Teanu dictionary (Solomon Islands)

The Teanu language⇫¶

Welcome to this online Teanu – English dictionary.

Teanu is the main language spoken on Vanikoro, in Temotu, the easternmost province of the Solomon Islands. It has about 1000 speakers. Most of them live on Vanikoro, yet many also live in the country’s capital Honiara, on Guadalcanal island.

|

| Fig. 1 - Location of Vanikoro, in the eastern Solomons. |

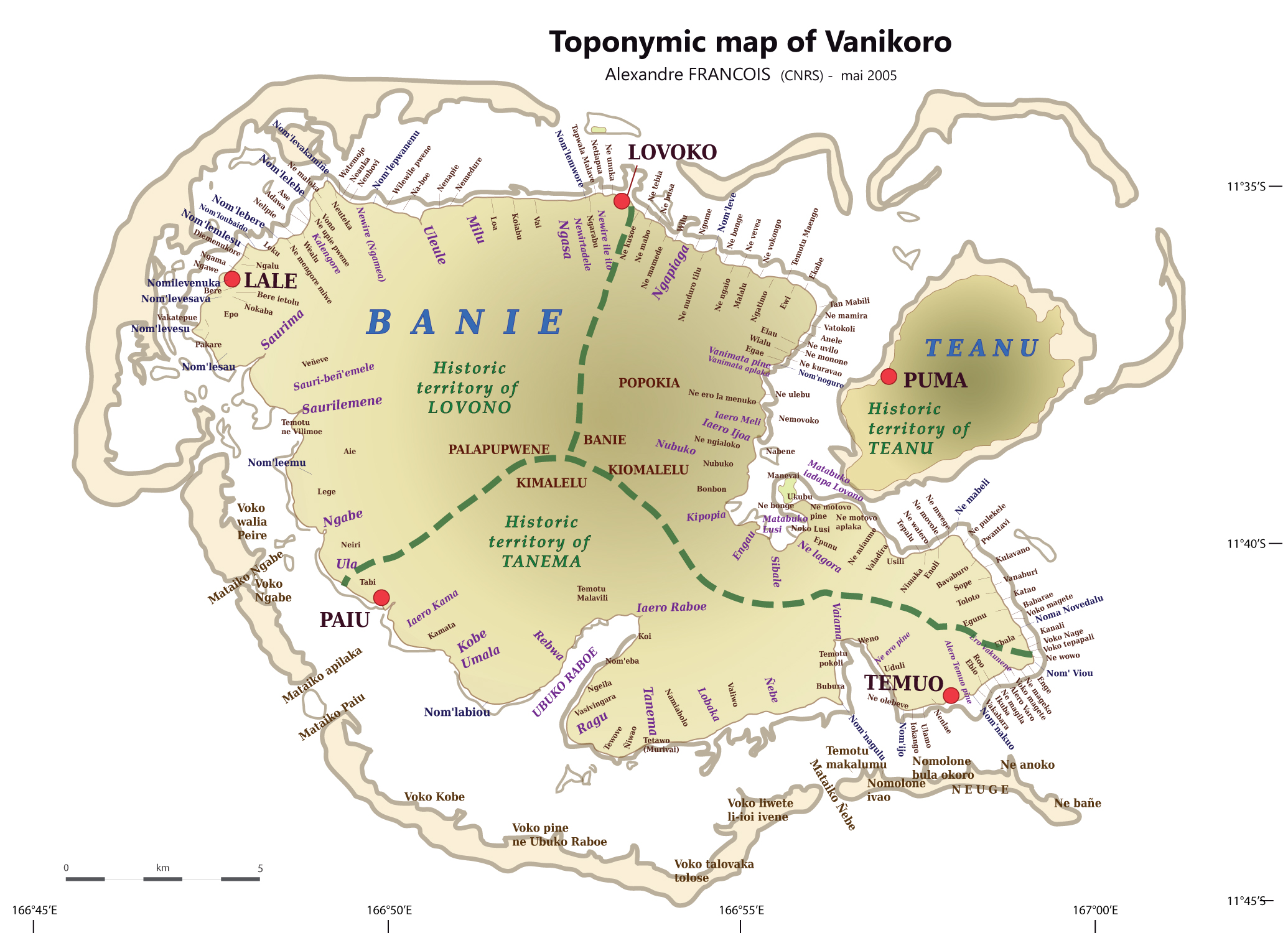

While “Vanikoro” is commonly talked about as if it were a single island, it is technically a cluster of islands, surrounded by a single belt of coral reef. The largest island is Banie, followed by Teanu [Fig. 2]; the latter gave its name to the language spoken in the northeast area of Vanikoro. The same language has also been known in the literature as Puma or Buma (e.g. Tryon 2002), after the main village on Teanu island.

