Nen dictionary

Contributors⇫¶

Many members of the Nen-speaking community have contributed to the compilation of this dictionary, including:

It additionally reflects the work of the Äkämär Zidbn Ogiabs (Nen Language Committee) whose office-bearer ins 2014-2017 were Goe Dibod (Chairman), Joseph Teräb Blag (Vie Chairman), Daniel Gvae (Secretary)), Yosang Amto (Treasurer), Geroma Rami and Ymta Sobae (Security 2015), Daniel Gbae (Security 2016-2017), Ebram Bamaga and Yaga Wlila (Community Liaison), as well as the clan committees of the Bangu, Erboag, Kiémbtuwirer, Nängblag, Sangara and Seregu groups who helped in the interviewing of a wide range of speakers during 2014-2018, and whose names are listed above.

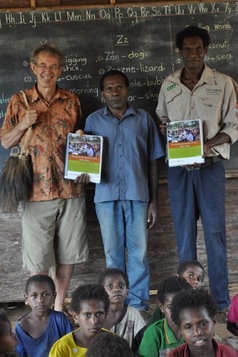

Photo 1: Nen language workers with draft dictionary, July 2017, Bimadbn Community Centre

Photo 2: Nen literacy class, Bimadbn Elementary School, September 2018

Photo 3: Bimadbn Elementary School Teachers Songa Dibod (left) and Bernda Aramang (right) with Nick Evans, September 2018

Further assistance has come from Kipiro Damas (botanical identifications), Chris Healey (bird identifications, as well as an enormous amount of work obtaining bird photos and recordings of bird calls); both Kipiro and Chris participated in two field trips thanks to support from a Volkswagenstiftung DoBeS grant.

Photo 4: Kipiro Damas identifying plants with Gvae Néwir and Jimmy Nébni

Photo 5: Chris Healey in a bird hide in bush just south of Bimadbn

In addition, many further insights came from the participation of Penny Johnson (anthropology), who participated in eight joint field trips, Julia Miller (sociophonetics), who participated in four, and Darja Hoenigma (anthropology), who participated in one.

The language and its speakers⇫¶

Nen is a language spoken in the Morehead District of Western Province, Papua New Guinea. It is not to be confused with another language of the same name, the Southern Bantoid Nen of Cameroon. Around 400 people speak the language. Most live in the village of Bimadbn (also spelled Bimadeben), but as a result of intermarriage with neighbouring groups many speakers are to be found in neighbouring villages, particularly Dimsisi (to the east – dominant language Idi) and Govav (Gopap in Nen, Gubam in map spellings) to the west. A few dozen speakers reside in the provincial capital, Daru, and the national capital, Port Moresby.

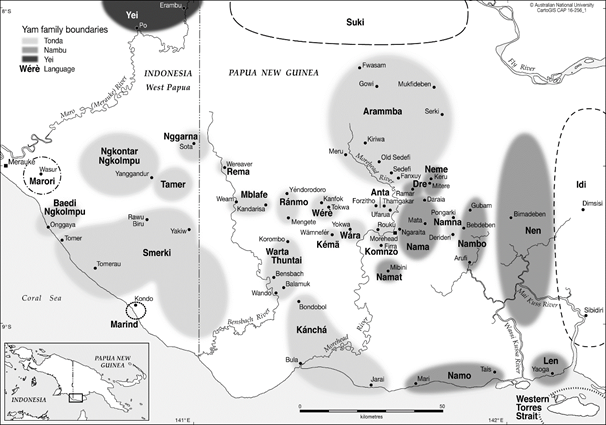

The language name Nen is the word for ‘what’, based on a standard practice in Southern New Guinea of naming languages after their word for ‘what’ (Evans 2012a). Other names used for the language are Nen zi ‘Nen language’, Nen ym ‘what is it?’ and Äkämär zi ‘Äkämär language’, where Äkämär is the name of the tribe associated with the Nen language. (An important early ethnography of the region, Williams (1936:30), transcribes the tribal name as Wekamara). Nen belongs to the Nambu branch of the language family known as Yam (Evans 2009, Evans et al 2018), or Morehead-Wasur (Glottolog). Earlier classifications, such as Ross (2005), included the Yam languages plus the Pahoturi River and Eastern Trans-Fly languages in a larger family, Trans-Fly, but the evidence for that larger unit is weak.

The village of Bimadbn itself, with a population of around 350, is highly multilingual, with over ten languages present, and most individuals living there speak two or more languages fluently, with a typical portfolio of local languages being Nen, Nmbo and Idi. In earlier times the dominant lingua franca was Hiri Motu, still known by people of middle age or above. Today English is the dominant outside language, but it will normallyonly be used with people from outside the immediate district – with those from the Morehead district the use of local languages would be normal, even if the conversation proceeds in an asymmetric way (e.g. one person speaking Nen and the other replying in Nmbo). Tok Pisin is beginning to appear in limited domains, such as church dealings, joking, and interactions with Papua New Guineans from further afield. All children growing up in the village learn Nen fluently and, apart from its small speaker base, the language is currently quite secure – the statement in Glottolog that it is ‘definitively endangered’ is completely off the mark. In principle it is used, in a transitional way, in the Elementary School, alongside English, but the lack of written materials and general problems with the schooling system mean that children receive little formal exposure to it, though their teachers mainly use Nen (with some English) in talking to them in Elementary School. Subsequent schooling in the village nominally takes place in English, partly because some of the teachers come from elsewhere (e.g. the Sepik) and a number of children from other villages and languages board in the village for their post-elementary education up to Year 8.

Literacy in the language is limited to a few individuals – and literacy in general is rather limited, with many people unable to read and write at all, and others primarily limited in their literacy skills to reading well-known passages from the Bible, sending text messages by phone, or reading noticeboards. When I began work on the language in 2008 there was a provisional orthography designed by the SIL linguists Marco and René Boevé, who had primarily been working on Arammba, a distantly related Yam language of the Tonda branch. I was shown a small reader with a few words illustrating each letter or letter combination. Words written with this orthography were also written on blackboards in the Elementary School. Over the next two years this orthography was revised somewhat (see below) and has since stabilised to that used here. Following community request, some portions of the Bible have now been translated into Nen, and at Sunday services readings from these portions of the Nen Bible are carried out. Around ten people have sufficient literacy skills to do this, based on solid rehearsal of the reading passages. A smaller number, such as Jimmy Nébni, Nébni Mkao and Goe Dibod, who have been intimately involved in language work and transcription, have a more confident command of the writing system, including the ability to transcribe accurately using ELAN in Jimmy Nébni’s case. It is hoped that the availability of this dictionary in a form that can be accessed by the Nen diaspora will help promote literacy skills. The link will be announced through Facebook, which is gaining in popularity among Nen speakers.

Map: Languages of the Yam family.

