Wersing dictionary

The language and its speakers⇫¶

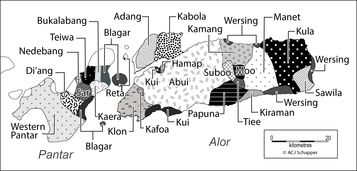

Wersing (ISO 639-3: kvw) is a language spoken on the island of Alor in the Nusa Tenggara Timur province of Indonesia. The speakers of Wersing traditionally live in settlements scattered amongst other languages along the north, south and east coasts of central-eastern Alor (Map 1). On the north coast, there are two distinct settlements, one centred on the village of Adagai in the west and the other around Taremana in the east. These villages are in close contact with varieties of Abui and Kamang speakers respectively and villagers typically have some competency in those languages. On the east coast, the Wersing settlement is centred on the village Kolana, containing a mix of Wersing and Sawila speakers. Along a small portion of the south coast, Wersing villages are strung from Mademang in the West to Pureman in the East. These villages neighbour Kiraman-, Manet- and Sawila-speaking villages. According to local traditions, the settlements in Pureman on the south coast constitute the original Wersing settlement, with the settlement on the east coast having occurred later and from there further on to the north coast.

Map 1: Papuan languages of Alor and Pantar

There are no reliable sources of how many Wersing speakers there are. The most recent edition of the Ethnologue (Eberhard, Simons & Fennig 2020) cites Grimes’ et al. (1997: 65-66) estimate of 3,700 speakers. In the villages, Wersing appears to be still being learnt by at least some children in places such as Kolana (Emilie Wellfelt pers. comm.), Pureman (Hans Retebana pers. comm.) and Mademang (personal observation). Shift to Indonesian or, better said, the local variety of Malay spoken in Alor, is proceeding apace: schooling and literacy is exclusively available in Indonesian, and increasingly speakers move away from the villages of Wersing-speaking areas for the purposes of further education and employment.

Wersing belongs to the Alor-Pantar subgroup of the language family known as the Timor-Alor-Pantar family (Holton et al. 2012, Schapper et al. 2014, Schapper 2017). Wersing is part of the low-level East Alor sub-group, within which it groups by itself, with Montane-East-Alor containing its neighbours, Kula and Sawila, as a sister node (Schapper 2018). Recent higher classifications, such as Ross (2005), have included the Timor-Alor-Pantar languages in the hypothesized large family, Trans-New Guinea, but that link is not proven.

Alor is a small island where Papuan languages dominant. The surrounding islands are inhabited by speakers of Austronesian languages (with a few exceptional pockets of Papuan languages on distant parts of Timor). All of the Papuan languages of Alor show layers of borrowing from Austronesian, but as a coastal group, the Wersing have a more significant amount than most. In particular, contact with the peoples of the northern coast of Timor and to the islands east of Alor have left clear cultural and linguistic marks on the traditions and language of the Wersing people (see Schapper and Wellfelt 2018).

Previous work on Wersing has been limited. I know of the following work. Mark Donohue conducted several days of fieldwork in Kolana in the 1990s; this resulted in a manuscript of a phonological sketch on the Wersing dialect of that place (Donohue 1997) as well as scattered examples in published works (e.g., Donohue 2004: 226 on metathesis, 2008: 66-67 on alignment). A Wersing reader was produced in the mid-2000s by Fredik Langko, a native speaker of Kolana Wersing and retired primary school teacher, in order to support local content curriculum (muatan lokal) teaching (Langko n.d.). Holton (2010) is a 400-item wordlist collected in Kalabahi, the capital of Alor, with a Wersing speaker from Taramana, on the north coast of Alor. A slightly extended version of the same wordlist was collected by Choi (2015) for Maintaing dialect. Holton (2014) includes a set of Wersing kin terms based on elicitation of genealogies. Schapper & Hendery (2014) is a sketch grammar of Wersing Pureman, to which the materials presented here provide some significant updates.

Bible translations are another potential source of material for the study of Wersing. A preliminary version of the gospel of Mark in Wersing was translated by Anderias Malaikosa (n.d.), a native speaker of Wersing and Sawila from Kolana. Subsequent to the passing of Malaikosa in 2012, a team of native speakers and bible translators from the Unit Bahasa dan Budaya has been working on translations of further books of the bible on the basis of the Kolana dialect (Unit Bahasa & Budaya 2017, 2019). As part of that work, Johnny M. Banamtuan has presented a detailed analysis of metathesis in Wersing Kolana (Banamtuan 2018) and developed together with the translation team a working orthography for the Kolana dialect (Unit Bahasa & Budaya 2020).

Source of the data⇫¶

All material in this dictionary was collected by the author working with a single speaker, Hans Retebana, between 2012 and 2020.

Retebana is a native speaker of the Peitoko variant of the Pureman dialect on Alor’s south-eastern coast. Retebana grew up in Peitoko speaking Wersing. In late adolescence he moved to Kalabahi, the capital of Alor, where he lived and worked in local government for the remainder of his life. He regularly visits Pureman where many of his family still reside, but does not use Wersing on a daily basis. As a result, Retebana’s active recall of certain lexical domains, such as farming and subsistence, biota names as well as traditional religion, is limited. His phonology and morphology form an internally consistent system (as described below), but may not be typical of the Pureman speech community in general.

The backbone of the lexical materials presented here were collected in an initial intensive workshop of two weeks in Bali in 2012. In this time, the present author and collaborator Dr. Rachel Hendery assembled a corpus of several hundred elicited utterances, responses to five MPI stimuli tasks, and seven narrative texts. On the basis of that initial work, a sketch of Wersing was published (Schapper & Hendery 2014). As part of a comparative-historical project, I continued work with Retebana on the lexicon of Wersing. Further elicitation was conducted in Kalabahi as follows: two days in July 2013, two weeks in November 2015, two weeks in April 2016, two weeks in April 2018 and three weeks in March 2019. In these elicitation sessions, the emphasis of my work was not on collecting more lexical items but rather was directed towards getting accurate phonological renderings, particularly in regards to stress, semantically differentiating lexical items which had been translated in the same way into Indonesian, and collecting example sentences for each item.

The material presented here is thus significantly restricted by the limited speaker base (one individual!) and the mode of its collection. The user should be aware, therefore, of the imperfect and incomplete nature of these lexical materials. I publish them here for the benefit of the Wersing community, of Papuanists concerned with comparative-historical issues, and of linguists with an interest in lexical typology.

Wersing phonology and morphology⇫¶

I do not include a sketch grammar here since this was already presented in Schapper and Hendery (2014). Nonetheless, it is necessary to update and elaborate on some aspects of the analysis of phonology and morphology based on the further data collected subsequent to the publication of the 2014 sketch. Where there are differences between Schapper and Hendery (2014) and this publication, the reader should take the information presented here as authoritative. I focus here on information that will be of use to the reader in understanding the structure of the Wersing lexicon and this dictionary representation of it.

Phonology and orthography⇫¶

Phonemes. Table 1 shows the inventory of consonants, using both in IPA letters and in the graphemes of the practical writing system. The /r/ phoneme is marginal in word-initial position, being found in two known loans only. The /ɲ/ phoneme is found initially in little over a dozen person forms all marked for the 1st person plural exclusive, with one exception, /mleɲa/ ‘yesterday’. The phoneme /ŋ/ is marginal in onsets; it is not found at all word-initially and in only three lexemes as a medial onset. The phonemes /n/ and /ŋ/ merge in codas, with [ŋ] being the only realization.