Vanikoro's traditional context is a society of fishermen and farmers – growing tubers, raising pigs and poultry.

The languages of Vanikoro⇫¶

In earlier times, the island group of Vanikoro used to be divided into three tribal territories, whose historical boundaries are still well remembered today. Each tribe had its distinctive language: Teanu in the northeast, Lovono in the west, Tanema in the south [Fig. 2]. These three languages were vibrant in 1834 when Gaimard, a French naturalist, wrote down the first wordlists in Vanikoro languages. (He called the three languages Tanéanou [Teanu], Vanikoro [Lovono], and Tanema).

During the 20th century, the latter two languages became almost extinct, replaced by Teanu. In 2012, Lovono was surviving with only 4 speakers, and Tanema with only one. In 2021, all the Lovono speakers had passed away, resulting in the language becoming extinct.

During my fieldwork trips in Vanikoro (2005, 2012), I collected linguistic data on these three languages.

|

| Fig. 2 - Toponymic map of Vanikoro, showing the location of its three ancient tribes. – (by A. François) |

Teanu, Lovono and Tanema, the three indigenous languages of Vanikoro, are all Oceanic: they thus belong to the vast Austronesian family that covers most islands in the Pacific.

The Temotu archipelago where Vanikoro lies was initially settled about 3200 years ago by people of the “Lapita” culture (Pawley 2009; Green 2010). The language spoken by these Austronesian navigators was most likely Proto-Oceanic itself, the shared ancestor of all ≈500 Oceanic languages. (In this dictionary, most etymologies will refer to Proto-Oceanic or “POc”.)

It is likely that Proto-Vanikoro, the ancestor of the three Vanikoro languages (François 2009), developed in situ following the initial settlement of the island.

Due to their common ancestry, the three languages of Vanikoro clearly show some general similarities. And yet, what is most striking is the degree of dissimilarity they acquired during the three millennia of human settlement. Whether this is due to tribal isolation, or to processes of spontaneous differentiation, the three languages have long lost mutual intelligibility (see François 2009).

The following two examples illustrate how different the three languages of Vanikoro have become in their lexical forms; and yet, they remain closely similar in their grammatical structures.

| (1) | |||||||||

| Teanu | En' | na | dameliko | tae, | ene | na | ka | mwaliko | pine. |

| Lovono | Ngan' | da | apali | taie, | ngan' | da | ga | lamuka | pwene. |

| Tanema | Nana | kana | uneida | eia, | nana | kana | mo | anuka | bwau. |

| 1sg | prox | child | neg | 1sg | prox | pft | person | big | |

| ‘I'm not a child, I'm an adult now!’ | |||||||||

| (2) | |||||||||

| Teanu | Pi-ka | vele? | – Kupa | pi-te | ne | sekele | iupa, | pi-wowo | none. |

| Lovono | Nupe-mage | mene? | – Gamitu | nupe-lu | ne | amenonga | iemitore, | nupe-ngoa | nane. |

| Tanema | Ti-loma | vane? | – Gamuto | tei-o | ini | vasangola | akegamuto, | ti-oa | bauva. |

| 2pl:R-come | where | 1e:pl | 1e:pl:R-stay | loc | garden | poss:1e:pl | 1e:pl:R-plant | yam | |

| ‘Where are y'all coming from? – We were in our garden, we were planting yams.’ | |||||||||

For each entry in my Teanu dictionary, I also indicate – whenever I have them – the lexical equivalents in the island's two moribund languages. Lovono has 537 headwords and Tanema 564, covering respectively 37% and 39% of Teanu entries.