There are around twenty-five languages in the Yam family, depending how one draws the boundary between language and dialect. So far there is no dictionary of any Yam language (though Siegel has a forthcoming dictionary of Nama). Recent work on the languages of this family has resulted in dissertation grammars of Komnzo (Döhler 2016, revised version published as Döhler 2018), Ngkolmpu (Carroll 2017), dissertation treatments of more specific topics such as split intransitivity in Ranmo (Lee 2016) and sociolinguistic variation in Nmbo (Kashima in prep.), a detailed survey article of the languages of Southern New Guinea that includes nearly 40 pages on the Yam languages (Evans et al 2018:678-697, 744-761), and a number of articles on grammatical issues including Siegel (2014) on Nama tense and aspect, and Evans (2009, 2012b, 2014, 2015a,b, 2017) and Evans & Miller (2016) on various aspects of Nen. Before I began my fieldwork on Nen in 2008 there was next to no documentation on the language, aside from the brief spelling guide by Boevé & Boevé (2000) and some brief and inaccurate word lists compiled around the opening decades of the twentieth century (see Evans et al 2018:683-4 for references and evaluation of the transcriptions against modern Nen forms). There was somewhat better documentation of the anthropology of the region just to the west (with peripheral mentions of Nen), including the classic ethnography by Williams (1936) of the Nmbo-speaking Keraki tribe immediately to the west of Nen, the insightful PhD thesis on social structure and relations to land among the people of Rouku, by Ayres (1983), who incidentally was the first to make sound recordings of Nen speakers1.

Source of the data⇫¶

All material in this dictionary was collected by the primary author during annual fieldtrips between 2008 and 2018, totalling approximately ten months. The vast bulk was recorded in Bimadbn village itself, but additional material was collected in surrounding garden hamlets (e.g. Zeri), neighbouring villages (e.g. Govav, Dimsisi), the small local centre known as Morehead Station, in the provincial capital of Daru, and during travel by dinghy, bicycle, on foot and (occasionally) in the back of a truck between these locations.

The dictionary remains provisional and incomplete but this version is being published so as to provide a resource for community members, and scholars from a range of backgrounds, wanting to learn something about the vocabulary of this fascinating language.

Over the eleven years of fieldwork, different emphases, reflecting different patterns of project funding, led to the elaboration of particular parts of the dictionary. After two years’ initial support from a Professorial setup grant at the Australian National University, I received outside grant funding between 2010 and 2015 from two further agencies, the Australian Research Council (Grant: Languages of Southern New Guinea) and the DoBeS Program (Dokumentation bedrohter Sprachen) of the Volkswagenstiftung. The focus of the first of these was on building up descriptive materials on Nen and related languages; working in a team with linguists working on other languages of Southern New Guinea (Jeff Siegel on Nama, Christian Döhler on Komnzo, Wayan Arka on Marori and Matt Carroll on Ngkolmpu) meant that many ideas about likely lexicalisations were passed back and forth, opening up detailed lines of enquiry. The second on wide-ranging naturalistic documentation with particular focus on ethnobotany (drawing on the botanical expertise of Kipiro Damas of the PNG National Herbarium) and ethnoornithology (drawing on the deep knowledge of birds and ethnobiology of another project participant, Dr Chris Healey. Particularly from the inception of the DoBeS project, and thanks to the extra participation of Julia Miller, the Nen documentation project began building a collection of audio and video files illustrating a wide variety of traditional activities and aspects of modern life. Initially these were archived in the DoBeS archive but more recently all Nen media files and transcriptions have started being lodged in the Digital Archive Paradisec. I also investigated Nen valency patterns in detail as part of the Leipzig Valency Classes Project, using a questionnaire developed by Andrej Malchukov, Iren Hartmann, Martin Haspelmath, Bernard Comrie and Søren Wichmann. Since 2014 my fieldtrips have been supported by the Australian Research Council Laureate Project ‘Wellsprings of Linguistic Diversity’, which focuses on variation in small-scale speech communities – at this point recordings began to be made across a much wider range of speakers, mostly through interviews by Nen speakers. It must be emphasised that all of the above activities have generated a vast collection of recordings, of which only a small part has been transcribed (so far around 30,000 words), and even within that corpus not all words or usages have been incorporated into this dictionary.

Apart from the changing foci mentioned above, a wide range of techniques have been used to extend and refine the vocabulary recorded here: elicitation of word lists as an initial method, collection of plant specimens (with Kipiro Damas) and identification of birds from sightings and calls (with Chris Healey), excerpting of vocabulary from recorded materials and transcriptions, talking about the physical and social environment as we moved through it on visits to yam gardens, hamlets and special sites, and most importantly simple participant observation as Nen people have tried to teach me the intricacies of their language. As befits a multilingual society where it is normal for people to be regularly learning new languages, Nen speakers have clear ideas about how this should be done, such as whispering in my ear what to say in answer to an anticipated question or command. In addition to that, many words arose during focussed discussions during sessions held most Sunday afternoons as part of my compact with the community to help them with their ambition of translating the Bible into Nen.

A word on neologisms: Nen speakers have an ideology that basically everything should be describable using the resources of the Nen language (notwithstanding a few loanwords), and see nothing amiss with adding in new coinages of various types, including botanical terms (when nobody could recall a term for a plant species they all agreed was distinct from another known by the same name), terms for professions (e.g. wawapser for ‘teacher’, based on the verb wawaps ‘to teach’), and terms for the institutions and techniques of the modern world, e.g. sarnḡ ‘yamhouse’ gets extended to ‘bank’, and sode ‘pile’ (also pronounced file in local English) gets extended to mean a file on a computer. Nen, like English or German, is a living language, and in line with community wishes such new coinages have been included in this dictionary.

Every year since 2010 I have produced an annual ‘dictionary harvest’, a printout of the provisional dictionary so far, and taken up some printouts on my field trip. During the field trip these would be passed around and annotated by a range of interested people such as Jimmy Nébni, Goe Dibod and Nébni Mkao, who would often borrow them overnight and read and mark them up by torchlight. (There is no power in the village). The efforts of these Nen lexicographers have done a great deal to render this more accurate than it would otherwise have been, though many mistakes undoubtedly remain to be resolved. Others such as Grmbo Blba, more interested in grammatical structures, would join me on my veranda after dark, taking me through notebooks they had filled with interesting homophones or similar-sounding words.

An indication of the community’s interest in this dictionary project comes from its enthusiasm in keeping track of the steady growth in the number of entries (and its commitment to help keep this expanding). In 2011 a large tree was cut down from the nearby forest and squared up to form a ‘dictionary pole’, erected in front of my house in the village. Each field trip the number of lexical entries recorded up to the previous year is carved into the side of the pole. Villagers take great pride in drawing this pole to the attention of visitors from other villages. As well as recording the number using Arabic numerals, the number of entries is also recorded using the Nen senary (base six) system (Evans 2009, and see below under specialties of vocabulary). To avoid confusion in how to interpret the digits – for example should 1000 be interpreted as one thousand or as 216 (six cubed), those to be interpreted as base six are written using the Devanagari numerals. For example, the interim number of dictionary entries recorded to 2010 – i.e. 2327, when written as a power of 6, is 2327 = 1 x 1296 (1 x 64 ) + 4 x 216 (4 x 63 ) + 4 x 36 (4 x 62 ) + 2 x 6 + 1. This was written as shown on the dictionary pole.

Photo 6: The dictionary pole. Left: Jimmy Nébni with the author marking out the year’s numbers for carving on the pole. Right: close-up of the entry record for 2010, showing the number of entries (2327), expressed in the Nen base-six numeral system using Devanagari numerals.

The orthography (writing system) and pronunciation⇫¶

The writing system used in this dictionary is a practical orthography, developed by the author in consultation with the Nen speech community on the basis of an earlier orthography suggested by Boevé and Boevé (2000), with some modifications to be mentioned below. Apart from prenasalised obstruents, which are written with a nasal letter plus an obstruent, e.g. mb, nd, nz, all phonemes are represented by a single letter (grapheme) in the practical orthography, though there are a number of diacritics. See Evans & Miller (2016) for a detailed treatment of Nen phonetics.