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voiceless stop | /p/ <p> | /t/ <t> | /k/ <k> | |

| Voiced stop | /b/ <b> | /d/ <d> | /g/ <g> | |

| Nasal | /m/ <m> | /n/ <n> | /ɲ/ <ny> | /ŋ/ <ng> |

| Voiceless fricative | /s/ <s> | |||

| Lateral | /l/ <l> | |||

| Trill | /r/ <r> | |||

| Semi-vowel | /w/ <w> | /j/ <y> |

Table 1. Consonant phonemes (//) and their corresponding graphemes (< >) in the Wersing orthography

There are five vowels in Wersing. These are shown in Table 2. The vowel /o/ tends to be realized as [o] in closed syllables and [ɔ] in open ones.

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| High | i <i> | u <u> |

| Mid | ɛ <e> | o <o> |

| Low | a <a> | |

Table 2. Vowel phonemes (//) and their corresponding graphemes (< >)

Vowel sequences. Sequences of a non-high vowel followed by a high vowel occur within a single syllable nucleus and can optionally be realised as a diphthong. For example, /-pai/ ‘make’ is sometimes realised with a steady low F1 followed by an abrupt jump to a steady high F1 [pai]. In other instances, there is a smooth slide from a low point to a higher target [paj]. The phoneme /u/ can also be realised as [w] before another vowel. In the “Pronunciation” field of each dictionary entry, I write vowel sequences that can be realized as diphthongs with a glide (e.g., {pei} ‘pig’ [pej], {nau} ‘no’ [naw]). This is done as a contrast to sequences of vowels that are not in the same syllable and therefore cannot be realized as diphthongs. In these cases, we often find phonetic glides inserted, but these are not written in the practical orthography used here (e.g., {uing} /ˈuiŋ/ ‘hide’ [ˈu.ʷiŋ], {diari} /diˈari/ ‘fry’ [di.ˈʲari]).

Sequences of two like vowels sometimes arise in Wersing through affixation, e.g., /lε-εsεl/ ‘APPL-tired’, /mi-ilεl/ ‘APPL-look’, /pkoda-a/ ‘burst-FIN’. In such situations, vowels are typically realized with a weak intervening epenthetic glottal stop or a slight pause. In the practical orthography, these are written simply as double vowels, e.g., {leesel}, {miilel} and {pèkodaa}.

Allophony. There is some allophonic variation in the realization of Wersing phonemes. I discuss here those cases which also impact on the orthographic rendering of words in this dictionary:

- Word-initial /w/ may be elided on many, but not all, items before /o/ and /u/, e.g., /wota/ [wɔta ~ ɔta] ‘coconut’, /wuli/ [wuli ~ uli] ‘spill’. In these cases, I permit both renderings in the practical orthography, {wota} ~ {ota} ‘coconut’, {wuli} ~ {uli} ‘spill’.

- There is no contrast between /n/ and /ŋ/ in codas. In the practical orthography used here, in codas {ng} is written, while in onsets {n} is used, e.g., {oming} ‘here.NFIN’ versus {omin-a} ‘here-FIN’.

- Nasal assimilation is common, both within and across words, where final /ŋ/ is adjacent to a consonant with another place of articulation: e.g., /-maŋtaiŋ/ ‘strike’ can be realised as [-maŋtajŋ] or [-mantaiŋ]; /tεŋ=bo/ ‘first.NFIN=EMPH’ can be realised as [tεŋ=bɔ] or [tεm=bɔ]. As a rule, I do not use nasal assimilated forms in Wersing orthography but maintain underlying /ŋ/ as {ng}.

- Root-initial /j/ frequently weakens on prefixation, with the result the now adjacent vowels may be realized either distinctly with a weak intervening epenthetic glottal stop or as a single long vowel that e.g., /lɛ-ˈjar/ [lɛjar ~ laˀar ~ laːr] ‘tell a story’, or /gɛ-ˈjɛm/ [gɛjɛm ~ gɛˀɛm ~ gɛːm] ‘call him/her’.1. In the practical orthography, these items are written as realized by the speaker, e.g., /lɛ-ˈjar/ ‘tell a story’ can be written variably {lejar} ~ {laar}.

- Final high vowels following a consonant can also be dropped. For instance: /-ˈwεri/ ‘ear’ can be realised as [-wεri ~ -wεr] and /t<na~>ˈnasu/ ‘each’ can be realised as [tənanasu ~ tənanas]. For consistency, I always write the final vowels with such items as these.

- /o/ may be realized in some items as either [ɔ] or [u] finally and in some cases preceding a final high vowel, e.g., /bo/ [bɔ ~ bu] ‘clausal demonstrative’, /atoku/ [atɔku ~ atuku] ‘earth’, /adosi/ [adɔsi ~ adusi] ‘gourd’. However, I only render /o/ as orthographic {o} and never as {u}. Where /o/ can be realized as [u], I note this in the “Pronunciation” field as far as possible.

- On a small number of items, an unstressed vowel can irregularly be reduced to schwa. For example, /miˈra/ ‘inside’ can be realised as [miˈra ~ muˈra ~ məˈra] or /giˈnuk/ ‘3.DU’ can be realised as [giˈnuk ~ gəˈnuk]. In the practical orthography, these items are written as realized by the speaker, i.e., {mira} ~ {mura} ~ {mèra} and {ginuk} ~ {gènuk}.

Stress. Stress is unpredictable in Wersing, but Schapper and Hendery (2014) had not identified stress-differentiated minimal pairs at the time of publication. Since then, I have noted some, but the number remains small:

| (1) | /aˈmi/ ‘breast’ | ≠ | /ˈami/ ‘there’ |

| /aˈmuiŋ/ ‘submerge’ | ≠ | /ˈamuiŋ/ ‘cape’ | |

| /aˈtok/ ‘your stomach’ | ≠ | /ˈatok/ ‘peck, lunge at’ | |

| /suˈak/ ‘prawn’ | ≠ | /ˈsuak/ ‘store sharp object’ |

Given the low functional load stress carries, I do not mark stress in the practical orthography used here. The reader can check where stress falls in the “Pronunciation” field of each entry.

Vowel reduction and onset vowel epenthesis. The low functional load carried by stress today in Wersing is partly due to very many historically pre-tonic vowels being lost from original initial CV syllables.2. The loss of these pretonic vowels means that Wersing has a large number of roots with underlying initial consonant clusters, i.e., have the shape CCV(C)(V)(C). Most of these consonant clusters are broken up through vowel epenthesis between C1 and C2. The epenthetic vowel may be [ə] or harmonised with the first vowel of the root, as in the examples in (2). In the practical orthography used here, the non-phonemic, epenthetic vowel is written with {è}.

| Underlying | Realisation | Orthography | Etymology | |

| (2) | /mˈtari/ ‘rosewood’ | [məˈtari ~ maˈtari] | {mètari} | < PTAP *matari |

| /tpa/ ‘new’ | [tǝˈpa ~ taˈpa] | {tèpa} | < PTAP *tipa | |

| /mdi/ ‘plant’ | [mǝˈdi ~ miˈdi] | {mèdi} | < PTAP *mudi[ŋ] |

Some, but not all, underlying initial consonant clusters involving plosive+liquid and fricative+plosive/liquid are permissible in surface forms. In these situations, the writing of {è} is optional in the orthography. For example:

| Underlying | Realisation | Orthography | |

| (3) | /ski/ ‘arrow’ | [ˈski ~ səˈki ~ siˈki] | {ski} ~ {sèki} |

| /slar/ ‘coral cliff’ | [ˈslar ~ sǝˈlar ~ saˈlar] | {slar} ~ {sèlar} | |

| /priŋ/ ‘corpse’ | [ˈpriŋ ~ pǝˈriŋ ~ piˈriŋ] | {pring} ~ {pèring} | |

| /bloiŋ/ ‘write’ | [ˈblojŋ ~ bəˈlojŋ ~ boˈlojŋ] | {bloing} ~ {bèloing} |

The use of {è} for the epenthetic vowel in the orthography is motivated by the need to avoid the confusion of the Modern Indonesian orthography’s use of {e} for both /e/ and /ə/. In examples of written Wersing that I have seen, native speakers tend to replicate the Indonesia use of {e} for schwa. However, in Wersing there are a number of lexical items that require /e/ to be differentiated from the epenthetic vowel. For example, in an Indonesian-style orthography, the lexical items in (4) would be both rendered as {meleng}:

| Underlying | Realisation | Orthography | |

| (4) | /mlɛŋ/ ‘night’ | [məˈlɛŋ ~ mɛˈlɛŋ] | {mèleng} |

| /ˈmɛlɛŋ/ ‘scared’ | [ˈmɛlɛŋ] | {meleng} |

A more practical orthographic solution for the future may be not to write the epenthetic vowel at all. However, the native speaker I worked with was reluctant to have this, insisting that a vowel grapheme was needed.