These forms can be quite instructive for the historical linguist wishing to compare the three languages of Vanikoro, and reconstruct their history from their Proto-Oceanic ancestor. Words from Lovono and Tanema are indispensable in reconstructing “Proto-Vanikoro”, the shared ancestor of these three languages. The meaning of Lovono and Tanema words can safely be assumed to be identical to those of Teanu: this isomorphism is indeed very strong on the island (François 2009).

Finally, besides its indigenous Melanesian population, Vanikoro is also home to a Polynesian community, whose ancestors have been colonising the southern shore since at least the 16th century. Their homeland is Tikopia (the easternmost island of the Solomon archipelago), and their language is Tikopia or Fakatikopia – also an Oceanic language, but from the Polynesian (“outlier”) branch.

Teanu in its regional context⇫¶

Phylogenetic affiliation⇫¶

If we set aside Fakatikopia, the two neighbouring islands Vanikoro and Utupua, combined, are home to six indigenous languages – three on each island. The genealogical links between these six languages have been observed for a long time: together, they are understood to form a single subgroup called “Utupua–Vanikoro”, once known as as “Eastern Outer Islands” (Tryon & Hackman 1983, Tryon 1994).

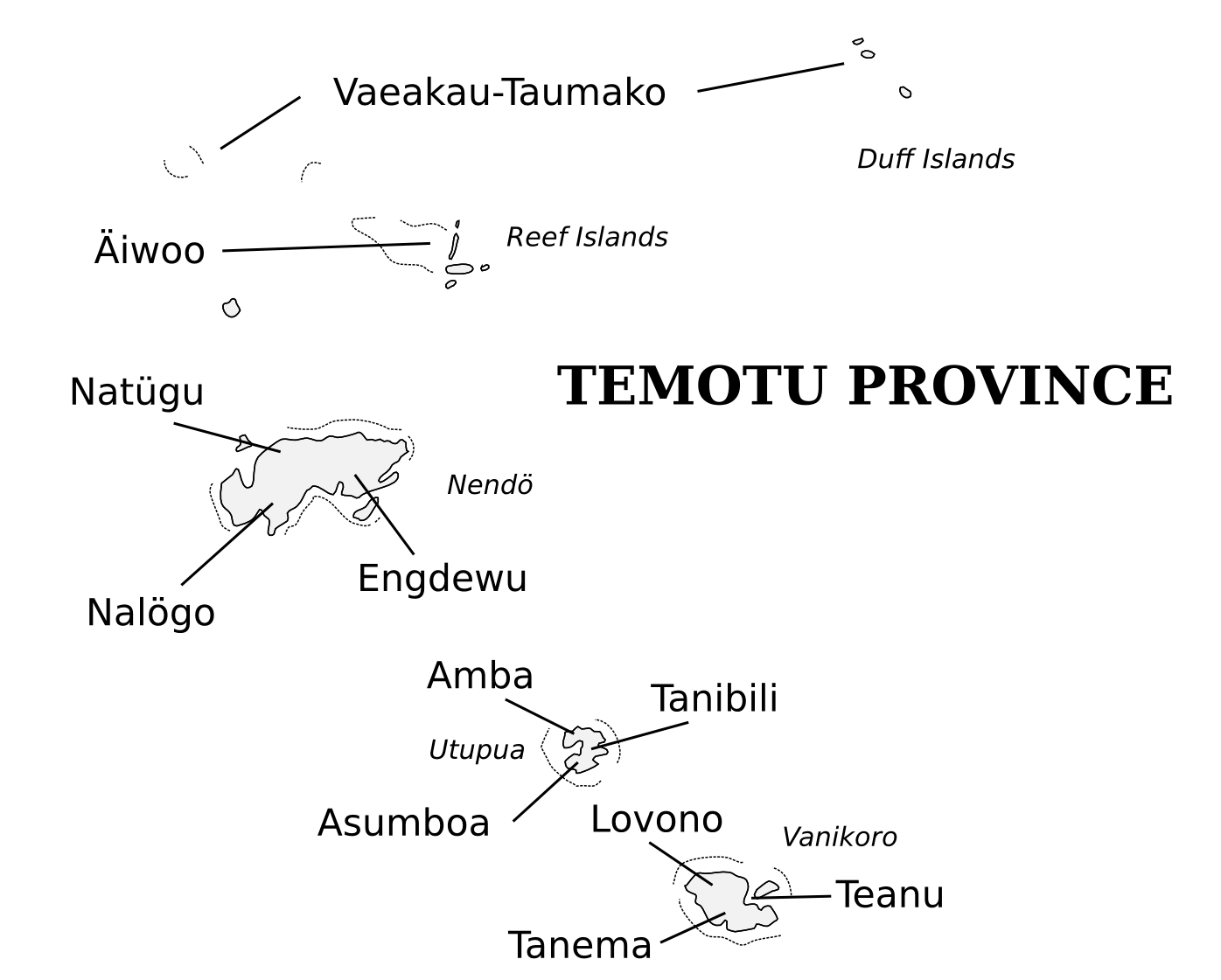

More recent research has proposed to connect the latter group with the Reefs ‒ Santa Cruz languages under a tentative “Temotu” branch of Oceanic (Ross & Næss 2007) – see the entry Temotu on Glottolog. That branch includes about ten languages, all located in the province of the same name [see Fig. 3]. The precise historical development of the Temotu subgroup remains matter for further research (see Lackey & Boerger 2021).

|

| Fig. 3 - The languages of Temotu province (eastern Solomons). Except for Tikopia (east of the map) and Vaeakau-Taumako which are Polynesian, all other languages here belong to the “Temotu” subgroup of Oceanic. Source: NordNordWest and Stefano Coretta, Map of Temotu languages (2015), Wikimedia Commons. Based on publications by Ethnologue, Boerger (2007), and François (2009). |

Language contact⇫¶

Vanikoro people always had contacts – both trade exchanges and intermarriage – with the nearby island of Utupua; and to a lesser extent, with other islands of the Temotu region: Nendö (Santa Cruz), the Reefs – as well as Polynesian communities from Tikopia and Vaeakau-Taumako (see Tryon 1994).