Table 1 shows the inventory of consonants, using both phonetic letters and (in square brackets) the graphemes of the practical writing system. Apart from <nz> and <z>, each of which allows a number of equally-accepted pronunciations, consonants do not exhibit significant variation in their pronunciation. Of particular note is the labial-velar series, where e.g. a k and p are produced at the same time (as in West African languages like Igbo).2 The h phoneme is marginal and found only in a few interactive words (like ahã ‘here you are!’) and some English loan words like hedmasta ‘headmaster’ or hos ‘horse’, though in such words many speakers drop the h and pronounce them as edmasta or os.

| Bilabial | Alveolar / dental | Palatal | Velar | Labial-velar | Glottal | |

| Voiceless stop | p <p> | ṱ <t> | k <k> | k͡bw <q> | ||

| Voiced stop | b <b> | d <d> | g <g> | g͡b <ḡ> | ||

| Prenasalised stop | mb <mb> | nd <nd> | ŋg <ng> | ŋg͡bw <nḡ> | ||

| Prenasalised affricate | nz <nz> ([nz ~ ndz~ ndʒ ]) |

|||||

| Nasal | m <m> | n <n> | ɲ <ñ> | |||

| Voiced Affricate | dʒ <z> ([z ~ dz ~ dʒ]) |

|||||

| Voiceless fricative | s <s> | h <h> | ||||

| Lateral | l <l> | |||||

| Trill | r <r> | |||||

| Semi-vowel | j <y> | w <w> |

Table 1. Consonant phonemes (//) and their corresponding graphemes (< >) in the Nen orthography; significant allophones shown in [] where they deviate from the IPA symbol for the phoneme

With regard to vowels, there are six main full vowels, plus two short vowels, as well as two nasalised vowels with very marginal status (each confined to a few interactional words like gẽhẽ ‘over there’, ẽ ‘yes’ and ahã ‘here you are!’). These are shown in Table 2:

| Front | Back | |||

| Non-short | Short | (Short) | Non-short | |

| High | i <i> | ɩ <é> | u <u> | |

| Mid | e <e> ẽ <ẽ> | ə <á> | o <o> | |

| Low | æ ~ ɛ <ä> | a <a>, ã <ã> | ||

Table 2. Vowel phonemes (//) and their corresponding graphemes (< >). Note that most of the time the ə is predictable and is not written (see below).

Short vowels have a complex phonology. <é> (/ɩ/) is short and lower and more central than /i/, though articulated more tensely than the IPA symbol would normally suggest. It can neither begin nor end a word, though it can begin a root (e.g. -égérngr ‘be away (non-dual)’, as in yégérngr /jɩgɩrŋgr/ ‘(s)he is away’, where y- is the third person subject prefix. When flanked by a consonantal onset and nucleus it contrasts phonemically with other vowels – as shown by minimal pairs contrasting it with /e/ and /i/, as well as with syllabic /r/:

A voiceless “echo” version of this vowel is common after monosyllabic stems in which the vowel occurs, if they end in a voiced stop, e.g.

/ə/ ( [ə] ~ [ɐ]) is the most complex vowel analytically. In most cases phonetic schwa results from epenthesis and is not phonemic– essentially phonetic schwa is used to fill in the nuclei of syllables to which no vocalic or liquid segment is linked, e.g.

To help readers insert this vowel correctly – particularly given the long strings of consonants the reader will be puzzled to encounter in this dictionary – here are the rules governing schwa epenthesis:

- Associate each specified vowel with a syllable nucleus.

- In word-final position, and some other final positions (of reduplicate elements, compounds, verb stems, and boundaries before case affixes) associate the last consonant with a coda position.

- For the remaining segments in the word, maximize onsets, in other words associate as many consonants as possible are associated with onset position. Exception: the clusters /Sr/, /Sl/, /NSr/ (where S is a stop, and NS a prenasalised stop), /sp/ and /sk/ are syllabified as complex onsets before following associated vowels, e.g. <spélnḡ> [spɪlɪŋg͡bw] ‘basket’, <skop> [skop] ‘eye’, <drondro> [drondro] ‘night carpenter bird’.

- Associate any unassociated liquid segments (r or l) which directly follow consonants to nucleus slots.

- Likewise reassociate the nasal element of any NS cluster that is not in word-initial position to the preceding coda.

- Fill any unassociated nucleus slots with an epenthetic [ə]. If the immediately preceding vowel is /ɩ/, make the epenthetic vowel [ɩ] instead of [ə].

These principles can be illustrated with the following examples: <kanam> /kanam/ ‘snake’ > [ka.nam] <knm> /knm/ ‘come!’ > [kə.nəm ~ kə.nṃ] <nnam> /nnam/ ‘come (later)!’ > [nə.nam] <argban> /argban/ ‘Tree species: Acacia mangium’ > [a.rə.gə.ban] <Kokottkape> /Kokottkape/ ‘place name’ > [kokotətəkape] <wañmst> waɲm-s-t/ ‘to close’ /waɲm-s-t/> [wa.ñəm.sət ~ wa.ñṃ.sət] <sakrdbnmne> /sakrdbnmne/ ‘from the trunk of the sakr palm’ > (sakr-dbn-mne [palm-stem-ORG] [sa.kr.dəbən.məne ~ sa.kr.dəbṇ.məne]) <kr> /kr/ ‘death, dead’ > [kr̩]

Main features of the Nen language⇫¶

We do not include a sketch grammar here, since a full grammar of Nen is in preparation. Rather, this section is intended to give the reader enough understanding of the language to understand the structuring of the dictionary. A better understanding can be gained from the following articles or chapters dealing with specific aspects of the language: Evans (2014) on positional verbs, Evans (2015a) on valency, Evans (2015b) on inflection, Evans (2017) on quantifiers, Evans (2019) on the complex four-valued number system, and the sketch on pp. 685-690 of Evans et al (2017) for a somewhat more detailed overview than is given here.

Main linguistic features:

- Verb final, as the unmarked (though not the only) phrase order.

- Subject before object unless the object is human and the subject is not.

- Complex morphology on both nouns and verbs. Transitive verbs, in particular, have paradigms with several thousand cells.

- A complex system of grammatical relations, in which case-marking on NPs is ergative/absolutive, agreement on verbs is ‘split-S’, with intransitive arguments indexed by prefix on stative verbs and by suffix on dynamic verbs (regardless of agentivity), and grammatical relations (subject, object, indirect object) are composed by integrating case-marking, verbal indexation and other syntactic behaviours.

- Distributed exponence (Carroll 2017) in the verb, which means that most inflectional values (person and number of subject and object, tense, aspect, mood) require the integration of multiple sites on the verb, and even of the verb with free pronouns, for their full interpretation, and that conversely what looks like the same form can have different meanings in different combinations.

- A rich set of diathetic prefixes to the verb, which can either increase their valency (causative, benefactive) or decrease it (reflexive, reciprocal, decausative). Occasionally verbs take more than one such diathetic prefix, sometimes accruing rather idiomatic meanings in the process, e.g. aebyängs ‘to fly (e.g. birds)’, waebyängs ‘to make fly (e.g. a pilot flying a plane)’, awaebyängs ‘1. to swat flies off one’s body, i.e. to make them fly away from oneself; 2. to wait’. Addition of a further benefactive prefix to this latter gives the word wawaebyängs 'to wait for'. Entries from such diathetic families are linked in the dictionary by the label codiathetic, which points to its neighbouring kin in the family chain, e.g. the entry for awaebyängs specifies ‘codiathetic: waebyängs, wawaebyängs’ and the entry for aebyängs specifies .‘codiathetic: waebyängs’. By following these chains of diathetic links, families of verbs related by valency-chaining derivation can be recovered from the dictionary.