Echo vowels and vowel epenthesis between syllables. Word-final codas can be brought into line with the preferred open syllable shape by means of an echo vowel. An echo vowel is harmonized with the preceding phonemic vowel, as in (4). Unlike an epenthetic vowel, an echo vowel is never schwa (e.g., /pis/ ‘mango’ can be realised as [pisi] but not *[pisə]).

| Underlying | Realisation | Orthography | |

| (5) | /pis/ ‘mango’ | [pis ~ pisi] | {pis} ~ {pisi} |

| /bεb/ ‘palm top’ | [bεb ~ bεbε] | {beb} ~ {bebe} | |

| /war/ ‘and’ | [war ~ wara] | {war} ~ {wara} | |

| /pok/ ‘little’ | [pok ~ poko] | {pok} ~ {poko} | |

| /tuk/ ‘short’ | [tuk ~ tuku] | {tuk} ~ {tuku} |

Not all final Cs precipitate echo vowel insertion to the same extent. For example, /pur/ ‘garden’, and /tam/ ‘grandchild’ are always found in the corpus without echo vowels. By contrast, /pok/ ‘little’ and /pis/ ‘mango’, for example, are found both with and without echo vowels, but more often with. That is, liquids and nasals generally remain as word-final codas, but other underlying consonant codas tend to have an echo vowel appended to them. The conditioning factors for the (non-) appearance of the echo vowel remain to be determined by means of a statistical analysis of a fuller corpus.

Consonant clusters across syllable boundaries, i.e., roots with the shape (C)VC.CV(C), may also be broken up by vowel epenthesis where stress is on the last syllable. Where these clusters are broken up, the epenthetic vowel is never schwa but, like an echo vowel, always harmonized with the preceding vowel of the root. For example:

| Underlying | Realisation | Orthography | |

| (6) | /gε-lokˈmaŋ/ ‘3-head’ | [gεlokˈmaŋ ~ gεlokoˈmaŋ] | {gelokmang} ~ {gelokomang} |

| /bεtˈkol/ ‘grasshopper’ | [bεtˈkol ~ bεtεˈkol] | {betkol} ~ {betekol} | |

| /bilˈkai/ ‘papaya’ | [bilˈkaj ~ biliˈkaj] | {bilkai} ~ {bilikai} | |

| /sakˈpul/ ‘cloud, fog’ | [sakˈpul ~ sakaˈpul] | {sakpul} ~ {sakapul} | |

| /sirˈwis/ ‘work’ | [sirˈwis ~ siriˈwis] | {sirwis} ~ {siriwis} |

In the practical orthography used here, these echo and epenthetic vowels are written in example sentences where they are uttered by the language consultant. I include them because in many instances they appear to be required for utterances to be phonologically well-formed. Head words never include an echo vowel.

Agreement morphology⇫¶

Table 3 presents the four paradigms of agreement prefixes found on nouns and verbs in Wersing. The analysis of each of these represents a refining of the one put forward in Schapper and Hendery (2014).

| Series I | Series II | Series III | Series IV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1SG | n- | ne- | na- | nai- |

| 2SG | a- | e- | a- | ai- |

| 3 | g- | ge- | ga- | gai- |

| 1PL.EXCL | ny- | nye- | nya- | nyai- |

| 1PL.INCL | t- | te- | ta- | tai- |

| 2PL | y- | ye- | ya- | yai- |

Table 3. Wersing agreement prefixes

The relationship between roots, the prefixal series they occur with and the argument they index is highly lexicalized in Wersing. It therefore constitutes essential information for many entries in this dictionary (See fields labelled “Inflectional class” in the dictionary entries). In what follows, I describe the known distribution and function of each of the four prefixal agreement series.

Series I. This paradigm of agreement prefixes is, by far and away, the most frequently occurring in Wersing. On vowel-initial roots, the prefixes are realised as per their underlying forms, with the exception of the 2nd person singular person which is indicated by the absence of a prefix. On consonant-initial roots, the consonantal prefixes (i.e., all but 2SG) surface as an unstressed CV syllable, where the V is epenthetic. As with other epenthetic vowels breaking up initial consonant clusters, this may be realised as either a schwa or a vowel harmonised with the left-most root vowel and is written with {è}. Examples are provided in Table 4.

| -atok ‘belly’ | -ornai ‘dream’ | -teng ‘hand’ | -mit ‘sit’ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1SG | n- | natok | nornai | nèteng | nèmit |

| 2SG | a- | atok | ornai | ateng | amit |

| 3 | g- | gatok | gornai | gèteng | gèmit |

| 1PL.EXCL | ny- | nyatok | nyornai | nyèteng | nyèmit |

| 1PL.INCL | t- | tatok | tornai | tèteng | tèmit |

| 2PL | y- | yatok | yornai | yèteng | yèmit |

Table 4. Prefixation of roots with Series I

When used in the nominal domain, Series I prefixes index the possessor of nouns belonging to the lexical class of inalienably possessed nouns. Examples include -atok ‘belly’ and -teng ‘hand/arm’ in the above table. See here for more information about possessive classes.

Series I prefixes occur on verbs indexing S, P or A. It is lexically determined which argument is indexed by a Series I prefix. While the lexical classes of verb with S and P agreement using a Series I prefix are large, the class with A agreement has only a handful of members. The following examples illustrate the different arguments that can be indexed by a Series I prefix:

| Series I prefix agreeing with S | |||||

| (7) | a. | nè-tai | kana | ||

| 1SG-sleep | already | ||||

| ‘I’m already sleeping.’ | |||||

| Series I prefix agreeing with P | |||||

| b. | guru | nè-mosi | |||

| teacher | 1SG-help | ||||

| ‘The teacher helps me.’ | |||||

| Series I prefix agreeing with A | |||||

| c. | naida | kape | nè-nai | naung | |

| 1SG.TOP | coffee | 1SG-eat/drink | NEG | ||

| ‘I don’t drink coffee.’ | |||||

A handful of verbs show variable agreement behaviour with Series I prefixes. Differential agreement is typically related to transitivity and semantics. However, the relationship between prefixed and unprefixed forms of a verb root is largely idiosyncratic and the different appearances of these roots vis-a-vis agreement are treated as separate lexical entries in the dictionary. Examples of verbs occurring with different agreement patterns are:

| (8) | a. | eta | beting | ong | mai | (transitive, no agreement) |

| 2SG.AGT | bamboo | use | come | |||

| ‘You bring bamboo.’ | ||||||

| b. | Daud | gè-mai | (intransitive, S agreement) | |||

| David | 3.I-come | |||||

| ‘David came.’ | ||||||

| (9) | a. | naida | meleng | (intransitive, no agreement) | ||

| 1SG.TOP | scared | |||||

| ‘I am scared.’ | ||||||

| b. | ne-pa | nè-meleng | (transitive, P agreement) | |||

| 1sg.III-father | 1SG.I-scared | |||||

| ‘My father threatens me.’ | ||||||

| (10) | a. | kubung | nadi | pasi | (transitive, no agreement) | |

| mosquito | 1SG.OBL | bite | ||||

| ‘The mosquito bit me.’ | ||||||

| b. | akoling | nè-pasi | naung | (transitive, A agreement) | ||

| dolphin | 1SG.I-bite | NEG | ||||

| ‘I don’t eat dolphin.’ | ||||||

Series II. This paradigm of agreement prefixes is most commonly used in the nominal domain. They index the possessor of nouns belonging to the lexical classes of alienably possessed and obligatorily possessed nouns. See here for more information about possessive classes.

