasal [m] with possible co-articulation [mb]. While some occurrences of <mb> may be lexicalized, in most the choice of either sound is predictable: <m> occurs in nasal and <mb> in oral environments. The same holds, to a much lesser extent in Guarayu, for [n] and [nd].

The representation of the bilabial fricative

The glottal stop was generally not represented in Hoeller’s data, even though it has a partly phonemic status. Therefore, two adjacent open syllables with the same vowel, with the second one starting with a glottal stop are not differentiated from a long vowel, – as in so’o ‘meat’ spelled <zoo> in Hoeller (1932a: 348). Sequences of two different vowels could represent diphthongs or two syllables in Hoeller’s data. Nonetheless, in a few cases, Hoeller used <h> to represent a glottal stop: u’u ‘arrow’ is spelled as <uhu> (Hoeller 1932a: 267) or <huhu> (Hoeller 1932a: 85, 1929: 35). In other cases, the glottal stop between two vowels was marked by a hyphen, separating the word, as e.g. in ari’i ‘pimple’ <ari-i> (Hoeller 1932a: 32); or alternatively, words were simply split into two, such as (a)mbo’ɨpɨ’a ‘(I) thicken’

We are very confident with most of the expert assessments, however, variation is and was possible. Spelling variants are given for many entries, right underneath the lexical entry and the representations in the historical sources. If the variant depends on the dialect, or on the time, this information is detailed in the respective fields (dialect or genderlect info). Since, apart from an alphabet proposal, the orthographical conventions are still under construction for Guarayu, there are no consistent rules for spelling words separately or as one. We have tried to apply the proposed rules (under development by Danielsen in collaboration with the ILC Gwarayu),7 on the one hand, and on the other hand, we adjusted to the most common conventions or uses of words and the degree of lexicalization. In tendency, we can argue that Guarayu morphemes are spelled in an increasingly analytic way, which may have to do with the transparency of their meanings, but also be influenced by Spanish orthographical conventions and the infrequent compounding there.

Types of special information⇫¶

The dictionary contains different kinds of fields: the lexeme, variant or alternative form, part of speech, semantic domain, translation into English, Spanish, and German, information on dialectal variants, gender variation, use and obsolescence, examples in Guarayu with English, Spanish, and German translation, a picture of the original entry of the 1932a dictionary with German translations, and in some cases an audio recording of the word. Each entry also contains the reference to the original source and the original form and orthography of the entry in Hoeller’s dictionaries. For this edition, it was unfortunately not possible to include pictures of the entries in the 1929 dictionary, which we also hope to find in a better quality in the future.

The following categories for parts of speech are used in the dictionary, presented in alphabetical order:

| Abbreviation | Part of Speech |

|---|---|

| adv | adverb |

| conj | conjunction |

| dem | demonstrative |

| exp | expression |

| ideo | ideophone |

| intj | interjection |

| n | nouns and stative verbs that require the che-paradigm ("set 2 markers”) in personal inflection |

| num | numeral |

| part | particle |

| postpos | postposition |

| pref | prefix |

| pron | pronoun |

| suff | suffix |

| v | transitive and intransitive active verbs that require the a-paradigm ("set 1 markers”) in personal inflection |

| v.der | derived verb forms, such as participles |

Table 2: Parts of speech in the Guarayu dictionary

The following semantic domains are used in the dictionary to categorize the entries tentatively:

| semantic domain | comment |

|---|---|

| activity activity - motion activity - sound activity - speech activity - perception activity - imperative | used for verbs |

| action | nouns for actions, e.g. race |

| state state - quality state - size & shape | used for stative verbs that require the nominal inflection (_che_ - paradigm) |

| animal animal - mammal animal - bird animal - amphibian animal - fish animal - insect animal - reptile animal - mollusk animal - crustacean animal - body.part animal - myriapod animal - offspring animal - house animal - product | |

| plant plant - tree plant - palm plant - liana plant - herb plant - fruit plant - seed plant - part plant - aquatic plant - cactus plant - shrub | |

| fungi | mushrooms |

| object object - household object - vehicle object - music object - hunt object - tool object - container object - adornment | |

| material | |

| clothes clothes-adornment | |

| construction | including house, parts of the house, other buildings such as stables, etc. |

| food & drink | |

| human human - profession human - emotion & cognition human - communication | |

| name | proper names of persons and places |

| kinship | |

| body part body part - liquid body part - organ | |

| body.function | |

| religion & spirituality | |

| health | |

| culture | culture - specific terms like dances etc. |

| social relations | neighbours, sexual relations, gossip, etc. |

| environment | landscape and environment |

| weather | |

| cosmic phenomena | sun, moon, stars, sky, shooting star, solar eclipse, etc. |

| time | |

| location | places |

| sound | |

| size & shape | nouns that refer to size or shape of things |

| quantity | |

| manner | adverbs |

| grammatical grammatical - clause grammatical - interrogative grammatical - person grammatical - discourse grammatical - deictic grammatical - tense grammatical - locative grammatical - negation grammatical - polarity | |

| property | properties of things (e.g. smell) |

| symptomatic appellative | for interjections |

| colour | |

| other |

Table 3: Semantic domains used in the Guarayu dictionary to categorize the entries

We use the paradigm field to give short information about the grammatical behaviour of verbs and nouns (see forms of stems and morphology of predicates), i.e. a general classification of the R-S-T-0 roots, and the inflectional behaviour of the lexeme as either following the verbal a-paradigm or the nominal che-paradigm. This information is partly taken from the sources and partly elicited from the Guarayu speakers. If there is an audio file connected to entries with information about the paradigm, then the audio also presents this, at least the form for 1SG, but mostly 1SG, 2SG, and 3SG.

Additional information of interest can be found in a general comments field. This field is used to show if the form is different in 2019, if it is a compound, or any other relevant information concerning the main entry. Not every word could be triple-checked with the speakers, however, we tried to carefully check all words that speakers had doubts about. In case that none of the speakers knew the lexeme, we marked the entry as "not confirmed”. This should be understood as a remark on its present use, we do not make any claims about use in Hoeller’s times.

Grammatical notes⇫¶

For the Guarayu grammar, there are only a few references, as mentioned in history of Guarayu documentation and investigation above, so that these either only give insight to selective aspects of the grammar (Armoye 2009, Crowhurst 2000), or the publication is in German and not accessible to a wider public (Hoeller 1932b). The grammatical profile of Guarayu is very similar to the one of Guaraní, and since there is no modern reference grammar of Guarayu, we want to refer to those works (e.g. Gustafson 2014, Dietrich 1990b, and Dietrich 2010, 2018 for comparative descriptions). We will only give a short overview of some grammatical characteristics that are necessary to correctly interpret the Guarayu entries and examples, referring briefly to the phonological system and morphophonological changes (Guarayu phonology and morphophonology), to morphology and derivation strategies in Guarayu (forms of stems and morphology of predicates). Some basics of Guarayu syntax are explained on the basis of more complex examples (constituent order and postpositions), but a detailed analysis of Guarayu syntax is still missing.