- No serial verbs (unlike Papuan languages of the Trans-New Guinea phylum), but widespread use of infinitives inflected for case in various sorts of complex constructions, e.g. onest ‘(in order) to fish with a net’ is built from the infinitive ones ‘to fish with a net’ by adding the allative case suffix -t; ones is itself built from the stem one.

- A composed number system that has either three values (most transitive subjects: singular, dual, plural) or four (objects and intransitive subjects: singular, dual, plural, large plural), and that is unusual in the way that it derives plurals by combining a non-dual (i.e. some number other than two) with a non-singular – consider how the prefixes y- ‘3rd person singular: he, she’ and yä- ‘3rd person non-singular: they’ combine with the stems -kmangr ‘to be lying down (non-dual)’ and -kmaran ‘to be lying down (dual)’ we get the forms ykmangr ‘(s)he is lying down’, yäkmaran ‘they two are lying down’ and yäkmangr ‘they (more than two) are lying down’. The large plural is composed by a baffling variety of means, according to the type of verb, and rather than treat this complex subject here the reader is referred to Evans (2019). Although in many verbs the dual vs non-dual contrast is shown by a regular thematic between the stem and the tense/aspect/mood/subject suffix, there are also many verbs showing more irregular alternations and these are flagged in the dictionary by the labels dual or non-dual pointing to the other form.

- Most verbs in Nen – and the set is large, at around 1,417 out of 5,005 lexical items – employ single words (inflected or infinitive, as appropriate) with no further material. As mentioned in (f), there are many families linked by diathetic prefixes of various sorts, and there are also alternations between stative ‘positional verbs’ like éser ‘to be in water, to be immersed’, causatives like wésers ‘to put in water’, and dynamic middle verbs like esers ‘to come to be in water, to become immersed’. Other than these, and the dual/non-dual stem alternations found with some verbs, there are no appreciable derivational relations between one verb stem and another. Nor are there morphological means for deriving verbs from adjectives or nouns – instead, inchoative predicates are formed by combining the noun or adjective with the middle verb ämts ‘to become’ (e.g. néq-ba nämtenda ‘he got angry; lit. anger-with he.became’) and causative predicates by combing the noun or adjective with wets ‘bring to an end, complete, make’, e.g. snutis etndt ‘they made it slippery’; lit. ‘slippery-only they.made.it’. A relatively small number of other meanings are expressed by the combination of a coverb (typically doubling as a noun) and a verb, e.g. ‘to call back to’ is normally expressed by the phrase ke wawanḡs [lit. ‘noise/shout answer.to’]. A rather larger number of phrasal constructions – running to several dozen – are experiencer object constructions, expressing meanings like ‘to be hungry’: these combine a ‘stimulus noun’, inflected for the ergative, a verb like räms ‘to do’, and place the experiencer in the object role, e.g. ynd gersäm wramte ‘I am hungry’, lit. ‘me hunger-ergative it.does.me’. Phrasal verbs are listed in the dictionary with the coverb or stimulus noun (inflected if required by the construction) followed by the infinitive of the verb, e.g. gersäm räms ‘be hungry, feel hungry’.

Most Nen verbs are simple rather than phrasal. Apart from diathetical alternations like intransitive/causative or transitive/reflexive, there are practically no derivational relationships turning one verb into another, or creating verbs from nouns or adjectives by morphological derivation. This is a property shared with the other Yam languages. It contrasts strongly with Trans-New Guinea languages such as Kalam (Pawley 1993, Pawley & Bulmer 2011), which have given many linguists the impression that it is typical for Papuan languages to have small sets of inflecting verbs and to compose the larger verb lexicon by combining a lexical verb with a coverb (sometimes called a ‘verb adjunct’ in the Papuanist literature).

Types of special information⇫¶

Headword classifications⇫¶

After each headword, information is given about that word’s part of speech or word class. Knowing this gives a summary of how that word behaves grammatically, since parts of speech are classes of words that show the same essential grammatical behaviour.

For example, knowing that a word is a middle verb, we know that its first prefix slot will normally be filled with one of the prefixes, n, k or g (working together with the suffix to express tense, aspect and mood), and that it will take actor suffixes. For example the middle verb owabs ‘speak, say, talk’, occurs in such forms (among hundreds) as nowabm ‘we two are talking’, nowabtam ‘we (several) are talking’, kowabte ‘you (singular) were or (s)he was talking yesterday’, and gowabte ‘you (singular) were or (s)he was talking a long time ago’. At the same time, knowing that a verb is middle also tells us that its subject will be the absolutive case (taking no suffixes), rather than the ergative case found with transitive subjects: dmab nowabte ‘(the) woman is talking’ is correct, but it would be incorrect to say *dmabm nowabte, adding ergative -m to the word for ‘woman’. From knowing a verb is middle, we also know that when it combines with a phasal auxiliary (words like ‘begin’, ‘finish’ and so on) that phasal auxiliary must itself be in the middle form, e.g. opaps ‘begin (middle)’ rather than wapaps ‘begin (transitive)’: dmab owabst nopapnda ‘the woman has begun to talk’ is built by adding the allative suffix -t to the infinitive owabs to give owabst, and combining this with the inflected phasal auxiliary verb opaps, middle form, third person singular past perfective, which is nopapnda ‘(s)he began’.

Contrasting this briefly with a ‘transitive verb’ like renzas ‘carry’, if we know a verb is transitive we know that it will take prefixes from the ‘undergoer’ series denoting its object, and suffixes from the ‘actor’ series denoting its subject. Its subject will take the ergative case (instead of the absolutive case used with a middle verb) and its object will take the absolutive case. And if it combines with a phasal verb, then the phasal verb must be transitive. We can illustrate this with yrenzm, ‘we two are carrying it’, yrenzam ‘we (several) are carrying it’, yrenze ‘(s)he is carrying it, you (singular) are carrying it’, trenzam ‘we (several) carried it yesterday’, and drenzawm ‘we (several) carried it a long time ago’. Combining with two nouns to illustrate the behaviour of case suffixes, we have dmabm yép yrenze ‘the woman is carrying the basket’, with ergative -m now on the noun dmab ‘woman’ to indicate she is doing something to something else. And combining with wapaps ‘begin (something)’ (as opposed to the middle form opaps ‘begin’) we can make sentences like dmabm yép renzast yapapnda ‘the woman began to carry the basket’ built by adding the allative suffix -t to the infinitive renzas, building renzast ‘to carry’, and combining with the inflected phasal auxiliary yapapnda ‘(s)he began it’.

These two examples illustrate the purpose of giving word class information after a word: the headword (e.g. owabs or renzas) tells you how the word is pronounced, the definition (e.g. ‘speak, talk’ or ‘carry’ tells you what it means, and the word class information tells you about how it is used in the grammar, including the changes of form it undergoes, and how it combines with oher words to form phrases and sentences. In the case of middle and transitive verbs, there is even a phonological difference: the infinitives and stems of middle verbs are vowel-initial, and those of transitive verbs begin with consonants.