With verbs, Series II agreement prefixes make a very limited appearance, obligatorily indexing either S or P. For the most part, the use of Series II prefixes appears to be phonologically conditioned, occurring on monosyllabic verbs beginning with y (e.g., -ya ‘go down’, -yok ‘shake (tr/intr)’) or an unstressed syllable tè (e.g., -tème ‘hear’, -tènar ‘teach’). Two verb roots, -yem ‘call’ and -tèter ‘shiver’, show mixed agreement behaviour, preferring Series I prefixes in some persons and Series II prefixes in others. Only one verb taking Series II prefixes does not fit these shapes, -kui ‘fart’.

Series II prefixes have an additional use on verbs marking inceptive aspect. Unlike the above use obligatorily indexing an argument, this use is entirely optional and occurs to the left of an agreement prefix that is lexically specified to a verb. Compare the marking of the verb -tati ‘stand’ in (11). In (11a) where the verb shows the normal agreement pattern with a single Series I prefix indexing S, we have a straightforward sequence of events whereby the cat moves into a standing position and then jumps on its prey. In (11b) where both a Series I prefix and, to its left, a series II prefix index S on -tati, the act of standing is only in its first phase: the cat holds itself in a half-standing position, poised to jump.

| (11) | a. | akamau | gè-tati | ba, | kengel | gè-wai | durki | wuing | gewen=a |

| cat | 3.I-stand | DEF | jump | 3.I-go | mouse | grab | 3.POSS=SPEC | ||

| ‘The cat stands and jumps to catch the mouse.’ | |||||||||

| b. | akamau | ge-gè-tati | ba, | kengel | gè-wai | durki | wuing | gewen=a | |

| cat | 3.II-3.I-stand | DEF | jump | 3.I-go | mouse | grab | 3.POSS=SPEC | ||

| ‘The cat is half standing ready to jump to catch the mouse.’ | |||||||||

Series III. The prefixes of this paradigm are found almost exclusively on verbs marked with the applicative prefix le- (see here). The referent coindexed by a Series III agreement prefix is, with a few exceptions, always the same as the P applied by le-. It is obligatory for first and second person referents of P to be indexed with a Series III prefix on verbs marked by le- (i.e., oblique pronouns cannot be used), it is optional for third person referents of P. For example, take the intransitive verb ko ‘cry’ (12a). When le- is prefixed to the verb, a second argument, the stimulus for the event is added to the clause. This second participant can be either encoded with or without a Series III prefix, (compare 12b and 12c). According to the native speaker judgement I had access to, where there is no prefix, the stimulus is vaguer; the child cries for want of the mother, but the mother is no-where to be seen. By contrast, with the Series III prefix, the child can see the mother and she is directly available to respond to the child’s demands.

| (12) | a. | ol | pok | ko | |

| child | small | cry | |||

| ‘A child cries.’ | |||||

| b. | ol | pok | ge-ya | le-ko | |

| child | small | 3.II-mother | APPL-cry | ||

| ‘A child cries for its mother (who is not visible/available).’ | |||||

| c. | ol | pok | ge-ya | ga-le-ko | |

| child | small | 3.II-mother | 3.III-APPL-cry | ||

| ‘A child cries for its mother (who is visible/available).’ | |||||

In the dictionary there are only two intransitive verbs marked by le- which are known to be able to take a Series III prefix indexing their S argument, lesèweri ‘be scattered about’ and -leboli ‘be without success’. The use of Series III prefixes to index an S argument on an le-marked verb may be available on more roots than the materials collected here make clear.

Because a Series III prefix occurs to the left of le-, it is in a different slot to a Series I prefix, which always occurs closest to the root. The two can, therefore, cooccur. For example, when marked by le-, the verb -mur ‘run’ in (13) hosts a Series I prefix for the derived A (S of the verb in its underived form) and a Series III prefix for the applied P.

| (13) | naida | ne-ya | ga-le-nè-mur-a |

| 1SG.TOP | 1SG.II-mother | 3.III-APPL-1SG.I-run-FIN | |

| ‘I run from my mother.’ | |||

There are only two intransitive verbs without le- on which a Series III prefix is known to occur: -mèra ‘want’ and -mèlosi ‘not want’. On these two verbs, the appearance of the Series III prefix is obligatory and can be considered to be in the same slot as other obligatory agreement prefixes of Series I and, to a lesser extent, Series II. Given that the two verbs share the same initial unstressed syllable mè and that they are the only verbs of that shape to take agreement prefixes, it seems likely that this use of Series III is phonologically conditioned.

Series IV. The prefixes of this paradigm are found only on verbs and are the least frequent prefixal series in my data. Schapper and Hendery (2014) tentatively suggest that Series IV prefixes may be contractions of Series I prefixes and applicative le-. On examination of more data, this suggestion does not seem to be supported. However, the functions of the Series IV prefixes remain poorly understood and the account provided here is still preliminary.

The single most frequently attested use of Series IV prefixes is indexing P with at least some transitive verbs. In a similar manner to Series III prefixes with le-, on four verb roots it is obligatory for first and second person referents of P to be indexed with a Series III prefix on these verbs, but it is optional for third person referents of P. On two further transitive verb roots, this pattern in suspected, but I lack examples without the Series IV prefix in the third person to confirm this.

On two other verb roots, the use of Series IV prefixes adds a second participant and is associated with a change in meaning. The intransitive verbs -sir (Series I prefixes for S) ‘descend’ and tèbel ‘wrong’ can both take a Series IV prefix indexing a P (replacing the Series I prefix on the former root) to mean ‘bear, give birth to (lit. descend out of)’ and ‘blame’, respectively.

On only one intransitive verb in my corpus, lalang ‘sick’, is a Series IV prefix used for S. Here the prefix is optional and, where it is used, denotes greater affectedness of S. However, because the pattern is, at this stage, only known from a single verb and it is not clear that it is generalized, I list the prefixed and unprefixed form of this verb as separate lexical entries.

Applicative morphology⇫¶

Wersing has two applicative prefixes: le- and mi-. Each has several frequently occurring functions, most applicativizing, but others not. See the entries for each of the applicative prefixes for details.

While many appearances of applicative prefixes on roots yield predicable semantics, there is also a reasonable amount of lexicalization to be observed. Take, for instance, boli ‘bad’ which becomes le-boli ‘wounded’ and naung ‘not’ becomes mi-naung ‘disappear, be not present’. While the semantic relationship between these unprefixed roots and their applicative-marked forms is not difficult to perceive, there is an element of unpredictability in the semantics of applicative-marked forms.

In addition, some roots do not exist in a “bare” form. These are of two types. The first involves forms which are invariable. For example, the root alar is only known to occur as mi-alar ‘sail’ in Wersing, but it is clear that mi- is an applicative on etymological grounds. The second involves roots that only occur in morphologically complex forms including with applicative prefixes. For example, the bare root sebi is not attested in Wersing, but it is found in the applicative marked forms le-sebi ‘ask about’ and -le-sebi ‘ask of’, and the compound -mak sebi ‘ask (someone)’.