Guarayu phonology and morphophonology⇫¶

Since stress placement is one of the decisive factors that distinguishes the three main dialects of the language (Urubichá – Ascensión – Yaguarú), it has been decided (Aeguazu et al. 2003) not to encode word accent in the orthographic system, unlike in Paraguayan Guaraní or Spanish. This decision does not pose a problem for speakers of the Urubichá dialect that usually has penultimate stress just like Spanish. However, some people from Ascensión feel discriminated by this decision, because word final stress, the most frequent stress pattern of their dialect – inherited from Proto-Tupí-Guaraní, and shared with Paraguayan Guaraní – is not easily recognized and pronounced by people with a strong background in the Spanish language. They fear that the Urubichá dialect will become the standard for Guarayu, at least concerning stress placement. Yaguarú has sometimes antepenultimate stress and will have to struggle even more in the future to maintain its stress pattern in relation to the stronger variants of Urubichá and Ascensión.

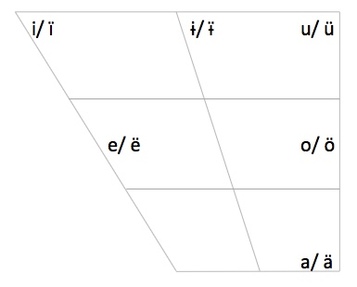

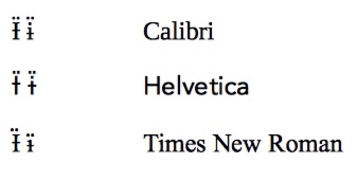

The phonemic inventory of Guarayu has been proposed tentatively by Crowhurst (2000), and the proposal can mostly be confirmed by our findings. Guarayu has a system of six oral and six corresponding nasal vowels, represented in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Vowel phonemes in Guarayu

Nasal vowels have a strong impact on the consonantal environment, because nasality generally spreads in both directions, so that the whole word becomes nasal, and generally the nasal syllable is stressed. Therefore, the representation of nasal vowels in the Guarayu orthography is essential. However, the place of marking nasality in a word is generally a matter of discussion. The dialect documented by Hoeller is the one from Ascensión with predominant word-final stress, which can be noticed especially by his placement of diacritics for nasality, as well as stress. We can argue that a nasal vowel usually attracts stress and it also causes nasalization of the unstressed vowels. Since word-final stress is a Proto-Tupí-Guaraní feature, we can find the original place of nasals due to stress placement in Guarayu of Ascensión: namely, if the stress does not fall on the final syllable, the phonemic nasal vowel is the one in the stressed nasal syllable. This original stress shift is overwritten by modern stress rules, so that at least the Urubichá variant tends to regular penultimate stress in spite of the nasality. The proposal to only mark one nasal vowel per word has been partly accepted, but in reality it causes trouble with the stress placement and subsequent discussions, which are related to the discussions about stress marking. One commonly observed solution remains the marking of nasal vowels on every syllable of the word.8

Another matter of variation is the presence or absence of additional nasal consonants after nasal vowels, as mentioned above in orthography. This variation and that of encoded nasal vowels have to be kept in mind when reading the dictionary.

Vowel length may have played a role in Guarayu in earlier times, however, it does not seem to be a strong factor at presence. It can be the case that certain stressed vowels sound longer than others. Vowel length has been reconstructed for Proto-Mawetí-Guaraní by Meira & Drude (2015: 280), and in Hoeller 1932a, we find very few items with actual long vowels that are not vowel sequences separated by a glottal. One example is the verb kwaa ‘know’, which can be distinguished from kwa ‘bind, tighten’, so that we have minimal pairs like aipokwaa ‘they are making me used to (lit. they make my hand know)’ and aipokwa ‘I tie his hand’, both incorporating po ‘hand’. Even though these long vowels cannot be confirmed today and the spelling and pronunciation seem to be indistinguishable – e.g. kwa ‘know, bind’ –, we keep this information in the dictionary for Hoeller’s times.

The phonetic consonants of Guarayu are summarized in Table 4:

| voiced +/- | bilabial | alveolar | alveolar-palatal | palatal | labio-velar | (labialized) | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plosives | - | p | t | k | kw | ʔ | ||

| + | gw | |||||||

| prenasalized plosives | - | (mp) | (nt) | (ŋk) | ||||

| + | mb | nd | (ŋg) | (ŋgw) | ||||

| fricatives | - | (s) | ||||||

| + | β | |||||||

| affricates | - | ts | tʃ | |||||

| nasals | m | n | (ɲ) | |||||

| vibrants | r | |||||||

| approximants | y | (w) |

Table 4: Guarayu phonetic consonants (slightly changed from Crowhurst 2000: 7)

As Table 4 shows by the many phonetic forms in parentheses, the consonant values change in certain environments, mostly related to nasal vowels, but sometimes also due to nasal consonants. These changes are generally expressed orthographically, as well.

The nasal consonants stand in a close relation to the seemingly prenasalized stops, which actually originate in nasals with a plosive offset coarticulation. Therefore we find allomorphs for the causative prefix as mbo- in oral, but mo- in nasal contexts. This can be transferred to many other parts of the language, i.e. a variation between m and mb (or n and nd) should not be taken as absolute realizations, but considered to be matter of variation on a continuum between orality and nasality.

The same also holds for the quite frequent approximant y – as e.g. in third person marking, where it is an allomorph of i, used before vowel initial roots –, which changes into ñ in nasal contexts. The nasal variant of the vibrant r may be perceived as n by non-speakers and non-native speakers, especially word-internally, while Guarayu speakers clearly identify a nasal r, and this is how it should be spelled. Some forms of nasal r have been documented with n in Hoeller, but this is mainly true for his earlier work (Hoeller 1929), while in the later dictionary, Hoeller shows much better knowledge of the Guarayu language (Hoeller 1932a). In most cases, Hoeller (1932a) gives us r, where Hoeller (1929) spells it n, as e.g. m(b)a’erä ‘Why?’ – mbaẽrã? (Hoeller 1932a: 114); mbaéna? (Hoeller 1929: 47). One example for a clear mistake is ñuvɨrïo or short ñurïo ‘two’, which is found as ñunio (Hoeller 1932a: 157); yunio (Hoeller 1932a:311); ñunio, yunió (Hoeller 1929: 67).9

Some morphophonological relations are straight forward, e.g. that a voiceless stop p can change to mb, or k to ng, in a nasal environment of derivation, compounding, incorporation, or other ways that may change stems. Two examples shall be given. Nouns are derived by nasalization from p- initial verbs, like poravɨkɨ ‘work (v)’ and mboravɨkɨ ‘work (n)’. The word minga’u ‘a thick soup made with corn or manioc flour’ derives from a morpheme for soup mï(m)- and k*a’u ‘flour’.