Usually word classes form predictable clusters of meaning (e.g. nouns designate things, verbs designate actions etc.), but these are not always equivalent from one language to another. For example, the word know is a verb in English, but its Nen meaning-equivalent mete is a predicate adjective, behaving more like the English word ‘knowledgable’ in its grammar: to translate ‘I know, he knows’ into Nen you combine it with the respective forms of the verb ‘to be’, thus: ynd [I] mete wm (literally ‘I know(ledgeable) I-am’, bä mete ym ‘(s)he know (s)he-is’ ‘(s)he know(ledgeable) (s)he-is’.

A final point about word classes: some words are heterosemous and can belong to more than one word class, according to the precise meaning. (English does this too: green can be both an adjective, as in a green leaf, and a noun, as in I like green, and kiss can be both a verb, as in They are kissing, and a noun, as in She gave him a tender kiss). Nen is less radical than English here – it is not possible to zip back and forth between nouns and verbs as in English – but there are pockets of words that regularly have more than one word class, particularly a rather large set of words that can be both abstract nouns and adjectives: brbr ‘fear, shame, shyness (noun); afraid, frightened (adjective)’, qébti ‘dark (adjective); darkness (noun), night, nightfall (noun)’, kr ‘death; dead, the late’. It appears that conversion between adjective and noun classes can go in both directions – a word like qébti includes the suffix -ti, an allomorph of -te ‘having, characterised by’ which regularly derives adjectives from nouns (cf sn ‘tooth’, snte ‘sharp’), plus the noun root qéb ‘shade, darkness’, while with other words the evidence of families of derivates points in the other direction – the curse word kraba 'blast! geez!' is formed by adding the comitative -(a)ba to kr, i.e. ‘by death!’, and -aba is a suffix on nouns, not adjectives. In heterosemous (and also in polysemous) entries I follow the order which seems most likely in terms of semantic and formal derivation, which means that the relative order of noun and adjective senses is not consistent.

In the table that follows, I list the word class labels given in the dictionary, along with a brief explanation of the main characteristics of that word class. I group the word classes into main types (e.g. verbs, pronouns, adverbs) and then deal with different subtypes (e.g. middle verbs, transitive verbs).

| Superclass | Full term | Grammatical behaviour | Meaning profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| adjective | adjective | Modifies noun, typically preceding them in a phrase; can be the predicate of the copula ‘be’, ämts ‘to become’ and wets ‘cause to be, make’. Many adjectives are derived from nouns by adding -te or -ba, both meaning ‘with’, e.g. snte ‘sharp’ (lit. ‘with tooth’), kérbérba ‘cool’ (lit. ‘with cold’), gboba ‘cloudy’ (lit. ‘with cloud’). | Characteristics and properties |

| adjective | predicative adjective | Adjectives, but generally confined to predicate position, where they combine with the copula ‘be’. Sometimes these behave as two-place predicates syntactically; in such cases (e.g. in a statement like ‘I know many languages’) the plurality of the object will be registered by a ‘multal’ use of the prefix ng- on the copula, e.g. ynd terber zi wngm ‘I know many languages’. | States, often directed at others and often translatable by verbs in other languages, e.g. mete ‘know(ing)’, mñte ‘lov(ing)’. |

| adverb | adverb | Super class with many subtypes - see following. Adverbs modulate the whole clause and are generally placed on the clause periphery. | |

| adverb | locative adverb | Give location of the clause event. Some may inflect for locational cases, e.g. pétéq ‘behind’ would normally take the locative (> pétéqan ‘(at) behind’ if locating an object. Others, e.g. nasgis ‘far away’ do not combine with case suffixes. | Location. Typically represent two place predicates, one of whose arguments is the clause as a whole and the other is the location denoted by the adverb |

| adverb | manner adverb | Generally derived from another word by a number of means including reduplication, often with the addition of a sufffix, to either the simple or reduplicated stem, such as -ere (awagsere ‘loaded up’), -e (qabqabe ‘face to face’), -ba (angaba ‘carrying on back’), -ae (tqtqae ‘(making love) in the missionary position’) or -ngama(s) (kramaengama ‘slowly’) mngärngamas ‘quickly’, or sometimes as a phrase by adding the word yam ‘way, manner’ after an adjective. | Manner – spatial layout, pace, gait, type of movement, speed, degree of care etc. |

| adverb | time adverb | Frame an action in time; most commonly occur adjacent to the clause’s subject (before or after). | Time, whether distance from the speech act (e.g. kae ‘±1 day; yesterday/tomorrow’), as a point in a sequence (e.g. prende ‘first’) or as a frequency (e.g. dumni-dumni ‘frequently, always’). |

| clitic | clitic | Join onto a preceding word, adding a range of meanings, e.g. -s ‘only, just’. This can add onto nouns, adjectives, pronouns and so forth, whether inflected or in their basic form. | No common semantics – a very wide range of meanings |

| conjunction | conjunction | Joins two phrases or clauses together, e.g. a ‘and’, ynadbnan ‘because of that, thus’. | Various logical relations of conjunction, purpose, clause, intention |

| coverb | coverb | Word, typically invariant (and often doubling as a noun), that combines with a verb to form a phrasal lexeme denoting an action, e.g the coverb e, denoting a cry, can combine with the verb engs ‘to cry’ to give e engs ‘to cry, to sob’. | Unitisable actions |

| demonstrative | demonstrative | Typically occupies initial position in a determiner phrase, e.g. yna mer dmab ‘this good woman’. May also occur alone, e.g. yna ‘this (one)’. | Deictic word locating object by position or directing addressee’s attention, or following presumed establishment in the discourse. |

| greeting | greeting | Expression used to greet or farewell others, generally part of a two-part pair with echoing by the address | Four time-of-day terms (good morning, good day, good evening, good night) plus ‘goodbye’. |

| intensifier | intensifier | Follow adjectives, negators or nouns to specify the degree to which they possess the specified characteristic; typically last word in the phrase in which they occur | Range of ‘very’, ‘real(ly)’ to ‘properly’ |

| interjection | interjection | Words that are typically uttered in isolation, without syntactic integration | Express an independent conversational move or as a vivid depiction or expression of some state |

| nominal | common noun | Can occupy a NP in its own right (appropriately inflected for case and number) or head the phrase, preceded by such modifiers as adjectives, demonstratives, numerals and possessive phrases | Denotes entities of a wide range of types, including humans, animals, plants, places, manufactured objects, celestial objects etc. |

| nominal | kinship noun | Subset of nouns denoting kinship relations, and hence constituting two place predicates (e.g. ‘my father’ specifies the relation of fatherhood between me and the referent). Unlike other nouns, a subset of these can take prefixes, which are reduced forms of the personal pronouns identifying the pivot of the kin relation with respect to participant roles in the speech act, e.g. tarbe ‘my father’, berbe ‘your father’. | Kinship relations. Only core kinship relations have special prefixed forms (and even they allow alternative expression with a free possessive); more distant kinship relations (e.g. kake ‘grandkin’) do not have prefixed forms. |

| nominal | proper noun | Denotes a person, place, clan or language with a particular designator. | In principle, uniquely identifiable objects rather than classes, but in the case of personal names the practice of namesaking means these are not always unique |

| nominal | title | Combine with personal names to give a polite title, e.g. Bolo Idaba ‘Old Man Idaba’. Derive from nouns of similar semantics, e.g. bolo ‘old man’. | Denote phases of late life |