For these reasons, applicative prefix-marked roots are listed in the dictionary as separate lexical entries. The only exception to this is numerals, a word class for which there appears to be a complete lack of lexicalization in meanings of applicative marked forms. Because of this, I do not list applicative-marked numerals separately. The reader should note that I have not systematically checked the availability of each of the two applicative prefixes on roots. Therefore, absence of an applicative-marked root from the dictionary should not be taken to indicate its non-existence.

Metathesis and final/nonfinal contrasts⇫¶

Wersing has a synchronic process of metathesis involving final unstressed syllables containing a high vowel. The default shape of a word displaying metathesis i.e., the form which is given in elicitation or list contexts, differs in Wersing depending on the consonant involved in the metathesis. Where the metathesising consonant is n (with ŋ as its final allophone), the default shape is (CV)ˈCVV[+high]ŋ and the metathesised shape is (CV)ˈCVnV[+high]. By contrast, lexemes that do not have n as the metathesising consonant have the default shape (CV)ˈCVCV[+high] and the metathesised shape is (CV)ˈCVV[+high]C.3. I use the default shape as the citation form, i.e., the form given as the headword in the dictionary. The metathesised form of an item is given after information, if any, about inflectional class. Note, again, that I have not systematically checked the availability of metathesis on roots of the appropriate shape; metathesised forms are only recorded where they were offered by the speaker I worked with as alternative shapes or were spontaneously produced, e.g., as part of example sentences for other head words.

Metathesis is triggered on nouns by encliticisation of =a ‘SPEC’ (compare saku ‘elder’ in 14a and 14b) and on some verbs by suffixation of -a ‘FIN’ to final predicates (compare -tati ‘stand’ in 15a and 15b). The suffix -a ‘FIN’ on these and other predicates was described as a realis marker by Schapper and Hendery (2014) because it marks that a situation or event has been realized and is a statement of fact.

| (14) | a. | Hans | sauk=a | amin-a | ||

| Hans | elder=SPEC | dist-BE.LOC-FIN | ||||

| ‘Hans is there.’ | ||||||

| b. | Kris | saku | ba | g-atok | sibai | |

| Kris | elder | def | 3.I-belly | basket.type | ||

| ‘Chris has a fat belly (lit. a basket belly).’ | ||||||

| (15) | a. | gèning | weting | gè-tait-a | ||

| 3.CLF:HUM | five | 3.I-stand-FIN | ||||

| ‘Five people are standing.’ | ||||||

| b. | mei | poko | gè-tati | gè-bir | ak | |

| female | small | 3.I-stand | 3.I-mouth | open | ||

| ‘A girl stands with her mouth open.’ | ||||||

On other verbs, it does not appear that -a ‘FIN’ can be used. Instead, metathesis is triggered on these by syntactic position. In a non-final position in the clause the consonant-final form is used (a examples in 16 and 17), while the vowel-final forms are used in clause final position (b examples in 16 and17). The vowel-final forms of these verbs seem to carry with them the same realis mood denoted by -a ‘FIN’ on other verbs.

| (16) | a. | ne-tamu | ong | areing=te |

| 1SG.II-grandparent | use | bury=PRIOR.FIN | ||

| ‘Take my grandmother off to be buried.’ | ||||

| b. | ne-tamu | mèlenya | areni | |

| 1SG.II-grandparent | yesterday | bury | ||

| ‘Grandmother was buried yesterday.’ | ||||

| (17) | a. | mei | pok=a | ge-nimbat | le-kuir | tuk-tuk |

| female | small=SPEC | 3.II-headhair | APPL-comb | keep.on | ||

| ‘The girl kept combing her hair.’ | ||||||

| b. | mei | pok=a | ge-nimbat | le-kuri | ||

| female | small=SPEC | 3.II-headhair | APPL-comb | |||

| ‘The girl combed her hair.’ | ||||||

The final/nonfinal distinction is not only manifested in Wersing by means of -a ‘FIN’ and metathesis on verbs, but is also found with a range of other items involving an unproductive -ng ‘NFIN’ suffix. For example, the priorative marker has the non-final form teng (18a) and the final (encliticizing) form =te (18b).

| (18) | a. | naida | ira | ba | nè-nai | teng | ge |

| 1SG.TOP | water | DEF | 1SG.I-drink | PRIOR.NFIN | PROSP | ||

| ‘I'm going to drink the water first.’ | |||||||

| b. | Ira | ba | a-nai=te | ||||

| water | DEF | 2SG.I-drink=PRIOR.FIN | |||||

| ‘Drink the water first.’ | |||||||

A slightly more complicated relationship exists between the locative postposition =mi (19a), the non-final form of the locative verb ming (19b) and the final form of the locative verb mina (19b).

| (19) | a. | Pur-asi | deing | ilu | gè-bitir=mi | ailak | mèdi |

| Pureman-inhabitant | PL | river | 3.I-side=LOC | sweet.potato | PLANT | ||

| ‘The people of Pureman plant sweet potatoes by the side of the stream.’ | |||||||

| b. | Ol | mèrung | dein=a | n-apa | ming=du | ||

| children | small | PL=SPEC | 1SG-beneath | BE.LOC.NFIN=QUANT | |||

| ‘The children are all beneath me.’ | |||||||

| c. | Akamau | mede | apa | min-a. | |||

| cat | table | beneath | BE.LOC-FIN | ||||

| ‘A cat is beneath the table.’ | |||||||

Other items displaying similar final/nonfinal distinctions involving -ng ‘NFIN’ suffix are the locative demonstratives and the elevationals.

Parallel compounds⇫¶

“Parallelism” is used here to refer to a pattern of coordinative compounding that functions to expand the Wersing lexicon of nouns and verbs. “Parallel” compounds involve compounding of noun with noun or verb with verb, where the relation between members is like one of coordination.4. The pairing of items together in parallel compounds is lexically fixed, as is the order of items in the compounds; new parallel compounds are not readily coined and switching the order of items in already existing ones results in ungrammaticality. The nouns and verbs of a parallel compound occur within a single intonation contour; no pause may intervene between the two Ns or Vs compounded together. They also cannot be independently modified or determined.

Parallel compounds may be created by compounding together items that are (near-)synonyms, antonyms or specific terms denoting related actions or referents. When verbs are compounded together, parallel compounds have meanings denoting intensive situations, repetitive actions or multitudes of participants (examples given in 20). When two nouns are compounded together, parallel compounds create a general cover term for a unitary category or denote plurality of kinds (examples given in 21).

| V V parallel compounds | ||

| (20) | dudung asiding ‘be fluey, have a cold’ | < dudung ‘cough’, asiding ‘sneeze’ |

| -pesi wesi ‘fight intensely, slaughter many’ | < -pesi ‘cut’, wesi ‘shoot’ | |

| muing mèlasur ‘very smelly, stinking’ | < muing ‘smell’, mèlasur ‘smell rotten’ | |

| lat tèresi ‘very flat, completely smooth’ | < lat ‘flat’, tèresi ‘same, identical’ | |

| N N parallel compounds | ||

| (21) | sob mèna ‘settlement, all houses in village’ | < sob ‘house’, mèna ‘village’ |

| keng badu ‘clothing, clothes’ | < keng ‘cloth’, badu ‘shirt’ | |

| -ya -pa ‘parents’ | < -ya ‘mother’, -pa ‘father’ | |

| idem olik ‘all the family, everyone’ | < idem ‘senior relative’, olik ‘junior relative’ | |

In many Wersing parallel compounds, one member of the compound, typically the second member, does not occur independently outside of the compound. In these cases, speakers typically say that the non-independent member ‘means the same thing’ as the other item in the compound. Examples are given in (22). A question mark ‘?’ indicates that the item does not occur outside the compound.

| (22) | kowas bis ‘very rich, very wealthy’ | < kowas ‘rich’, bis ? |

| yer salu ‘laugh a lot’ | < yer ‘laugh’, salu ? | |

| bisar mèngada ‘converse, talk back and forth’ | < bisar ‘speak’, mèngada ? | |

| ladi -tati ‘stand in large numbers, stand in a bunch’ | < ladi ?, -tati ‘stand’ | |

| dèra sek ‘songs of all types’ | < dèra ‘song, sing’, sek ? | |

| -wak -lolol ‘all four legs, limbs’ | < -wak ‘foot’, -lolol ? | |

| moi -barang ‘both shoulders’ | < -moi ?, -barang ‘shoulder’ |

Because of the highly lexicalised nature of parallel compounds in Wersing, they are given their own separate entries in this dictionary.