Other relations seem to be further fetched, but they exist, too. One such variation occurs with words that have a root initial s- proper – in contrast to the grammatical s- person marker addressed below in forms of stems and morphology of predicates. These words carry s- in their relational forms and ch- in the forms for 3rd person, or in derived gerunds or participles, such as vicho ‘for going (GER)’ > (a-)so ‘(I) go’; ichɨ ‘his/her mother’ > (che) sɨ ‘(my) mother’, and ichɨpe ‘his/her shovel’ > (che) sɨpe ‘(my) shovel’. Another lexicalized change of initial consonants is the nasalization of s- into nd, as e.g. in the causative derivations of s*ɨi ‘startle (possibly extinct root)’ < mondɨi ‘chase off’ and s**o ‘go’ < mondo ‘give (lit. make go to another person)’.

For historical changes, especially relating to phonological changes in Guarayu, please refer to Danielsen (2018).

Forms of stems and morphology of predicates⇫¶

Guarayu works on the basis of roots, which are not necessarily categorizable as parts of speech. We usually classify them as nominal by default, unless they take verbal marking of the a-paradigm (also known as "set 1 markers”) without any other derivation, except for a 3O prefix (i-/y-/ñ-). The distinctive factor that sets apart verbs from non-verbs is thus the kind of person marking by a verbal (a-paradigm) or active alignment and nominal (che-paradigm) or stative alignment. Pronominal reference distinguishes three persons for the singular (1SG, 2SG, 3), with no gender distinction, and four persons in the plural (1PL.incl, 1PL.excl, 2PL, 3PL). In general, the 3rd person stands for both, singular and plural, but the grammaticalization of a specific 3PL marker already started in Hoeller’s times. This can be employed for human subjects and tends to become obligatory today. In addition, today it is accompanied by a postverbal 3PL pronoun.

The "set 1 markers” (in the terminology of Jensen 1998: 498, cf. Table 5 below) are interpreted as verbal pronominal markers, and they mark the subject of the predicate. We call it the a-paradigm, after the marker of the first person singular a-. This set consists of prefixes only. There are two additional portmanteau prefixes for transitive verbs, marking 1st person acting on 2SG, and 1st person acting on 2PL (called "set 4-markers” by Jensen 1998). "Set 2 markers” are used for nominal predication. The set consists of pronouns for all persons except for 3rd, which is expressed by a prefix. We call it the che-paradigm, after the marker of the first person singular che. Nominal predication is typically used for possessive relations. In nominal predication, there is additional coreferential marking for the 3rd person in order to express that the 3rd person possessor of the nominal predicate is identical to the subject of the verbal predicate in a clause (called "set 3 markers” in Jensen 1998). Table 5 lists the different sets of person markers in Guarayu today:

| person | pronouns | verbal | nominal | ||

| set 1: a-paradigm | portmanteau | set 2: che-paradigm | coreferential | ||

| 1SG | che | a- | che | ||

| 2SG | nde | ere-(irregular/IMP e-) | 1>2SG oro- | nde | |

| 3 | a’e | o- | i-, y-/ ñ- s- | vɨ- (gwe-) o- | |

| 1PL.incl | yande | ya-/ña- | 1>2PL opo- | yande | |

| 1PL.excl | ore | oro- | ore | ||

| 2PL | pe | pe- | pe | ||

| 3PL | yuvɨreko | o-, yu-/ñu-, yuvɨro- … yuvɨreko | i-, y-/ ñ- s- (… yuvɨreko) | vɨ- (gwe-) o- | |

Table 5: Guarayu person markers in 2019

The formal differences with the morphemes as annotated by Hoeller are the following: 1) Hoeller follows the Guaraní tradition and uses a more nasal form, ñande, of the 1PL pronoun throughout his entire work. We cannot say for sure that this pronoun really had a more nasal pronunciation in former times, but we keep it as this form in the dictionary. 2) Even though Hoeller already shows a number of forms with 3PL marking, this was presumably just starting to grammaticalize in his times. Especially, the use of yuvɨreko ‘3PL (lit. they have)’ as a pronoun is a rather modern phenomenon and not commonly observed in older data. Hoeller did not recognize this special 3PL, or did not address it explicitly. 3) Hoeller still shows examples with the coreferential prefix of the 1SG gwi-/vi-, which does not seem to be used anymore today.

The remainder of this section is used to explain the different predication patterns found in Guarayu, followed by some notes on derivational processes.

Intransitive verbs take active alignment and use the a-paradigm for subject marking, as in (1):

| (1) | kui ‘fall’ (v): | a-kui, | ere-kui, | o-kui, | ya-kui, | oro-kui, | pe-kui | ||

| 1SG-fall | 2SG-fall | 3-fall | 1PL.incl-fall | 1PL.excl-fall | 2PL-fall | 3-fall | |||

| ‘I fall, you (SG) fall, (s)he falls/ they fall, we (incl.) fall, we (excl.) fall, you (PL) fall’ | |||||||||

Possessed nouns take stative alignment and the possessor is marked by the che-paradigm:

| (2) | po ‘hand’ (n): | che po, | nde po, | i-po, | yande po, | ore po, | pe po |

| 1SG hand | 2SG hand | 3-hand | 1PL.incl hand | 1PL.excl hand | 2PL hand | ||

| ‘my hand, your (SG) hand, his/her/their hand(s), our (incl.) hands, our (excl.) hands, your (PL) hands.’ | |||||||

Non-verbal predication takes stative alignment and works just like possession, but the words may often be translated as verbs or adjectives in other languages, as in the following example:

| (3) | e ‘eruct(ation)’ (n): | che e, | nde e, | i-’e, | yande e, | ore e, | pe e |

| 1SG eruct | 2SG eruct | 3-eruct | 1PL.incl eruct | 1PL.excl eruct | 2PL eruct | ||

| ‘I eruct, you (SG) eruct, (s)he eructs/they eruct, we (incl.) eruct, we (excl.) eruct, you (PL) eruct’ | |||||||

In fact, in Guarayu, one does not say ‘I eruct’ (active), but ‘my eructation’, or ‘there is an eructation to me’ (stative), treating the single argument like a possessor or, as we will see below, as an object. This is certainly related to less control of the semantic subject. Only very few roots can be used in one or the other construction, like e.g. ‘thirsty’, which can either have active alignment of the a-paradigm, referring to a possibly sudden and strong desire to drink, whereas the stative alignment of the che-paradigm is the more common way of saying ‘I am thirsty’, compare (4):

| (4) | ɨusei ‘thirsty’ (n/v): | che | ɨusei | a-ɨusei | (lit. | ɨ-u-sei) |

| 1SG | thirsty | 1SG-thirsty | water-drink.eat-desire |

Apart from those roots that take a 3rd person marker i- before an initial consonant and y- before an initial vowel in the che-paradigm, there is another class of roots that originally have an initial vowel, but in their relational forms with speech act participants (SAPs), they take the relational prefix r-, and in the 3rd person the relational marker is s-. Relational forms are also used in syntactic compounding. Guarayu speakers perceive the forms with r- and s- as lexical units, for which reason both forms can generally be found in the dictionary, in addition to the bare form or root with the initial vowel. We can argue that the r-/s-forms are relatively lexicalized and only recognizable without these initial consonants when e.g. incorporated or in morphological compounds (cf. Constituent order and postpositions). Many combinations of these bare forms with other lexical material (nominal or verbal roots) show a certain degree of lexicalization. A third prefix that is losing ground of productivity today, is t- for derivation of non-possessed forms (also nominalizing with verbal roots in Hoeller 1932a). Forms with this prefix most often led to lexicalized words with specified meanings. In other cases, t- can be the 3rd person marker of some kinship terms where we would expect s-. In Hoeller’s times, t- was almost fully productive, as it seems, even though the author may also have generalized it a bit too much. In example (5), a typical noun with the "R-S-T-0” variation is shown, as we call it in the dictionary:

| (5) | rova ‘face’ (n, R-S-T-0): | che rova, | nde rova, | sova, | (tova), | a-ye-ova-sei |

| 1SG face | 2SG face | 3.face | face | 1SG-RFLX-face-wash | ||

| ‘my face, your (SG) face, his/her face, a face, I wash my face’ | ||||||

The dictionary of Hoeller (1932a) lists all four forms ova, rova, sova, and tova, and this is true for most of the roots of this kind.10 We follow this convention instead of giving only one entry per root, since this is also the way these lexemes are treated in dictionaries that Guarayu people have produced themselves (e.g. Aeguazu 2018).11 In cases where we know that the paradigm is not fully realised, we reduce the grammatical paradigm information to R-S-0 or R-T-0. In a few cases, the roots may also occur in both paradigms, either with 3rd person s- or y-, generally with some semantic difference or depending on specific constructions. This information is specified as R-S-T-0-y.

Transitive verbs usually contain an obligatory slot for object marking, which directly follows the person marker for the subject. Regarding 3rd person objects, a similar behaviour of roots can be observed as described for nouns above: either the object is marked by i- (or yo-) before initial consonants or y- before initial vowels (with the nasal alternatives), or, we are dealing with an R-S-T-0 root, and thus, 3rd person objects are marked by s-. Four examples of these possibilities are given in (6):12

| (6) | a-i-pota, | a-y-uka, | a-ñ-ami, | a-s-epia |

| 1SG-3O-want | 1SG-*3O-kill | 1SG-3O-squeeze | 1SG-3O-see | |

| ‘I want it’ | ‘I kill it’ | ‘I squeeze it’ | ‘I see it’ |

The decomposition in (6) is only done for the matter of transparency, it is a kind of reconstructed morphology. The analysis of a productive 3rd person marker in all of these cases is a matter of discussion, since the verbs are often understood as units, including the 3rd person marker. This "object marking” is not pronominalizing, i.e. it co-occurs with an explicit 3rd person NP, and it is obligatory, thus rather like a transitivity marker. For this reason, dictionaries, like this one, too, generally list the lexical entries as (i)pota, yuka, ñami, sepia, ‘want, kill, squeeze, see’, respectively. The slot of the 3rd person marker is often replaced by an incorporated noun, which in some cases may also co-occur. Therefore, the dictionary also shows the bare forms, in order to identify the roots.

When only SAPs are interacting in transitive predication, we find the typical Tupi-Guaraní strategy, namely by either marking through the portmanteau prefixes for one direction (1>2), or marking only the 1st or 2nd person by a marker of the che-paradigm, which is then structurally similar to a nominal predication with a possessor. In addition to the pronoun, the predication where 2SG or 2PL are the subject and a 1st person is the object, there is an obligatory emphatic subject pronoun following the verb: eve ‘2>1’.13

We observe a different behaviour of those roots preceded by i-/y-, which do not lose their 3O-prefix in the cases of a higher degree of lexicalization (less lexicalized prefixes are indeed dropped), and those of the R-S-T-0 paradigm, which show the r- forms and 0 for the demonstrated constructions. The verb yuka ‘kill’ (7) does not lose the y-, whereas the verb yako ‘embrace by the neck’ (9) does. Compare the forms in (7) to the ones in (2):| (7) | che yuka, | che yuka eve, | che repia, | che repia eve |

| 1SG kill | 1SG kill 2>1 | 1SG see | 1SG see 2>1 | |

| ‘he/she/they kill(s) me, you kill me, he/she/they see(s) me, you see me’ | ||||

In constructions that require a portmanteau prefix, the initial consonant of the R-S-T-0 forms is dropped, whereas the lexicalized i-/y- remains. Therefore, with an i-/y-initial verb stem, 1>2 and 1PL.excl forms can be homonyms, but with R-S-T-0 stems, they are never (unless the s- also lexicalizes, which still needs to be investigated), as can be observed in (8), where portmanteau oro- ‘2>1’ is contrasted to the forms with the homonymous prefix oro- ‘1PL.excl’:

| (8) | oro-yuka | or | oro-yuka, | but: | oro-epia | and | oro-sepia |

| 1>2-kill | 1PL.excl-kill | ||||||

Verbs that behave like yuka ‘kill’ are thus not listed in the bare form *uka in the dictionary. Other verbs with non-lexicalized i-/y- prefixes, lose them in the same contexts in which the R-S-T-0 roots occur as bare forms (9). For this reason, they can be found twice in the dictionary, too, as a bare root and with the i-/y-prefix. One such example is the verb yako ‘embrace by the neck’, compare to the examples above:

| (9) | a-yako, | che ako, | oro-ako, | oro-yako, | ya-ye-ako | ||

| 1SG-embrace | 1SG embrace | 1>2-embrace | 1PL.excl-embrace | 1PL.incl-RFLX-embrace | |||

| ‘I embrace him/her, he/she embraces me, I embrace you, we embrace him/her, we embrace each other (by the neck)’ | |||||||

Example (9, last word) shows that the initial 3O-marker is also dropped in reflexive derivation with the ye- prefix. Another common context in which the bare form occurs is causative derivation with mbo-/mo-. This prefix applies to intransitive verbs, or it works as a verbalizer on nouns.14

Causative verbs take the active alignment of the a-paradigm. Two examples of causative derivation are given in (10) and (11):| (10) | a-kui, | a-mbo-kui, | che mbo-kui, | oro-mbo-kui, | a-ye-mbo-kui |

| 1SG-fall | 1SG-CAUS-fall | 1SG 1SG-fall | 1>2-CAUS-fall | 1SG-RFLX-CAUS-fall | |

| ‘I fall, I make someone fall, someone makes me fall, I make you fall, I make myself fall’ | |||||

| (11) | che rorɨ, | a-mbo-’orɨ, | che mbo-’orɨ, | oro-mbo-’orɨ, | a-ye-mbo-’orɨ |

| 1SG happy | 1SG-CAUS-happy | 1SG CAUS-happy | 1>2-CAUS-happy | 1SG-RFLX-CAUS-happy | |

| ‘I am happy, I make someone happy, someone makes me happy, I make you happy, I make myself happy’ | |||||