| numeral | numeral | Numerals belong to an upwardly extendible class using powers of six – a ‘senary’ system. There are simple roots for all powers of six up to 7776, the fifth power of six: ämbs pus ‘six’, ämbs pérta (‘36; 1 x 62’), ämbs taromba (‘216, 1 x 63’), ämbs damno (‘1296, 1 x 64’, ämbs weremaka (‘7776, 1 x 65’). Other numbers are composed by adding multiples of successive powers of six (see example above). Nen has both cardlnal numerals (such as those just given), or ordinal numerals (third, fourth, thirty-sixth etc.) formed by adding either -ta or -ngama to the cardinal numeral. Numerals can occur on their own, or as modifiers inside the noun phrase, e.g. nambis togetoge ‘three children’. | Numbers, cardinal or ordinal. |

| particle | particle | Short, invariant words that colour the interpretation of the sentence in some way. Variable in terms of position in the clause | Range from modal modulation (e.g. ‘maybe’ to expressions of speaker hopes, doubts etc. |

| particle | preverbal particle | Placed just before the verb to modulate its tense and aspectual value, e.g. te ‘already’, baba ‘a short while ago’. | Various time intervals relative to the present, or characterisations of whether the action is complete |

| postposition | locative postposition | Word that follows a noun or noun phrase to specify its location with regard to the clause, or to another entity; may take an appropriate local case, as illustrated by the behaviour of tq ‘top’ in mnḡ tqn ‘on top of the house’ (-n locative), mnḡ tqt ‘onto the top of the house’, mnḡ tqngama ‘from the top of the house’. Many double as nouns, denoting e.g. the top (tq) of something. | Locational characterisations of an object or action with respect to an object or place, where the postposition mentions some aspect of the topology of the reference place (e.g. top, inside) |

| pronoun | indefinite ponoun | Mostly formed from interrogative pronouns, by combining them with ybe or -p, both of which add the sense of non-identifiability by speaker or hearer to the meaning of the pronoun, e.g. nen ‘what’, nenp ‘something; whatever’, ebe ‘who’, ybe ebe ‘whoever’. | Denote members of a category for which the speaker regards clear identification as impossible, e.g. ‘someone’, ‘anyone’. |

| pronoun | interrogative pronoun | Request information from the hearer by specifying one of a set of categories for which the speaker seeks additional knowledge | Comparable to English interrogative pronouns like ‘who’, ‘what’, ‘when’ etc. |

| pronoun | negative pronoun | Complex words formed in a range of ways, based on an interrogative pronoun, the negator yao placed before the verb, and either the word ämb ‘some’ or the suffix -p to the interrogative pronoun. | Words denying the existence of a thing, location, person, etc. |

| pronoun | personal pronoun | Words identifying a referent by their role in the speech act: 1st, 2nd or 3rd person. These show number, plus a rich set of case distinctions; there is no gender or clusivity. Some are morphologically and semantically complex, e.g. bepapns ‘up to you; your business’ is built on be ‘you:oblique’ plus -pap ‘place’ plus -n ‘locative’ plus -s ‘just’. | Closed set corresponding to English ‘I’, ‘you’, ‘me’, ‘my’, etc. |

| pronoun | reflexive pronoun | Formed from possessive pronouns by adding -nzo or -nzos, these translate reflexive or reciprocal pronouns of the type ‘themselves’ or ‘each other’ in English. | Reflexives can be translated as e.g. ‘myself’; the reciprocals meanings are hard to translate literally, meaning something like ‘we-each-other’ and so on. |

| pronoun | relative pronoun | Pronoun used to form relative clauses, of the type the man who I saw, the dog that chased me. Most have (at least) double function, either as interrogative pronouns or as personal pronouns. | Small set of words for introducing relative clauses, mostly based on demonstratives and interrogative pronouns (like English), but with a couple of other possibilities |

| quantifier | quantifier | Cannot take case marking. Can either occur inside the noun phrase, typically at the beginning, or can ‘float’ towards the verb. See Evans (2017) for details on syntax. | Specifies the number of entities involved, in absolute or relative terms. |

| verb | ditransitive verb | Indexes subject on actor (suffix) slot and indirect object on undergoer (prefix) slot; can also index object number by ‘multal’ prefix if number is large; case frame is ergative:absolutive:oblique/dative. Combines with ditransitive phasal auxiliaries in phasal infinitival construction. | Verbs of transfer, whether of objects (e.g. give) or information (e.g. show, teach) |

| verb | experiencer object verb | Combines a ‘stimulus noun phrase’ in the ergative (e.g. gersäm, the ergative of gers ‘hungry; hunger’) with a transitive verb (most commonly räms ‘do to’ and the experiencer in the absolutive. As would be expected from their case roles, the stimulus is indexed by the actor suffix and the experiencer by the undergoer prefix. Word order is normally: experiencer (absolutive) stimulus (ergative) verb, e.g. ynd gersäm wramte [me hunger-ERG me-does-it] ‘I am hungry’ . Analysed as having the experiencer as phrasal verbs with a fixed (transitive) subject and an open object, the experiencer, with the word order reflecting a preference for humans rather than non-humans to come first. In the dictionary, experiencer objects are treated as phrasal verbs, given in the form N-ERG V(INFINITIVE), e.g the above example is entered as gersäm räms (experiencer object verb) ‘be hungry, feel hungry’ |

Physical sensation like ‘be itchy’, ‘be hungry’, ‘be thirsty’, and emotions like ‘be friustrated’. |

| verb | intransitive verb | For Nen this is used in a rather restrictive way, being confined to verbs which index just one argument, using prefixes for person and number (though supplemented by suffixes for dual vs non-dual in the case of positionals, which are a subclass of intransitive verbs). Intransitive verbs thus have their sole argument in the absolutive case, and indexed by undergoer prefix. A further peculiarity of intransitive verbs is that they have no infinitives, apart from ‘go’, which has the suppletive infinitive yls, formally unrelated to any finite form of the root. The commonest intransitive verb is the copula ‘to be’ and its two derivatives ‘come’ and ‘go’, formed by prefixing it for the respective directionals (‘come’ is thus ‘be hither’). Other than these, and the verb ‘walk’, all other intransitives belong to the subclass of ‘positionals’ (see below), which has about forty-five members. Lexicographically it is problematic to select which form to use for the lemma heading of intransitive verbs, since (unlike with the thousand or so other verbs) there is no infinitive. The solution here is to give the root (for the copula and ‘walk) or root + stative suffix (for positionals) followed by the symbol ‘^’ to indicate it cannot occur alone, e.g. m^ ‘be’, erengr^ ‘sit’. Suppletive dual roots are listed separately, e.g. ren^ ‘be (of two)’. This is not a great solution, since Nen speakers do not recognise these as words, but so far no better solution has been found. |