The centuries of contact with Polynesian languages manifest themselves in Teanu through many borrowings: 59 exactly in this dictionary (=4 percent of the Teanu lexicon). These include many nouns of artifacts; these are often recognizable by their initial syllable te or to, which takes its source in the Polynesian article te (temotu ‘islet’; tepuke ‘sailing canoe’; toloto ‘lagoon’; tomona ‘pudding’…). Outside of nouns, Polynesian loans also include the grammatical marker of the prohibitive etapu ‘don't!’, derived from Polyn. tapu ‘sacred, taboo’.

Contact with other islands of the Temotu region has left very few or no linguistic traces – at least none that are obvious in the present state of our knowledge.

Looking further afield, Vanikoro is located only 150 km from the Torres islands of northern Vanuatu. The extreme linguistic difference between Vanikoro languages on the one hand, and those of the Torres & Banks islands on the other, suggests that there has been no in-depth contacts between the two regions.

That said, the myth of the “Tamate” spirits tells us how certain dancing headdresses were once borrowed from northern Vanuatu people – perhaps due to a fortuitous encounter [read the myth here]. The word Tamate indeed means ‘spirit; ritual headdress’ in Mota, one of the languages of the Banks islands (Ivens 1931, Vienne 1996). In total, Teanu has five words that were borrowed from Mota (Tamate ‘spirit represented in dances’; marama ‘world’; tapepa ‘present’; totokale ‘picture’; wolowolo ‘a cross’). These may have entered the Teanu language at the end of the 19th century, when Mota had been chosen by the Melanesian Mission as the language of Christianization for this part of Melanesia.

|

| Fig. 4 - The dance of the Tamate spirits, a tradition ultimately borrowed from Vanuatu. |

Finally, current generations are also experiencing modern life, particularly in the towns of Lata and in the capital Honiara. In urban contexts, the pressure is high to replace indigenous languages such as Teanu with the country's national language Solomon Islands Pijin – an English-based creole that emerged during colonial times. All speakers of Teanu are bilingual in Pijin, and some loanwords from English actually enter Teanu through Pijin.