The interaction between the three forms R-S-0 can be observed with the transitive verb apɨ ‘burn’ in (12). No causative can be derived here by mbo-; instead, a causative postposition uka has to be used:

| (12) | a-s-apɨ, | che rapɨ, | a-ye-’apɨ, | a-s-apɨ uka |

| 1SG-3O-burn | 1SG burn | 1SG-RFLX-burn | 1SG-3O-burn CAUS | |

| ‘I burn it, he/she/it burns me, I burn myself, I make him burn it’ | ||||

The slot where the – often lexicalized – 3O prefix occurs, is also a slot where the reflexive ye-, reciprocal yo-, or incorporated nouns enter. Two more prefixes in this position refer to generic objects: mba’e ‘thing or generic non-human object (GNHO)’ and poro- ‘generic human object (GHO)’. Incorporated nouns are very frequently body parts.15 The position of the relational prefix is following the incorporated noun, – po ‘hand’ in (13) –, in case it is the ‘hand’ of someone else than the subject.16 Compare therefore the two examples with the same verb as in (12) and the incorporated noun in (13):

| (13) | S-3O-n-v | S-RFLX-n-v |

| o-i-po-rapɨ, | o-ye-po-’apɨ | |

| 3-3O-hand-burn | 3-RFLX-hand-burn | |

| ‘he/she burns someone’s hand, he/she burns his/her own hand (also PL they)’ | ||

The order of the elements RFLX, CAUS, even 3O markers, depends on their scope and on the (non-)identity of subject, object, and possessors, and much more investigation has to be done on the matter. Compare the following possible orders in Guarayu. Note that some of these phrases were only possible in Hoeller’s times and have lost productivity, or say, another way of expression has won over these constructions.

| (14) | S-CAUS-RFLX-n-v |

| a-mbo-ye-po-’ei | |

| 1SG-CAUS-RFLX-hand-wash | |

| ‘I let him/her wash the hands.’ (Hoeller 1932a:293) not possible anymore today? (transitive verb!) |

| (15) | RFLX-n-CAUS-v |

| a-ñe-akä-mbo-pirer | |

| 1SG-RFLX-head-CAUS-skin | |

| ‘My head is getting bold.’ |

| (16) | S-3O-n-v |

| o-ñ-akä-mombo | |

| 3-3O-head-throw.away | |

| ‘He/She threw somebody’s head.’ |

| (17) | S-3O-n-CAUS-v |

| a-i-pɨ’a-mbo-sɨkɨye | |

| 1SG-3O-heart-CAUS-fear | |

| ‘My heart is frightened.’ |

Especially, incorporation with the noun pɨ’a ‘heart/stomach’ (17) is very common, and it is used for the expression of feelings. These complex predicates are generally considered as being lexicalized. The most often used incorporated form, lexicalized already in the proto-language is ɨ’u ‘drink (lit. water-eat)’.

There are many verbal morphemes in Guarayu. Table 6 lists only the derivational affixes that Guarayu takes for valency changes and which may be part of the lexical entries in the dictionary:

| dictionary form | gloss | description & function |

|---|---|---|

| ye-/ñe- | RFLX | reflexive |

| mbo-/mo- | CAUS | causative of intransitive verbs |

| yo-/ño- | 3O | 3rd person object marker |

| yo-/ño- | RCPC | reciprocal |

| mba’e- | GNHO | generic non-human object, ‘thing’ |

| poro- | GHO | generic human object |

| ro-/no- | CCOM | causative comitative |

Table 6: Guarayu valency-related verbal affixes

Note that one variant of 3O marking is formally identical to reciprocal yo-. In the dictionary, there are a number of forms including this prefix, most of them reciprocal derivations. In addition, these forms have possibly been interpreted as 3O marking by Hoeller, but they are what we know today as the newly developed 3PL marking, which can vary from the longest yuvɨro- via yuvɨ- to only yu-, and this was coexistent with oyu- in Hoeller’s times. The forms given with yu- or you- (in Hoeller

Negation⇫¶

Negation occurs on different levels in Guarayu, and this is, among other things, reflected by various negation particles in the dictionary, some of which are obsolete today. Since negation has not been fully investigated by the time we publish this dictionary, only brief information about the most important type of negation shall be given here. The dictionary contains some entries and examples with morphological negative constructions.

As for morphological negation, the most important characteristic that shall be presented here, is the circumfixal negation in Guarayu on verbal as well as non-verbal predicates. The circumfix in the non-future is a syllable with initial nasal – nd- before vowels, and nda- before consonants, the nasal consonant is pronounced [nd] in an oral environment and [n] in a nasal environment. Usually, no orthographical adaptation to the pronunciation is realized. At the end of the negated word, the suffix -i is attached. A verb of the a-paradigm is thus negated as follows – compare to affirmative in (6):

| (18) | nd-a-i-pota-i, | nd-ere-yuka-i, | nda-ya-ñ-ami, | nd-o-sepia-i |

| NEG-1SG-3O-want-NEG | NEG-2SG-kill-NEG | NEG-1PL.incl-3O-squeeze-NEG | NEG-3-see-NEG | |

| ‘I don’t want it, you didn’t kill it, we don’t squeeze it, he/she doesn’t see it’ | ||||

Circumfixal negation is in particular interesting, because it is a kind of syntactic morphology and it shows the relative boundedness of the pronouns of the che-paradigm. While orthographically the pronouns of the affirmative clause are spelled as separate words, in negative clauses, this is impossible, since the negative affixes are the outmost layer of the whole word and include the bound person markers and possible aspectual or tense suffixes. Compare the examples in (19) with their affirmative counterparts in (3):

| (19) | nda-che-’e-i, | nda-nde-’e-i, | nda-i-’e-i, | nda-yande-’e-i |

| NEG-1SG-eruct-NEG | NEG-2SG-eruct-NEG | NEG-3-eruct-NEGG | NEG-1PL.incl-eruct-NEG | |

| ‘I didn’t eruct, you (SG) didn’t eruct, he/she/ they didn’t eruct, we (incl.) didn’t eruct’ | ||||

There are differences in the future tense, where the circumfix is nda-…-chira, and prohibitive constructions involve additional particles and interact with predicate negation.

Derivation⇫¶

After some valency affecting derivational suffixes have been mentioned in forms of stems and morphology of predicates (and see also Table 6), this section gives a brief overview of nominal derivational affixes that may be part of the lexical entries in the dictionary. One important grammatical characteristic of Tupí-Guaraní languages is that they do not only mark verbal TMA features, but also nominal past, future, potential, and frustrative. While verbal tense does generally not produce lexicalized forms, nominal tense marking can derive terms that become relatively lexicalized in Guarayu. One example of lexicalization is found with nominal past -kwer (nasal and voiced variants ‑(n)gwer). Nouns with this suffix can often have small semantic differences with the unmarked noun, also reflected in the translations. The noun a ‘hair’ refers to a hair on the living body (human or animal). The past form agwer is a hair that is not connected to the body anymore, i.e., a hair we find on the floor, in the soup, or that we use for other purposes (20). Similarly, the soul ä is the one still connected to the living being, but ängwer is the soul that is already unconnected, e.g. after death.

| (20) | s-a-gwer | kui | va’e | (2019: | o-kui | va’e) |

| 3-hair-PAST.N | fall | ATTR | 3.COREF-fall | ATTR | ||

| ‘shed (lit. fallen) wool or feather’ | ||||||

(Hoeller 1932a: 317)