The dictionary⇫¶

Structure and content of dictionary entries⇫¶

Every entry contains minimally a lexeme written in the Wersing orthography established here, information on pronunciation, the lexeme’s part of speech and an English translation. These the obligatory fields for all lexical entries:

-

Headword (lemma): where a lemma is a noun or verb marked with an initial hyphen "-", this indicates that is must be inflected with a person-number prefix

-

Pronunciation: broad IPA rendering of head word including stress and agreement prefix shape (see Wersing phonology and morphology on Wersing phonology)

-

Part of speech: word class designation (abbreviations and explanations of the characteristics of each part of speech can be found in here)

-

Meaning description: approximate definition in English

Most entries also contain example phrases or sentences as follows:

-

Example sentence in Wersing

-

English translation

Where relevant and available, I include additional information in the following optional fields:

-

Inflectional class: for nouns and verbs, this field provides information about the series of agreement prefix (I, II, III or IV) a root hosts; where no inflectional class information is given, a root is not part of a closed inflectional class (see Agreement morphology on the distribution and function of agreement prefixes, and Applicative morphology on the verbal and nominal classes they define).

-

Metathesised form: for lexical items with the appropriate shape, this field gives their metathesised shape (see Metathesis and final/nonfinal contrasts for details on metathesis as a process).

-

Morphological structure: where a head word is polymorphemic complex (excluding agreement prefixes which are not given in headwords), this is indicated in this field.

-

Grammatical note: This field provides extra information about the grammatical behaviour of a headword, often in one of its senses.

-

Phonological note: This field provides extra information about the phonological behaviour of a headword.

-

Variant: This field is used for noting unpredictable variants of a headword, e.g., where an unstressed vowel can irregularly be reduced to schwa, or where a short form of a morphologically complex headword exists

-

Borrowed word: This field provides information about borrowings from Austronesian languages. Often the precise source language is not known, but indicative forms from nearby Austronesian languages are provided, along with Austronesian etymologies where they are available.

Abbreviations⇫¶

| adv | adverb |

| art | article |

| circump | circumposition |

| clf | classifier |

| conj | conjunction |

| coord | coordinator |

| conn | connector |

| dem.nom | nominal demonstrative |

| dem.cl | clausal demonstrative |

| dem.inter | interrogative demonstrative |

| dem.loc | locative demonstrative |

| dem.mann | manner demonstrative |

| dem.pro | pronominal demonstrative |

| elev | elevational |

| inter | interrogative |

| intj | interjection |

| n | noun |

| n+vi | subject phrase |

| n+vt | object phrase |

| num | numeral |

| part | particle, unclassified |

| plw | plural word |

| postp | postposition |

| prep | preposition |

| pro | pronoun |

| tag | interrogative tag |

| vd/t | optionally ditransitive verb |

| vi | intransitive verb |

| vt | transitive verb |

Table 5. Abbreviations for parts of speech and affixes

| 1 | first person |

| 2 | second person |

| 3 | third |

| AGT | agentive |

| APPL | applicative |

| DEF | definite |

| DIST | distal |

| FIN | final |

| LOC | locative |

| PL | plural |

| POSS | possessive |

| PRIOR | priorative |

| PROSP | prospective |

| QUANT | universal floating quantifier |

| NFIN | non-final |

| SG | singular |

| SPEC | specific |

| TOP | topic |

Table 6. Glosses (only in the introductory text and in some notes)

In addition to the parts of speech of independent words, agreement prefixes in the dictionary are divided into different types according to their function and position (Table 7).

| A | most agent-like argument of a di/transitive verb |

| P | patient-like argument of a transitive verb |

| R | recipient-like argument of a ditransitive verb |

| S | single argument of an intransitive verb |

| T | theme-like argument of a ditransitive verb |

| INAL | inalienably possessed (Series I taking) class of nouns |

| OBL | obligatorily possessed (Series II taking/possessive compound) class of nouns |

| I | Series I agreement prefixes |

| II | Series II agreement prefixes |

| III | Series III agreement prefixes |

| IV | Series IV agreement prefixes |

Table 7. Inflection class abbreviations in the dictionary

In the meaning descriptions, several general abbreviations are used as follows:

| e.g. | for example |

| etc. | et cetera |

| lit. | literal translation |

| i.e. | id est |

Table 8. General abbreviations

Parts of speech⇫¶

Parts of speech can be identified on the basis of their morphosyntactic properties. After each headword in the dictionary, information is given about that word’s part of speech. Table 5 lists all parts of speech which the dictionary contains. The properties of these parts of speech are set out in brief below.

Some words can belong to more than one word class in Wersing. For example, pèdot is an intransitive verb meaning ‘old (of things)’ and an adverb meaning ‘for a long time’; muing is an intransitive verb meaning ‘emit a smell, stink’ and a noun ‘smell, stink’. Because the Dictionaria structure does not permit multiple word class specifications per head word, words belonging to more than one word class get split over separate entries. This means that they are treated in the same way as homophones, even though they are not.

Verbs⇫¶

Verbs in Wersing are defined by the fact that they have valency and take arguments. Intransitive verbs (vi) take a single argument, S. Transitive verbs (vt) take two arguments, A and P. A small number of verbs are optionally ditransitive (vd/t), taking A, T and R.

Verbs can be divided into inflection classes based on their agreement behaviour. There are three parameters of variation here:

-

Series of agreement prefix used

-

Argument indexed by agreement prefix

-

Obligatoriness of agreement prefix

Semantics plays little to no role in determining inflectional class; assignment is entirely lexical.

The largest class of verbs are those that never take an agreement prefix for any of their arguments. This open class is indicated in the dictionary by the absence of information on inflectional class.

For those verbs that do take agreement prefixes, this is noted with a roman numeral (I, II, III, IV) indicating the series of the inflection followed by a letter (A, S, P, R) indicating the argument that the prefix indexed, e.g., I_A indicates that the verb takes a Series I prefix indexing the A argument. Where a verb only optionally takes an agreement prefix (without any significant change in meaning), this is indicated by brackets around the roman numeral and letter, e.g., (III_P) indicates that the P argument can be optionally indexing with a Series III prefix (as is common for transitive verbs marked with le-).

Nouns⇫¶

Nouns are divided into three lexical classes based on the coding of their possessor. They are:

-

Alienably possessed nouns: large open class of nouns on which a possessor is coded with Series II prefixes, but is never obligatory

-

Inalienably possessed nouns (inal): closed class of nouns, typically denoting body parts, on which a possessor is obligatorily coded with Series I prefixes

-

Obligatorily possessed nouns (obl): closed class of nouns, typically denoting kin terms and body parts, on which a possessor is obligatory coded, either as a Series II prefix or as a simple N in a possessive compound

Because their membership is lexically determined, only nouns belonging to the latter two classes are indicated in the field “Inflectional class” (abbreviated as “inal” and “obl”) in the dictionary. Nouns with no inflectional class information in the dictionary belong to the open class of alienably possessed nouns.