All in all, about 7.1% of the Teanu lexicon consists of identifiable borrowings: 59 words borrowed from Polynesian, 19 from Solomons Pijin or English, 5 words from Mota in Vanuatu. As for the native lexicon, it proves quite original among other Oceanic languages: only 13.6% of entries can be traced back to Proto-Oceanic roots, while 79% of the lexicon has unclear origins. These innovative words probably result from three millennia of language-internal renewal of the lexicon – perhaps encouraged by a trend towards lexical differentiation (François 2009). The vocabulary of Vanikoro languages also shows extreme dissimilarities with other languages of the area (whether Utupua, Nendö or the Reefs), even though they supposedly belong to the same “Temotu” subgroup of Oceanic.

Methodology and data sources⇫¶

When I began studying it, Teanu was known mostly through wordlists (Gaimard 1834, Tryon & Hackmann 1983), and from a grammatical sketch (Tryon 2002).

Due to its difficult access, I've had only two occasions to visit Vanikoro. One was an archaeological expedition in April-May 2005, organized around the fate of French navigator Jean François de Lapérouse (Laperusi in Teanu), who had perished on the island in 1788. My role in that multidisciplinary project was to document the memory of that early encounter which is still vivid in the islanders’ oral tradition (François 2008); for that purpose, I first needed to familiarize myself with the island's indigenous languages.

My second trip was in 2012, with a group of geologists who took me with them for a brief visit to the island; I took that opportunity to collect more data on the island's two moribund languages Lovono and Tanema. To these two short stays, I was able to add a couple encounters with Teanu speakers – in Paris in 2008, in Honiara in 2017; and recently, regular contact with speakers through social media.

Altogether, my linguistic exposure to the language of Teanu was about 29 days in total. But thanks to my knowledge of nearby Vanuatu languages, and to a linguistic questionnaire I had designed (François 2019), I was able to speak and understand Teanu early enough to hold conversations and record naturalistic samples of the language.

My methodology in the field combined language learning, targeted elicitation, and the recording of spontaneous speech in the form of conversations or narratives. Out of the 73 items I recorded in Teanu, 43 were narratives; I transcribed 22 of these with the help of native speakers, yielding a digital corpus of 18,800 words. Among those transcribed texts, several are displayed online, in open access (Pangloss Collection, CNRS). The same archive hosts the valuable recordings I made in Lovono and in Tanema.

This dictionary⇫¶

This bilingual Teanu dictionary is based on my corpus of texts, conversations, elicited data, and immersive fieldwork.

It contains about 1900 entries in total, 2800 sense definitions, and 2800 example sentences.

While the present Dictionaria edition includes all my lexical data, interested readers can find the same data under a different presentation, on tiny.cc/Vanikoro-dict.

Special features⇫¶

This dictionary analyzes the words and phrases of the Teanu language, providing definitions in English, together with grammatical comments whenever necessary. It highlights the polysemy of many words, and illustrates each sense with example sentences. Most of these examples are taken from my text corpus. In fact, some provide a DOI link to hear the sentence in its original context: e.g. the entry ngiro ‘wind’ has examples linking to original texts, such as doi:Pangloss-0003352#S106 or doi:Pangloss-0003351#S16.

The present work pays attention not just to language and grammar, but also to culture and society. Many entries come with photographs and/or encyclopedic notes: see, for example, entries tolosai 'loincloth', savene 'valuable mat', jokoro 'bamboo', kolokolo 'breast plate', viavia mamdeuko 'feather money'…

Entries usually feature a broad array of cross-references to other words: heterosemes (see § Lexical flexibility); antonyms; synonyms; subentries and other derived phrases; and more generally, any other words connected one way or the other. A few dozen entries even provide a whole set of links for a given lexical domain – for example:

-

the entry for 'fire' iawo has a detailed list of vocabulary related to fire ('light a fire', 'flame', 'ashes', 'charcoal'…);

-

kuo 'canoe' connects to all the technical terms for canoe parts ('hull', 'outrigger', 'boom', 'sail', 'bow' and 'stern'…);

-

uie luro 'coconut palm' links to various objects traditionally woven out of coconut leaves ('mat', 'semi-mat', 'basket', 'fan'…);

-

ngiro 'wind' lists the names of all winds, and includes a wind map;

-

revo 'sea' brings together many words from the lexicon of the sea;

-

vilo 'tree' cites various words from the semantic field of trees ('branch', 'leaves', 'to plant', 'to grow');

-

nengele moe 'house parts' has a list of all the elements of carpentry;

-

moro 'day' lists the words referring to moments of the day;

-

and so on and so forth.