The examples in (21) show the use of nominal tense in Guarayu with the noun rëta ‘house’ (an R-S-T-0 root):

| (21) | s-ëta-gwer, | che | rëta | ramo | che | rëta | rangwer |

| 3-house-PAST.N | 1SG | house | FUT.N | 1SG | house | FRUST.N | |

| ‘his/her former house’ |

(Hoeller 1932a: 337, 217, 218)

Orthography suggests that some of the nominal tense markers are suffixes and others are separate particles, which does not necessarily coincide with their grammatical status of one or the other. See Table 7:

| dictionary form | gloss | description & function |

|---|---|---|

| -kwer, -(n)gwer, -er | PAST.N | nominal past |

| ramo | FUT.N | nominal (perfective) future |

| -rä | FUT.POT | potential future (nominal, possibly also verbal?) |

| rangwer | FRUST.N | nominal frustrative (lit. FUT.POT + PAST.N) |

| -vɨ | POT.N | potential nominalizer ("designated to be”) |

Table 7: Guarayu nominal tense markers

Guarayu has various productive ways of nominalization, which are generally used for adapting a predicate to the context. Nominalization does not necessarily produce a referential term that can be used as an argument, but it also has various other purposes, e.g. different kinds of subordination. The forms of nominalizing suffixes may have had more alternation in Hoeller’s times. Today, some of them are only found in lexicalized words. The most productive nominalizers are given in Table 8:

| dictionary form | gloss | description & function |

|---|---|---|

| va’e | ATTR | attributive nominalizer, nominalizes whole phrases, works for relativization, and is used for attributive adjectives, active participle |

| sar, (-par), -yar | N.AG | agentive nominalizer |

| sa, (-ka), -pa | N.CIRC | circumstantial nominalizer (place, state, instrument) |

| -pɨr (2019:-prɨ), -mbɨr | PPP | passive perfective participle |

| remi-, semi-, temi-, rembi-, sembi-, tembi- | N.PASS | passive participle, nominalizer |

Table 8: Nominalizers in Guarayu

The postponed particle va’e is productively used to derive attributes from either verbs or nouns. The output forms are often translated as adjectives. The particle va’e follows the 3rd person forms of the che-paradigm by default in almost all cases. The following examples show the use of va’e in noun phrases (22) – see also (20) above – and in a clause (23):

| (22) | i-vava | va'e, | tu | va'e, | s-esa-e'ɨ̈ | va'e, | i-po-yevɨ | va'e |

| 3-light | ATTR | father | ATTR | 3-eye-PRIV | ATTR | 3-thread-(re)turn | ATTR | |

| ‘light’ | ‘the ones that have fathers’ | ‘blind’ | ‘twisted thread’ | |||||

(Hoeller 1929: 116, Hoeller 1932a: 39, Hoeller 1929: 106, Hoeller 1932a: 206)

| (23) | a-yapirai | mbɨa | i-gwayɨ | va’e / | i-vava | va’e / | o-vava | va’e17 |

| 1SG-collide | people | 3-play | ATTR | 3-fight | ATTR | 3COREF-fight | ATTR | |

| ‘I bumped into people that were playing / fighting’ | ||||||||

(Hoeller 1932a: 23, 280)

Other nominalizers can be applied productively to almost any verb (cf. also Hoeller 1932b); examples (24) and (25) demonstrate this:

| (24) | a-yamotare'ɨ̈, | yamotare'ɨ̈-sar, | yamotare'ɨ̈-mbɨr |

| 1SG-dislike | dislike-N.AG | dislike-PPP | |

| ‘I dislike someone’ | ‘the hater (the one who dislikes)’ | ‘the enemy (the one who is disliked)’ |

(Hoeller 1932a: 277)

| (25) | a-mbo’e, | temi-mbo’e, | ye-mbo'e-sa, | poro-mbo'e-sar |

| 1SG-study | N.PASS-study | RFLX-study-N.CIRC | GHO-study-N.AG | |

| ‘I study’ | ‘student’ | ‘the study’ | ‘teacher’ | |

| (the one who is made study) | (the action of studying) | (the one who teaches people) |

(Hoeller 1932a: 118, 244; Hoeller 1929: 126, 85)

Constituent order and postpositions⇫¶

Since investigation on this topic is still missing, we cannot give information regarding constituent order. As for the position of explicit subject and object NPs, more systematic investigation has to be undertaken, especially in order to describe the development away from an OV order during the past century. What shall be addressed in this section are the ubiquitousness of postpositions and the order of elements in the two types of compounds.

Everything that was shown about objects above (forms of stems and morphology of predicates) only accounts for direct objects. However, depending on the semantic role the verb coincides with, many participants are also expressed as oblique objects. These obliques are marked by postpositions. We could locate the postpositions on a continuum of grammaticality. However, much more investigation of the synchronic data and comparative development has to be done in order to present this continuum of postpositions.<a href="#ref18" data-toggle="tooltip" id="18" title="It seems that a tentative continuum of grammaticality could be: DAT < CIRC < LOC/SEP/INSTR < others.">18

The most common or most grammaticalized postposition, the dative, is irregular. SAP mark the dative on the pronouns by adding the suffix -u – cheu, ndeu, yandeu, oreu, peu (compare che-paradigm in Table 4). In the 3rd person, there is a pronominal dative chupe with unproductive 3rd person marking *ch-,19 whereas the dative on nouns is marked by the postposition upe. A verb like porandu ‘ask’ is e.g. one that takes dative objects:| (26) | a-porandu | nde-u | or | o-porandu | chupe, | but not: | *oro-porandu, | or | *o-i-porandu |

| 1SG-ask | 2SG-DAT | 3-ask | 3.DAT | 1>2-ask | 3-3O-ask | ||||

| ‘I ask you’ | ‘he/she asks him/her’ | (I ask you) | (he/she asks him/her) | ||||||

Postpositions also inflect for person (compare the description of predication in forms of stems and morphology of predicates), so that it is not surprising to find deviating forms for the 3rd person, like e.g. sui (SAP)/ichui (3) ‘separative (from)’ (compare to sɨ ‘mother’ and ichɨ ‘his/her mother’, cf. end of Guarayu phonology and morphophonology). Other postpositions are similar to nouns of the R-S-(T-)0 class, such as rese/sese ‘circumstantial (about)’, renonde/senonde/tenonde ‘in front of’ (with the full R-S-T-0 paradigm still found in Hoeller), rupi/(supi-)20 ‘locative plural (along, by, across)’. These postpositions are in fact non-verbal predications in Guarayu, and therefore they can be found in different forms and constructions, similar to the nominal roots.