In a few cases, nouns may belong to more than one class. For example, lèmi is an alienably possessed noun meaning ‘man’, but an obligatory possessed meaning ‘husband’. Where a root belongs to two separate inflectional classes, they are listed as separate entries in the dictionary.

Multiword phrases⇫¶

In the Wersing dictionary I include two kinds of multiword phrases that involve conventionalised combinations of nouns and verbs. These are not compounds; in each case the noun can be expanded into a noun phrase, for example, by being marked with the definite article.

Subject phrases. Abbreviated as n+vi, these are conventionalised combinations of a bodypart noun in the S role together with an intransitive verb.

Object phrases. Abbreviated as n+vt, these are conventionalised combinations of a noun in the P role together with a transitive verb.

Pronouns⇫¶

Pronouns in Wersing are, for our purposes, personal pronouns. They are marked for person, number, and clusivity. Like other Timor-Alor-Pantar languages, Wersing has numerous paradigms of pronouns, marking variously agentivity, topic, focus, quantity and possession (see Schapper and Hendery 2014 for description of the functions of some paradigms). All pronouns are morphologically complex, but cannot be easily broken down into component morphemes synchronically. Table 9 presents the different paradigms of pronouns identified thus far.

| Agentive | Non-Agentive | Topic | Focus | Additive | Alone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1SG | neta | nadi | naida | newe | nèbaka | nènasu |

| 2SG | eta | adi | aida | ewe | abaka | anasu |

| 3 | geta | gadi | gaida | gewe | gèbaka | gènasu |

| 1PL.EXCL | nyeta | nyadi | nyaida | nyewe | nyèbaka | nyènasu |

| 1PL.INCL | teta | tadi | taida | tewe | tèbaka | tènasu |

| 2PL | yeta | yadi | yaida | yewe | yèbaka | yènasu |

| Independent | Dual | All | Group | Together | Possessive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1SG | nenal | – | – | – | – | neweng |

| 2SG | enal | – | – | – | – | eweng |

| 3 | genal | ginuk | gènaing | gawi | gèmarang | geweng |

| 1PL.EXCL | nyenal | nyinuk | nyènaing | nyawi | nyèmarang | nyeweng |

| 1PL.INCL | tenal | tinuk | tènaing | tawi | tèmarang | teweng |

| 2PL | yenal | yinuk | yènaing | yawi | yèmarang | yeweng |

Table 9. Wersing pronominal paradigms

Demonstratives and articles⇫¶

Demonstratives in Wersing are defined by the fact that they are distanced marked for proximal versus distal. There are different sets of demonstrative and most of them are characterised by their hosting of the deictic prefixes o- ‘PROX’ and a- ‘DIST’. Otherwise the different sets of demonstrative do not share morphosyntactic properties in common.

Two sets of demonstrative, the nominal and clausal demonstratives, form a paradigm with articles. Together they are called ‘determiners’ here (Table 10). In the nominal domain, there are two articles =a ‘SPEC’ and ba ‘DEF’, in the clausal domain only one, bo ‘EMPH’. Only one determiner can be used per NP/clause.

| Nominal | Clausal | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Article | =a | ba | bo |

| Proximal | oba | obo | |

| Distal | aba | abo | |

Table 10. Determiners

Another two sets of demonstrative, the restrictive and interrogative demonstratives, can be used pronominally in “identificational” contexts (Table 11). The functions of these demonstratives are not well-understood at this stage.

| Restrictive Demonstrative | Interrogative Demonstrative |

|---|---|

| o(po)kida | otrona |

| a(po)kida | atrona |

Table 11. Pronominal demonstrative

Locative demonstratives (Table 12) refer to location by distance. The proximal and distal forms are based on the locative postposition =mi ‘LOC’ and its predicative counterpart ming/mina ‘BE.LOC.NFIN/FIN’. The non-predicative locative demonstratives are notable for their added distance dimension, a super-distal indicating a location far from both speaker and addressee, that is not found with any other demonstrative set.

| NPRED | PRED.NFIN | PRED.FIN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal | omi | oming | omina |

| Distal | ami | aming | amina |

| Super-Distal | ang | – | – |

Table 12. Locative demonstratives

The final set of demonstratives are manner demonstratives (Table 13). These differ from other sets in that they do not show marking with the deictic prefixes o- ‘PROX’ and a- ‘DIST’.

| Proximal | pang |

| Distal | pong |

Table 13. Manner demonstratives

Elevationals⇫¶

As in other TAP languages, Wersing has a set of elevationals (Table 14). These distinguish locations on three levels of elevation relative to the deictic centre: LEVEL ‘location at same elevation as the deictic centre’, HIGH ‘location at a higher elevation than the deictic centre’, and LOW ‘location at a lower elevation than the deictic centre’.

| non-final | final | final | final | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEVEL | mong | =mo | mono | mona |

| HIGH | tong | =to | tono | tona |

| LOW | yong | =yo | yono | yona |

Table 14. Elevationals

Like locative demonstratives, elevationals have different forms for final and nonfinal positions. At this stage it is not fully understood what governs the choice between different final forms of the elevationals. The enclitic forms and the forms ending in /o/ cannot stand on their own and must combine with a verb, while forms in /a/ can act as stand-alone predicates.

Numerals and classifiers⇫¶

Numerals. In Wersing numerals are defined by their ability to be used either by themselves or in combination with one another to denote specific quantities. Wersing has simple numerals for the numbers ‘one’ to ‘six’. Higher numerals involve combinations based on the numeral weting ‘five’, adayoku ‘ten’, aska ‘hundred’ or ribu ‘thousand’. Specifically, Wersing makes use of a quinary base for forming numerals ‘seven’ to ‘nine’ (e.g., weting tu five-three ‘eight’) and a decimal base for ‘ten’ and above (e.g., adayoku mi-yoku gresing tu ten MULTIPLY-two plus three ‘twenty-three’).

Classifiers. Wersing has a very small number of dedicated numeral classifiers that optionally occur between a noun and a numeral. These classifiers are items that co-occur in the context of a numeral, classifying the referent of a noun that is being counted. I do not count items to the class of classifiers that can independently occur as nouns, even though there are several that regularly appear between nouns and numerals, e.g., iko ‘seed’.

Like other Alor-Pantar languages, Wersing also has an obligatory inflecting classifier used when enumerating human referents with a numeral above ‘one’, e.g., saku mei ganing weting old.person female 3.CLF:HUM five ‘five old ladies’. The inflectional pattern of the human numeral classifier makes it similar to a paradigm of pronouns (as given above in Table 9).

Conjoiners, connectors and coordinators⇫¶

Wersing has three small classes that are used to join linguistic units to one another.

Conjoiners. Wersing has a small number of enclitic clause conjoiners (conj) that attach to the end of a clause and conjoin it to a following one. The enclitic clause conjoiners often attach to the pronoun geweng where they still occur at the end of the clause.

Sentence connectors. These are clause-initial elements (conn) used to link one clause to another. Enclitic clause conjoiners can form sentence connectors when they mark the manner demonstrative pang.

Coordinators. Wersing has two coordinators (coord) that are used to connect words of the same part that are to be taken either jointly or as alternatives to one another.

Plural words⇫¶

Wersing has two plural words. These are independent words that occur in the NP to optionally mark the plurality of the NP referent. Other non-numeral quantifiers appear to be intransitive verbs.

Interrogatives and question tags⇫¶

Interrogatives (inter) are lexical items that occur in questions indicating what part of the proposition the asker wishes to know about. They may be used pronominally, adnominally and sometimes adverbially.