Semantic fields⇫¶

Many entries are assigned some semantic fields. The following table provides a key to the abbreviations:

Table 1 – Semantic fields used in this dictionary

| Abbr | Semantic field | Abbr | Semantic field |

|---|---|---|---|

Anat |

Anatomy |

Ins |

Insect |

Archi |

Architecture |

Kin |

Kinship |

Artf |

Artifact |

Mod |

Modern society |

Astr |

Astronomy |

Mus |

Musical arts |

Bot |

Botany |

Myth |

Mythology |

Christ |

Christianity |

Naut |

Navigation, seafaring |

Disc |

Discourse, Pragmatics |

Ornith |

Birds & ornithology |

Ethn |

Anthropological, cultural interest |

Sea |

Sea, ocean |

Fish |

Fish & ichthyology |

Spirit |

Spirits, religion |

Geo |

Geography, toponymy |

Techn |

Technical vocabulary |

Gram |

Grammar |

Zool |

Zoology: misc. animals |

Basics of the grammar⇫¶

An overview of the grammar of Teanu can be found in Tryon (2002) and in François (2009); a more complete grammar is in preparation. The present summary will only highlight a few points that can help the reader make the most of this dictionary.

Orthography⇫¶

All forms in this dictionary are transcribed in the language's orthography, accompanied by their phonetic transcription. Teanu's alphabetical order is:

Each of these letters or digraphs corresponds to one phoneme in the language.

Phonology⇫¶

Teanu has 19 phonemic consonants. Table 2 lists the phonemes themselves (using IPA); and in brackets, the orthographic symbol. For example, letter ‹j› in the orthography encodes the prenasalized palatal stop /ᶮɟ/ .

Table 2 – The 19 phonemic consonants of Teanu

| Labio- velarized |

Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voiceless stop | pʷ ‹pw› | p ‹p› | t ‹t› | k ‹k› | ||

| Prenasalized stop | ᵐbʷ ‹bw› | ᵐb ‹b› | ⁿd ‹d› | ᶮɟ ‹j› | ᵑg ‹g› | |

| Fricative | v [v,f] ‹v› | s ‹s› | ||||

| Nasal | mʷ ‹mw› | m ‹m› | n ‹n› | ɲ ‹ñ› | ŋ ‹ng› | |

| Lateral | l ‹l› | |||||

| Rhotic | r ‹r› | |||||

| Approximant | w ‹w› |

-

The phoneme /v/ can surface as voiced [v], but also as voiceless [f], especially word-initially: e.g. vede [feⁿde] ‘pandanus’; evele [evele] ~ [efele] ‘falcon’.

-

There is no phonemic palatal glide y [j]: it only exists as an allophone of /i/ before another vowel: e.g. iebe [i.e.ᵐbe] ~ [je.ᵐbe] ‘besom, broom’.

Teanu has 5 vowels, all short.

Table 3 – The 5 vowels of Teanu

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i ‹i› | u ‹u› |

| Mid | e ‹e› | o ‹e› |

| Open | a ‹a› | |

Stress regularly hits the penultimate syllable of a phonological word:

- Teanu [teˈanu] 'Teanu'; abia [aˈᵐbia] 'many'; le-le [ˈlele] 'let's go!'; webwe [ˈweᵐbʷe] 'troca'; vesepiene [ˌfesepiˈene] 'word'; basakulumoe [ˌᵐbasakuluˈmoe] 'island'.