Stative situations (‘be’, ‘be in position’ [many different positions and postures are expressed by different verbs]. However, ‘come’ and ‘go’, formed from ‘be’ by adding directionals, are non-stative members of this class, as is the verb ‘walk’. |

| verb | middle verb (intrinsic) | Take a middle prefix (n-, k- or g- according to tense, aspect and mood), an actor suffix, have their subject in the absolutive, and form phasal constructions with middle auxiliaries. ‘Intrinsic’ middle verbs are not formed by a clear semantic derivation4 from any other verb | Denote dynamic actions involving just one participant, whether controlled (e.g. ogiabs ‘to work’ ) or not (e.g. epers ‘fall (of tree)’. |

| verb | phasal auxiliary | Indicate action ‘phases’, such as beginning, continuing or ending; the verb they modify is placed in an infinitive plus a case suffix, and the phasal auxiliary must match the infinitive in transitivity. The phasal auxiliary carries all the inflectional categories that would have appeared on the main verb if it had been finite – person and number of subject and object, direction, and tense, aspect and mood | Half a dozen verbs denoting phasal transitions or continuations, normally with three diathetically linked versions to go with middle, transitive and ditransitive infinitives |

| verb | positional verb | This is the largest subclass of intransitive verbs. These are prefixing verbs and have special morphological properties, taking a special ‘stative’ suffix -ngr (non-dual) or -aran (dual) not found with other verbs, and, uniquely, form their ‘large plurals’ by combining singular prefixes with dual stative suffixes. They cannot take standard imperatives but can take future imperatives. Each positional verb belongs to a set of three linked lexemes: the positional verb, denoting ‘be in a position’ e.g. ‘be sitting’, the middle verb, denoting ‘get into a position’ (e.g. ‘sit down, get into a sitting position’) and the transitive verb, denoting ‘cause to be in a position’, (e.g. ‘cause to be in a sitting position, place (something), seat (someone)’. | Denotes positions (e.g. ‘be in a tree fork’ or postures (e.g. ‘be sitting’); there are around 45 of these. Many tightly define the figure: ground relations, e.g. ‘be in water’, ‘be wedged into something tight’. See Evans (2014). |

| verb | reflexive/reciprocal verb | a type of middle verb, derived from a transitive verb by the addition of a diathetic prefix comprising an initial vowel (a-, ä-, e-, i-), that indicates action directed back at the initiator (reflexive) or back and forth between two or more parties (reciprocal). With plural subjects, the verb does not distinguish reflexive and reciprocal readings | Productively applied to form verbs where a reflexive or reciprocal relationship is appropriate. Unlike English, which has some ‘naturally reciprocal verbs’ with no overt marking (e.g. ‘they kissed’, as well as ‘naturally reflexive verbs’ (e.g. ‘he shaved’), all reflexive and reciprocal actions are overtly marked as such through the addition of a diathetic prefix to a transitive (or ditransitive) base. |

| verb | resultative participle | Designate the state resulting from an action having been carried out on something; formed by adding the causal suffix -mne to the infinitive form of a verb | States resulting from actions, e.g. ‘cleared’ (of garden), ‘chopped’ (of wood) |

| verb | semi-transitive verb | Morphologically, these look like transitive verbs, indexing both subject and object, but they assign case according to an absolutive:dative frame instead of the ergative:absolutive frame that is found with transitive verbs. | A small set of verbs which involve two participants but where the effect on the second participant is rather indirect, including ‘help’, ‘teach’, ‘load onto’, ‘wait in prey for’. |

Acknowledgments⇫¶

I thank the following organisations for financial support of my work on Nen: the Australian Research Council (Grants: Languages of Southern New Guinea and The Wellsprings of Linguistic Diversity), the Volkswagen Foundation (DoBES project ‘Nen and Tonda’), the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (Anneliese Maier Forschungspreis), the Australian National University (Professorial Setup Grant) and the ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language (CoEDL). Most importantly, I think the entire population of Bimadbn village for their hospitality and friendship, particularly those members of the language and clan committee whose names listed above. Discussions from various colleagues working on other languages of Southern New Guinea have aided immensely in coming to understand what, at the beginning of 2008, was virtually a completely undocumented language family: Marco and Alma Boevé, Matt Carroll, Kipiro Damas, Christian Döhler, Chris Healey, Darja Hoenigman, Penny Johnson, Eri Kashima, Julia Miller, Jeff Siegel.

Discussions about languages of the neighbouring Pahoturi family, from which Nen has borrowed a number of words, have also been helpful, and here I thank Volker Gast, Kate Lindsey and Dineke Schokkin.

Saliha Muradoǧlu has been of great assistance in helping organise and update the data in my Flex files. Finally, I would like to thank the Dictionaria Team – Iren Hartmann and Martin Haspelmath – both for their kind invitation to publish this (still very provisional and imperfect) dictionary in their series, for their editorial comments and corrections, and for their assistance in preparing it for publication in the current format.

For generously allowing me to include their photographs of birds mentioned in this dictionary, I thank Leah Beekman (Broan-backed Honeyeater, Common Koel, Cuckoo-shrike, Grey Whistler, Paperbark Flycatcher, Rufous-banded Honeyeater, male Shining Flycatcher, Spangled Drongo, female Yellow-bellied Sunbird, male Yellow-bellied Sunbird), Rohan Bilney (Australasian Grebe, Barking Owl, Bar-shouldered Dove, Black-backed Butcherbird, Blue-faced Honeyeater, Green Pygmy Goose, adult male Magnificent Riflebird, Noisy Pitta, Orange-footed Scrubfowl, Radjah Shelduck, Red-winged Parrot, Rufous Owl), Rohan Clarke (Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike, Brown Goshawk, Buff-breasted Paradise Kingfisher, Cicadabird, Collared Sparrowhawk, Crested Baza, Dusky Honeyeater, Golden-headed Cisticola, Grey Shrike-thrush, Large-tailed Nightjar, Leaden Flycatcher, female Leaden Flycatcher, Little Paradise Kingfisher, female Mangrove Golden Whistler, male Mangrove Golden Whistler, Orange-bellied Fruit Dove, Pheasant Coucal, Red-backed Button-quail, Red-capped Flowerpecker, Red-headed Myzomela, female Satin Flycatcher, male Satin Flycatcher, Superb Fruit Dove, Uniform Swiftlet, Variable Goshawk, Varied Honeyeater, White-bellied Cuckoo-shrike, White-throated Honeyeater, Wompoo Pigeon), Cliff and Dawn Frith (King Bird of Paradise, Trumpet Manucode), Chris Healey (Australasian Darter, Australian Owlet Nightjar, Australian White Ibis, Black Butcherbird, Black-capped Lory, Black-necked Stork (Jabiru), Black-winged Stilt, Black-winged Stilt, Blue-tailed Bee-eater, Brahminy Kite, Brolga, Domestic Fowl, Eastern Curlew, Eastern Great, Intermediate & Little Egrets, male Eclectus Parrot, Emerald Ground Dove, Great Egret, Great-billed Heron, Greater Streaked Lory, Grey Teal, Grey-headed Goshawk, Helmeted Friarbird, Honeyeater, Intermediate Egret, Little Black Cormorant, Little Kingfisher, Little Pied Cormorant, Magpie Goose, Masked Lapwing, Noisy Friarbird, Northern Fantail, Olive-yellow Flyrobin, Orange-footed Scrubfowl, Pacific Black Duck, Palm Cockatoo, Papuan Frogmouth, Pelican, Pied Heron, Pied Imperial Pigeon, Pinon Imperial Pigeon, Raggiana Bird of Paradise, Rainbow Bee-eater, Royal Spoonbill, Slender-billed Cuckoo-dove, Southern Cassowary, Spangled Kingfisher, Spotted Whistling Duck, Straw-necked Ibis, Tawny-breasted Honeyeater, Torresian Crow, White-bellied Sea Eagle, White-breasted Woodswallow, White-shouldered Fairy-wren, White-spotted Mannikin, White-throated Nightjar, Willy Wagtail, Yellow-bellied Sunbird, Yellow-billed Kingfisher), Darja Hoenigman (Blyth’s Hornbill, Zoe’s Imperial Pigeon), John Hutchison (Azure Kingfisher, Blue-winged Kookaburra, Brown Honeyeater, Brush Cuckoo, Common Sandpiper, Crimson Finch, Hardhead, Large-billed Gerygone, Lemon-bellied Flycatcher, Lemon-bellied Flyrobin, Little Shrike-thrush, Rufous Fantail, Yellow-bellied Flyrobin), Ken Sherring (Comb-crested Jacana, Curlew Sandpiper, Olive-backed oriole, Pied Imperial Pigeon, Plumed Whistling Duck, Shining Flycatcher Female, Striated Heron, Sulphur-crested Cockatoo, Varied triller, Wandering Whistling Duck), and Peter Ware (Leaden Flycatcher and male Leaden Flycatcher).