Question tags (tag) can be used to mark polar questions. They appear as the last element in a clause and are accompanied by rising intonation.

Adpositions⇫¶

Adposition is not a unitary category in Wersing.

The language has one postposition (postp) =mi marking locative relations. This is an enclitic that attaches to a noun or noun phrase to specify its location with regard to the clause; it can never act as the head of an independent predicate. The postposition is related to the verb ming ~ mina ‘be in, at’ and the applicative prefix mi- ‘LOC’.

Similative relations may be expressed by either a preposition (prep) iwe [NP] or a related circumposition (circump) iwe [NP] gèning ‘be alike to, be similar to’. Unlike the locative postposition =mi, the simulative pre/circumposition can act independently as a predicate.

A final preposition lèmang ‘until’ (also a sentence connector) exists in Wersing. Like the locative postposition =mi, this item cannot stand as an independent predicate.

Interjections⇫¶

These are words that are typically uttered in isolation, without syntactic integration in the clause. These include a small number of “vocatives”, a subclass of interjections expressing the identity of the party spoken to.

Adverbs⇫¶

Adverbs (adv) are defined here as modifiers of constituents in the clause other than nouns. This is a sizeable but highly heterogenous group that can be treated as a unitary “class” with difficulty. They can be used to express time, manner, aspect, negation and occur in many different positions in the clause.

Particles⇫¶

Particles (part) are a small heterogenous group of items that chiefly fulfil semantic and pragmatic functions.

Acknowledgments⇫¶

I thank the following organisations for financial support of my work on Wersing: the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (VENI project “The evolution of the lexicon: Explorations in lexical stability, semantic shift and borrowing in a Papuan language family”), the Volkswagen Stiftung (DoBeS project “Aru languages documentation”), the Australian Research Council (project DP180100893 “Waves of words”), and the European Research Council OUTOFPAPUA project, grant agreement no. 848532).

Most importantly, I thank Hans Retebana for his extremely dedicated work and interest in this dictionary. We hope to print an Indonesian version of the Wersing dictionary for the community in the near future.

Discussions from various colleagues working on other languages of the Timor-Alor-Pantar family have also helped immensely: Emilie Wellfelt, Rachel Hendery, Alex Veloso, Juliette Huber, Hein Steinhauer. Discussions about borrowing from Austronesian languages have also been helpful, and here I thank Chuck Grimes, Owen Edwards, Timothy Usher and Sander Adelaar.

Footnotes⇫¶

1 Such weak glottal stop epenthesis/vowel lengthening has also been observed on one vowel-initial item also: /le-adu/ ‘lean on’ [lɛadu ~ laʔadu ~ laːdu]. It may be that the root here is, in fact, /-jadu/.

2 Word-initial vowels, stressed or unstressed, have not been lost. In a few instances, an original pretonic vowel is found preserved in a morphologically derived form of the root. For example, compare /ttuk/ ‘talk, speak’ with derived transitive form /ˈnatutuk/ ‘inform, let know’. Because the prefix /na-/ attracts stress, the /u/ vowel of the initial syllable of the root in this item was not in a pretonic position and so did not reduce.

3 I know of two items on which metathesised forms take a different shape: mèduli ‘suck’ becomes mudil, while sruing ‘rifle’ becomes surin-.

4 Other terms exist in the literature for such compounds, including ‘coordinative’ compounds, ‘dvandva’ compounds, ‘appositional’ compounds, and ‘co-compounds’. The term ‘parallel’ compound is used here, because it is the established term for the eastern Indonesian region where Wersing is spoken. In this region parallel compounds are one expression of what is a wider pattern of parallelism or dyadic pairing in language pervading different speech levels (see Grimes et al. 1997: 15ff).

References⇫¶

Banamtuan, Johnny M. 2018. Metathesis in Wersing: A non-Austronesian language of eastern Alor. Paper presented at the Seventh East Nusantara Conference, Kupang May 14-15.

Choi, Hannah. 2015. Wersing Maritaing wordlist. LexiRumah. URL: https://lexirumah.model-ling.eu/lexirumah/languages/wers1238-marit

Donohue, Mark. 1997. Kolana: syllables, (small) words and CV. Unpublished manuscript, The Australian National University.

Donohue, Mark. 2004. Typology and Linguistic Areas. Oceanic Linguistics 43(1): 221–239.

Donohue, Mark. 2008. Semantic alignments systems: what’s what, and what’s not. In Mark Donohue & Søren Wichmann, The Typology of Semantic Alignment, 24–76. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eberhard, David M., Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2020. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Twenty-third edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. URL: http://www.ethnologue.com.

Grimes, Charles E., Tom Therik, Babara Dix Grimes and Max Jacob. 1997. A Guide to the people and languages of Nusa Tenggara. Kupang, Indonesia: Artha Wacana Press.

Holton, Gary. 2010. Wersing Taramana wordlist. LexiRumah. URL: https://lexirumah.model-ling.eu/lexirumah/sources/holton10

Holton, Gary. 2014. Kinship in the Alor-Pantar languages. In Marian Klamer (ed.), The Alor-Pantar languages: History and Typology, 199–245. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Holton, Gary, Marian Klamer, František Kratochvíl, Laura Robinson & Antoinette Schapper. 2012. The historical relation of the Papuan languages of Alor and Pantar. Oceanic Linguistics 51.1: 86–122.

Langko, Fredik. n.d. Bahasa Daerah Kolana: Diri Sendiri. Unpublished manuscript. Kalabahi & Kolana, Alor Indonesia.

Malaikosa, Anderias. n.d. Yesus Sakku Geleworo Kana. Unpublished manuscript. UBB-GMIT Kupang, Indonesia.

Schapper, Antoinette. 2017. Introduction to The Papuan languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar. Volume II. In Antoinette Schapper (ed.), The Papuan languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar. Sketch grammars: Volume 2, 1–54. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.

Schapper, Antoinette. 2018. Reconstruction of Proto-East Alor. Paper presented at the Seventh East Nusantara Conference, Kupang May 14-15.

Schapper, Antoniette & Rachel Hendery. 2014. Wersing. In Antoinette Schapper (ed.), The Papuan languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar. Sketch grammars: Volume 1, 439-504. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.

Schapper, Antoinette, Juliette Huber & Aone van Engelenhoven. 2014. The relatedness of Timor-Kisar and Alor-Pantar languages: A preliminary demonstration. In Marian Klamer (ed.), The Alor-Pantar languages: History and Typology. 99–154. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Schapper, Antoinette & Emilie Wellfelt. 2018. Reconstructing contact between Alor and Timor. Evidence from language and beyond. NUSA: Linguistic studies of languages in and around Indonesia 64: 95–116.

Ross, Malcolm. 2005. Pronouns as a preliminary diagnostic for grouping Papuan languages. In Andrew Pawley, Robert Attenborough, Robin Hide & Jack Golson (eds.), Papuan pasts: Cultural, linguistic and biological histories of Papuan-speaking peoples, 15–66. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Unit Bahasa & Budaya. 2017. Tuhan Yesus Geloworo Kang Markus gebloing glol. Kupang: UBB-GMIT. [Gospel of Mark in Wersing.]

Unit Bahasa & Budaya. 2019. Tuhan Yesus geutusan deing Getutuk. Kupang: UBB-GMIT. [Acts of the Apostles in Wersing.]

Unit Bahasa & Budaya. 2020. Bahasa Wersing: sistem penulisan. (Trial edition, for internal use). Kupang: UBB-GMIT. [Orthography guide]

| Full Entry | Headword | Part of Speech | Meaning Description | Inflection Class | Pronunciation | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Text | Analyzed Text | Gloss | Translation | IGT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Details | Name | Title | Year | Author | BibTeX type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|