Phonotactics⇫¶

Teanu shows a preference for open syllables CV, and all words end in a vowel. However, consonant clusters are sometimes found word-internally (resulting historically from the syncope of a high vowel /i/ or /u/):

Table 4 – A sample of Teanu words, with or without consonant clusters

| meaning | orthog. | pronunc. | variant without syncope |

| ‘island’ | basakulumoe | [ᵐbasakulumoe] | |

| ‘taro’ | jebute | [ᶮɟeᵐbute] | |

| ‘a little’ | amjaka | [amᶮɟaka] | amijaka |

| ‘star’ | kanmoro | [kanmoro] | kanimoro |

| ‘male’ | mwalkote | [mʷalkote] | mwalikote |

| ‘men’s clubhouse’ | toplau | [toplau] | topulau |

| ‘swear’ | ~aptei | [aptei] | |

| ‘ritual pole in festivals’ | blateno | [ᵐblateno] | bulateno |

Word classes⇫¶

Every word can be assigned at least one class (or "syntactic category" or "part of speech"), based on its grammatical behaviour. Thus moe 'house' is a noun; aplaka 'small' is an adjective; ~aiae '(be) difficult' is an intransitive verb; ~ago 'shoot, spear' a transitive verb, etc. The rationale for each word class is explained in Table 5 below.

One of the characteristics of verbs is that they are bound forms, requiring a subject prefix: this is indicated with a tilde sign ~ before the radical. Thus ~abu 'go down' cannot appear on its own, it needs a prefix such as 3sg i-, yielding a citable form like i-abu [iaᵐbu] ‘he's going down’. In this dictionary, the phonetic transcription of verbs will thus add a prefix in brackets, like [(i·)aᵐbu].

When a given word governs a specific kind of complement, I indicate it between small angled brackets. This concerns the (direct) object of transitive verbs:

-

e.g. ~kidi: “pick ‹betel leaves, puluko› by pinching their stems”

-

~lu1: “scrape ‹tuber› or grate ‹coconut flesh›, with a bivalve shell or grater”.

The same symbol can be used when specifying the typical possessor of an obligatorily-possessed noun:

-

e.g. iula2: “rope of ‹s.th.› / chain of ‹ship›”

-

mengela: “top of ‹tree› / end of ‹s.th.› / piece of ‹wood›”.

Inventory of word classes⇫¶

Word-class membership is never based on the word's translation, but on its emic properties in Teanu. For example, while the word mimione 'dry' is an adjective, its antonym ~dobuo 'wet' is classified as a verb, because it behaves grammatically as a verb in Teanu – regardless of its English translation. Likewise, ~metei 'be shy' is categorized as a “reflexive verb”, because it is construed reflexively in the language.

Providing each word class with a full description and illustration would require a whole grammatical chapter, which would go beyond the present introduction. That said, the facts can be summarized in the form of definitions for each lexical category. Thus, Table 5 provides definitions for each of our 44 word classes.

Table 5 – The word classes used in this dictionary of Teanu

| Word class | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

adjective |

Property word that can modify directly a noun, or form a direct predicate. Does not take prefixes (unlike verbs). |

motoro |

adjective, transitive |

An adjective* requesting an extra argument (cf. Eng. fond of) |

votobo |

adverb |

Word or lexicalized phrase external to the predicate phrase (opp. postverb), and filling the function of adjunct. May appear after the predicate, or be topicalized. |

nga ne |

aspect |

Word or lexicalized phrase adjacent to the predicate (just before or after it) encoding semantic information on aspect. |

kata kape |

auxiliary |

Verb* specialized in the first slot of a serial verb construction, with semantic scope over the following verbs |

~tabo |

construction |

Lexicalized combination of words and morphemes with a non-compositional meaning, and featuring an open slot (opp. phrase*) |

mamote… tae |

coordinator |

Particle* linking two clauses in a coordinating construction |

ia ‘but’ |

deictic |

Phrase-final particle* used for deixis, either literal (spatial) or figurative (discourse deixis). Can be used as demonstrative modifying a noun, or as a deictic taking a whole clause as its scope. |

re ‘Distal deictic (over there)’ |

indefinite pronoun |

Word or lexicalized phrase heading a noun phrase, referring to a non-specific indefinite [e.g. Eng. anyone] |

ngele nga |

intensifier |

Word modifying a stative predicate (verb or adjective) to mark it as intense [cf. Eng. very] |