Plant images are from photos taken by Kipiro Damas, Christian Döhler, Chris Healey, Julia Miller, all of whom I thank for their permission to reproduce them here, in addition to some which I took myself.

Audio files were kindly made available from the Xenocanto website (https://www.xeno-canto.org/ ) under a creative commons licence. For particular recordings I thank: Patrick Åberg, (brum, golaba, kewarkewar, kndrsiesie, korkorp kérpupu, okok, pan brum, pan nnegane, qaraqara, qébti tibrtibr, rera, satoto, saya, sayawa, sépu, siroro, tatawako, wtkowtko, ziwak), Marc Anderson (bogrwiyawiyao [Green/Yellow Oriole], peropero, wambosansa, werwer mémék), Nick Athanas (bñebñeaba wk dédér, kabizalo, kakayamkakayam, kogal, wk dédér), Bas van Balen (awawako, bisaope, boaboak, ḡese [Boyer’s Cuckoo Shrike] kakin serere amni, kiarara, ktekte, pisa, poznzn, pudersge bibd, sayawa, skoptete, yérés amni), Nick Brickle (sosansosan [Painted Quail Thrush]), Mike Catsis (satoto, sosansosan [Blue Jewel Babbler]), Niels Poul Dreyer (wrng brum), Niels Krabbe (dgoa, gondako, keropatpat, korkorp keropatpat, pan zir, qa, skoptete), Frank Lambert (bingi kokopasi, boaboa, bogrwiyawiyao [Brown Oriole], drondro, qaraqara, tara, wlila), Eliot Miller (ḡese [White-bellied Cuckoo Shrike]), Vicki Powys (tutu, wewe), Tom Tarrant (tawaroro), Colin Trainor (soa), George Wagner (yéndri), Woxvold (dépi, ds, qsaqsa). I thank Xenocanto and the generous community of bird enthusiasts for creating this great resource.

References⇫¶

Ayres , Mary. 1983. This side, that side: Locality and exogamous group definition in the Morehead area, southwestern Papua. PhD thesis: Department of Anthropology, University of Chicago.

Boevé, Marco & Alma Boevé. 2000. Alphabet Development Worksheet for socio-linguistic orthography. SIL-PNG: Unpublished MS.

Carroll, Matthew. 2017. The Ngkolmpu language, with special reference to distributed exponence. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Australian National University.

Döhler, Christian. 2016. A grammar of Komnzo. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Australian National University.

Döhler, Christian. 2018. A grammar of Komnzo. Language Sciences Press: Studies in Diversity Linguistics.

Evans, Nicholas. 2009. Two pus one makes thirteen: senary numerals in the Morehead–Maro region. Linguistic Typology 13.2:319-333.

Evans, Nicholas. 2012a. Even more diverse than we thought: the multiplicity of Trans-Fly languages. In Nicholas Evans & Marian Klamer (eds.) Melanesian Languages on the Edge of Asia: Challenges for the 21st Century. Language Documentation and Conservation Special Publication No. 5: 109-149.

Evans, Nicholas. 2012b. Nen assentives and the problem of dyadic parallelisms. In Andrea C. Schalley (ed.) Practical Theories and Empirical Practice. Facets of a complex interaction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Pp. 159-83.

Evans, Nicholas. 2014. 2014. Positional verbs in Nen. Oceanic Linguistics 53 (2), 225-255.

Evans, Nicholas. 2015a. Chapter 26. Valency in Nen. In Andrej Malchukov & Bernard Comrie (eds.), Valency Classes in the World’s Languages. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Pp. 1069-1116.

Evans, Nicholas. 2015b. Inflection in Nen. In Matthew Baerman (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Inflection. Pp. 543-575.

Evans, Nicholas. 2017. Quantification in Nen. In Ed Keenan & Paperno, Denis. (eds.), Handbook of Quantifiers in Natural Language. Vol. 2. Springer Studies in Linguistics and Philosophy, vol 97. Pp. 573-607.

Evans, Nicholas. 2019. Waiting for the word: distributed deponency and the semantic interpretation of number in the Nen verb. In Matthew Baerman, Andrew Hippisley and Oliver Bond (eds.) Morphological Perspectives. Papers Honours of Greville G. Corbett. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Pp. 100-123.

Evans, Nicholas, Wayan Arka, Matthew Carroll, Yun Jung Choi, Christian Döhler, Volker Gast, Eri Kashima, Emil Mittag, Bruno Olsson, Kyla Quinn, Dineke Schokkin, Philip Tama, Charlotte van Tongeren and Jeff Siegel. 2018. The languages of Southern New Guinea. In Bill Palmer (ed.), The Languages and Linguistics of New Guinea: A Comprehensive Guide. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Pp. 641-774.

Evans, Nicholas & Julia Miller. 2016. Nen. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 46.3:331-349. Available on CJO2016. doi:10.1017/S0025100315000365.

Kashima, Eri. In prep. A mixed methods investigation of language variation in Nmboland, Southern New Guinea. PhD Thesis, Australian National University.

Lee, Jenny Soyeon. 2016. Split Intransitivity in Ranmo. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences.

Ross, Malcolm. 2005. Pronouns as a preliminary diagnostic for grouping Papuan languages. In Andrew Pawley, Robert Attenborough, Jack Golson and Robin Hide (eds.). 2005. Papuan Pasts: Cultural, Linguistic and Biological Histories of Papuan-Speaking Peoples. Pp. 15–65.

Siegel, Jeff. 2014. The morphology of tense and aspect in Nama, a Papuan language of southern New Guinea. Open Linguistics 1(1): 211–231 DOI:10.2478/opli-2014-0011.

Williams , Francis E. 1936. Papuans of the Trans-Fly. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Footnotes⇫¶

1 In 1981 Ayres recorded two Nen women, Dgma Amto and Zagma, residing in the village of Govav. Dgma Amto is still alive. I have transcribed both these stories and they have been incorporated into the Nen corpus.

2 In the Boevé and Boevé orthography these were written as kw, gw and ngw. but these are poor representations of the phonetics. Neither kw or kp (and likewise for other sequences) are possible graphemic representations if one adopts the epenthetic-schwa analysis used here, since in both cases these are possible two-consonant sequences with schwas inserted between them.

3 [ə] or [ɐ] can also be a realisation of unstressed word-initial /a/, in verbs where the stress falls on the root away from the diathetic prefix, e.g. /ətors/ ‘exit’. Speakers prefer to write this as <a>.

4 Though there may be more idiosyncratic relationships, as between wabs ‘count’ and owabs ‘talk’ – cf English count and recount, and German zählen ‘count’ and erzählen ‘tell, recount’.

| Full Entry | Headword | Part of Speech | Meaning Description | Scientific Name | Semantic Domain | Examples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Text | Analyzed Text | Gloss | Translation | IGT |

|---|---|---|---|---|