| (27) | a-ma’ë | nde | rese | (28) | a-ye-pɨtaso | nde | sui | ||

| 1SG-look | 2SG | CIRC |

Another group of postpositions is unchangeable: locative -pe (old form), -ve (changes only phonologically due to the nasality of a preceding syllable or word in Hoeller 1932a, b: pe, ve, me) and pɨpe ‘inside, stative locative (LOC.ST), instrumental (INSTR)’.21 The use of -ve ‘LOC’ and pɨpe ‘LOC.ST/INSTR’ is illustrated in (29) and (30):

| (29) | che | rëta-ve | teiete. |

| 1SG | house-LOC | self.same | |

| ‘in my own house’ | |||

(Hoeller 1932: 222)

| (30) | oro-ye-karo | pɨpe | oro-karu | (2019: | ore | karo | pɨpe | oro-karu) |

| 1PL.excl-RFLX-eat | LOC.ST | 1PL.excl-eat | 1PL.excl | eat | LOC.ST | 1PL.excl-eat | ||

| ‘We eat from the same pot.’ | ||||||||

(Hoeller 1932: 48)

The postposition pɨpe can sometimes also alternate with other oblique postpositions, as can be observed in (32), in contrast to (31), where the roles are determined:

| (31) | a-kwa | sese | ɨvɨra | pɨpe. |

| 1SG-hit | 3.CIRC | stick | INSTR | |

| ‘I hit him/her with a stick.’ | ||||

(Hoeller 1932: 55)

| (32) | a-mondo | yukɨr | (2019: yukrɨ) | i-pɨpe / | sese22 |

| 1SG-put | salt | 3-LOC.ST | 3.CIRC | ||

| ‘I salt it.’ | |||||

(Hoeller 1932: 312)

Some postpositions have slightly changed their forms today. We also observe small semantic changes from Hoeller’s times till today. Finally, most interesting may be the change of grammaticalized postposition related to specific verbs, which means a change in perception of the semantic roles of the oblique participants. This is a promising topic for future investigation, since the semantic roles of obliques have been documented well in Hoeller (1932b). We have not systematically entered information about semantic roles, but where there was a note on this topic by Hoeller, we included it in the paradigm field.

Compounding is very productive in Guarayu, and it concerns mostly the combination of two, but never more than three roots. Interestingly, both orders can be detected, a modifying root in first or second position. Lexicalized ("morphological”) compounds are often spelled as one word, and they take the bare roots in the second position – cf. example (33). Other structural compound constructions can be analysed as syntactic compounds with a relational element in the second position.

Compounds are commonly found with body part nouns, such as pokupe ‘back of the hand’ < po ‘hand’ and kupe ‘back’, or äprɨ ‘tip of the nose’ < ä ‘nose’ and -prɨ ‘pointed end’. Compounding with colour terms is common, too: ayu ‘white hair’ < a ‘hair’ and yu ‘yellow’.23 Animal and plant names frequently consist of compounds, in these cases the terms are usually descriptive. Animal body parts and plant parts are also expressed as compounds. Examples of morphological compounds with two nominal roots are given in (33) – note that the decomposition is only presented here for the matter of transparency; the words are in tendency lexicalized:

| (33) | sevo'ipe, | mbagwarichï, | vɨrachimbe, | ka'a aimbe, | amba'ɨvirer | |

| sevo’i-pe | mbagwari-chï | vɨra-chï-mbe | ka’a | aimbe | amba-’ɨ-virer | |

| worm-flat | heron-white | bird-beak-flat | plant | sharp | ambaibo-tree-bark | |

| ‘leech’ | ‘white heron’ | ‘spoonbill’ | ‘chaáco tree’ | ‘bark of the ambaibo tree’ | ||

Examples of compounds with the mentioned relational forms (apart from incorporation, shown in forms of stems and morphology of predicates) in the second position are frequent and just as frequently lexicalized. The reason for calling this syntactic compounds rather than morphological compounds is that the relational consonant is the marker of an actual predication (cf. forms of stems and morphology of predicates). In fact, for non-relational roots, it may not be possible to distinguish the two types of compounds. Consider (34) with some examples of such compounds, and note that mba’e ‘thing (GNHO)’ is a productive noun in these constructions to refer to things and animals, also functioning as an (instrumental) nominalizer:24

| (34) | mba’e | ro’o | mba’e-räro | mberɨ-ro | arɨ | retɨma |

| thing | meat | thing-take | plantain-leaf | sun | leg | |

| ‘meat’ | ‘hunting’ | ‘plantain leaf’ | ‘sun beam’ | |||

The classification of compounds as relational predicates or not can also change over time, so that we may find two possibilities co-occurring, as in (35), which are both given as alternatives in Hoeller (1932a) and today, the relational form has won over the other:

| (35) | mba’e asɨ | or | mba’e rasɨ |

| thing hurt | thing hurt | ||

| ‘pain, illness’ | ‘pain, illness’ |

Compounding of pɨ’a ‘heart’ with verb roots has been addressed under the topic of incorporation in forms of stems and morphology of predicates. Furthermore, apart from nouns, also two verbal roots can compose as one complex verb. This needs to be investigated much more, but generally the more specific verb comes in first, and that of a more general verb in the second position. Verbs that frequently form compounds are pota ‘want’, katu ‘can’, (ye)vɨ ‘return’. Many combinations have lexicalized – e.g. yepota ‘arrive’ < yu ‘come’ and pota ‘want’ –, and the verbs pota ‘want’ and katu ‘can’ have even grammaticalized into a desiderative and potential suffix, respectively (already in Hoeller’s times). Some verbal compounds are given in (36) and (37):

| (36) | a-mombe’u | yevɨ, | a-ikove | yevɨ, | aiko | asɨ |

| 1SG-tell | return | 1SG-live | return | 1SG-live | pain | |

| ‘I repeat what was said’ | ‘I revive’ | ‘I live in misery (suffer)’ | ||||

(Hoeller 1932a:290, 89)

| (37) | a-ñe-ra-pü’ä |

| 1SG-RFLX-put.down-get.up | |

| ‘I get up from bed (after an illness)’ |

Not only the fact that many examples of the compounds are given as two separate words in Hoeller and by Guarayu speakers today, illustrates the transparency of the constructions. We need to investigate much more, taking morphological processes, like negation, into account, in order to classify these syntactic co-occurrences as actual compounds, or possibly rather other constructions. It is also possible that after a second deep look, the first lexical root turns out to be nominal throughout, and thus the whole is better called incorporation.

Cultural notes⇫¶

In this section, we address a few important cultural issues interacting with the Guarayu language or relevant for reading the dictionary. This includes some notes on the complex kinship system, gender differences, and some general cultural issues, especially regarding Guarayu mythology.

Guarayu kinship terminology⇫¶

There are various subdivisions in the Guarayu kinship system, based on gender of the referent, the relational referent and relative age of the referents. In addition, there are certain vocative forms and nicknames that are used by SAP that differ from the relational terms used for 3rd persons. The generations usually counted today range from G+2 to G-2, even though Hoeller (1932a) proposes terms for the generation G+3 – tamoï yoapɨ ‘great-grandfather (lit. multiplied grandfather)’. Terms like this cannot be confirmed by the oldest of our consultants and may have been innovations by the priests that did not conventionalize. It is rather notable that a certain circular understanding is expressed by the fact that the word yari ‘grandmother’ (yarɨ in Hoeller 1932a) can also be used as a nickname for the granddaughter (by parents and grandparents, possibly also by any other woman).25 Grandparents are distinguished by their own gender, but grandchildren are not; in this case the gender of the related referent is relevant. Thus, the grandmother uses a different term for the grandchildren than the grandfather. In the Guarayu kinship system, the father’s brother and the mother’s sister are conceived as the same, which also has effects for referring to their descendants. This was presumably related to marriage rules for cross-cousins. Children of woman are not distinguished by gender, whereas the children of men are. There is no distinct expression for first born or for age differences. The vocative terms for father differ by gender of the related referent, namely men use the Guarayu term che ru ‘my father’, but women the Spanish loanword papa ‘father’, interestingly already in Hoeller’s times. The siblings for women and men are likewise distinguished into different gender and age relations (older and younger), which is partly expressed in vocative terms, as well. Many of the nicknames brothers and sisters used for another in Hoeller’s times are obsolete today, like e.g. chi’ä, a name women give their younger siblings, or also mothers and other women to little girls, derived from che ä ‘my soul’. The complete Guarayu kinship system needs to be investigated further, so we only address some general patterns here. The notable interaction with social kinship is an additional complication in Guarayu. If e.g. your father is given the nickname of a certain kinship relation by someone who may not even be directly related by consanguinity, say he is addressed as ‘my father’ – vocative as well as descriptive terms can be used –, then you automatically regard this person as an older or younger brother or sister, accordingly. Or if someone calls your father ‘his son’, you address the person ‘your grandfather’, irrespective of his age. The translations given in this dictionary were elaborated with the Guarayu speakers and also contain Hoeller’s information. The information of "gender” given in this dictionary does not necessarily refer to the speaker’s gender – as often assumed – but in fact to the gender of the related referent, so a sister of a woman is marked as "FEM” in the field of genderlect information, however, this does not mean that only women can use this word, except for the vocative terms. In the Guarayu language classes for officials, the Guarayu teachers have a hard time explaining the kinship terms and simplify this by stating that there is a women’s and a men’s speech. This is not strictly true for all of those terms.

Guarayu genderlect⇫¶

Despite the fact that genderlect does not count for most of the variations in kinship terminology (see Guarayu kinship terminology), there is a genderlect difference in Guarayu. Genderlect is notable in a high number of interjections, which even differ in the local dialects. Only a few of them are listed in Hoeller’s dictionary. Words that are close to interjections, such as the reply ‘yes’ and ‘yes indeed’, show a speaker gender difference: while men say taa, women use jëjë ‘yes’ and ere ‘yes indeed’. Even though Hoeller (1932a: 232) remarks that the male form were increasingly used by women, this cannot be confirmed by our investigation.

A phonological genderlect difference, still argued for by Hoeller (1932b), that can only be tentatively confirmed by current data is the different degree of affrication of the consonant <s> or /ts/, pronounced as [s] by women and [ts] by men. The preferred way of pronunciation today is the affricate [ts] by both, men and women. This characteristic is so strong that also men and women transfer it to the pronunciation of the s in Spanish as [ts]. According to Hoeller, this was the masculine variation:

z [/ts/; today <s>] This [sound] does not cause any difficulties, but it is very soft, so that we often only hear s. Zìrì [Sɨrɨ], the chonta palm. The name for the Sirionó Indians may have been derived from this word, a sign that the Carai [Europeans] heard the z as a soft sound.

Note. It shall be mentioned for the matter of curiosity that the women and girls pronounce the z as s or ss, while the men have the z-sound [[ts]]. Ozo [[oso]], he went away, is pronounced otso or odso by the men, by women as osso. (Hoeller 1932b: 2, our translation and emphasis)26

This phonological gender difference cannot be perceived anymore systematically today (2019). However, women may sometimes pronounce the sound with a little bit less affrication in conversation with men. Hoeller (1929, 1932a) does not make any distinction in his dictionary.

Guarayu mythology⇫¶

The Guarayu mythology is in great part similar to Guaraní mythology (as described in e.g. Chamorro 2004), and it can also be compared to the better described Guarasu mythology (Riester 1972). There are various layers of religious authorities that played a role in the creation of the world, the animals, and humanity and the world order of the elements. The information about the creation and the first mythological personalities is mostly derived from Cors’ notes (Cors [1875] in Mendoza 1957: 109f), and even though the Guarayu are talking about these original powers, it is unclear, how much interference with the priests’ early interpretation there is nowadays (Villalta 2018). Before the world was created, there was a mythological being, the Sagwagwayu, but his role is unclear, because he does not seem to have been a creator. He is reported for being an envious person, who got jealous of the creator of the world, because Sagwagwayu had come first and the world’s creator after him. The original creator of the world seems to have been a water worm mbir that transformed himself into a person: Mbirakucha.27 Apart from him, there were two other ramoi ‘grandfather’ (tamoï in Hoeller 1932a), which is how they are addressed, and they all took their part in creating the world and the people. The Mbirakucha is in fact the ramoi of the Brazilians, the ramoi of the Guarayu is Ava angui, and Kangir is the ramoi of the Black people. The spirits of the ramoi dwell on the ɨvɨtrɨ rusu ‘Cerro Grande (big mountain), in Santa María on the way from Ascensión to San Pablo. This is a sacred place for the Guarayu, and it is said to save people in times of natural catastrophes. They also believe that on the ɨvɨtrɨ rusu, ramoi lives with his wife, yari ‘grandmother’ (yarɨ in Hoeller 1932a). The top of the ɨvɨtrɨ rusu can only be reached after a purification process, a special and traditional way of washing. The word ramoi stands for the antecedents of the Guarayu, when talking about the ɨvɨtrɨ rusu. However, ramoi also refers to the God of the Guarayo, which is Ava angui (cf. Urañavi 2009). Ava angui does not live on earth anymore, he went to a place behind the sun, where he is producing his own light. When the Guarayo die, they go back to the ramoi, but only after passing a long path of tests. The kin terminology for the Guarayo God also shows an additional interaction between kinship on the mythological basis and today’s biological kinship relations.

Other plants, animals and natural phenomena have been created in the course of younger mythological history, such as the twin myth and many others.

The word tüpa (or Guaraní Tupã, cf. Chamorro 2004: 123) was chosen for the concept of the singular Christian God in early times of contact with Guaraní peoples, at the end of the 16th century. Even non-Guaraní languages have borrowed this word in the course of Christianisation, e.g. the Chiquitano, who have learnt this word from the Jesuits. The Guarayu also use this term in church: tüpa. The ramoi (tamoï) is the Guarayu God.

Today, the Guarayo pray to the ramoi, meaning tüpa, namely the Catholic God. The identification of the two terms probably started in the times of Cors (19th century) already, but it has not completed fully yet. Many personalities are still remembered by the Guarayo, but others have been forgotten. In Hoeller’s dictionary, we find much more of this knowledge still contained. Hoeller also gives names for certain star constellations, not all confirmed today. These constellations express a relation between the mythological world and the real world. We are grateful to have some of these terms recorded in the dictionary.