tadoe |

interjection |

Word or lexicalized phrase, performing a speech act on its own |

awis ‘thanks’ |

interrogative |

Word or lexicalized phrase carrying interrogative modality |

nganae ‘what’ |

linker |

Particle* linking a noun to another noun |

da ‘and (noun coordinator)’ |

locative |

Adverb* referring to a location in space or time. Can function as a topic or as an adjunct (outside the predicate phrase). |

tetake |

modal |

Word or lexicalized phrase, adjacent to the predicate (just before or after it) encoding semantic information on modality. |

nara |

noun |

Word that can head a referential phrase, can form a predicate, can be possessed. When possessed, ordinary nouns – labelled “noun”, opp. relational noun – take a possessive classifier (ie, we). |

kuo ‘canoe’ |

noun, kinship |

Noun* referring to a kin relation, obligatorily possessed by means of the kinship classifier one. |

leka ‘cross-cousin’ |

noun, relational |

Noun* obligatorily possessed, through a direct construction ({N₁ N₂} or {N₁ Pron}) instead of a classifier. Includes body parts, some meronyms, some clothes, some spatial relations (‘inside’ etc.). |

enga ‘name (of)’ |

numeral |

Word indicating cardinal number. May head an argument phrase; may modify a (noun) head; may form a predicate on its own. |

tilu ‘two’ |

particle |

Non-affixal morpheme, employed as a satellite to a lexeme or phrase, either before or after it. (Some subtypes of particles are assigned a word class of their own.) |

tae ‘Negation’ |

pers. pronoun |

Independent personal pronoun, used as topic, object, possessor, object of prepositions, subject of non-verbal predicates (opp. subject prefix). |

kaipa |

phrase |

Lexicalized combination of words and morphemes with a non-compositional meaning, and with no internal open slot (opp. construction*). |

ebele nga |

possessive |

Possessive linker or classifier, inflected for person and number. [see § Possessive marking] |

ono ‘your (food+): 2sg form of food classifier’ |

postverb |

Word following immediately a verb (or another predicate head) to modify it. Internal to the predicate phrase (opp. adverb). Uninflected (opp. 2nd verb). |

ate |

postverb, transitive |

A non-affixal applicative — i.e. a postverb* that introduces an extra argument. Internal to the predicate phrase (opp. preposition). |

rema |

predicative |

Word or lexicalized phrase used as a predicate head, and unable to head a referential phrase. Uninflected (opp. verb). |

awoiu |

prefix |

Prefix used in lexical derivation. |

kwa- |

preposition |

Word taking a noun phrase as its argument, and forming with it an adjunct (cf. adverb*). |

teve ‘towards; by; with’ |

proper noun |

Proper name of person, god, or wind. (For place names, cf. toponym*) |

Banie ‘a god’s name’ |

quantifier |

Word providing information on the quantity of a referent. Either found inside the noun phrase, or floating. |

kula ‘some’ |

serial vb, intr. |

Lexicalized combination of verbs in a serial construction, behaving as globally monovalent (intransitive). |

~abu ~te |

serial vb, trans. |

Lexicalized combination of verbs in a serial construction, behaving globally as bi‑ or trivalent. |

~la ~teli |

subject prefix |

Prefix taken by verbs, inflecting for mood [Realis vs. Irrealis], person, and number. Non-singular prefixes contrast “Collocutive” (1incl, 3rd person) vs. “Dislocutive” (1excl, 2nd person) – see § Pronominal indexing. |

pe- ‘Dislocutive irrealis (Irrealis:1excl:pl / Irrealis:2pl)’ |

subordinator |

Word encoding a relationship of dependency between two clauses. |

nga |

suffix |

Suffix used in lexical derivation. |

‑ene ‘suffix for ordinal numerals’ |

toponym |

Proper name for a specific place. Patterns grammatically like a locative*. |

Tetevo ‘Utupua’ |

verb, intransitive |

Verb (with subject prefix) used with no object. Includes stative verbs if they take a subject prefix (opp. adjective*). |

~epele |

verb, oblique transitive |

Verb (with subject prefix) subcategorizing for a second argument that is treated as oblique, i.e. introduced by a preposition*. |

~bi ‘fan [at] s.th.’ |

verb, reflexive |

Verb (with subject prefix), used with an object that must co-refer with the subject. |

~metei |

verb, transitive |

Verb (with subject prefix), used with an object. |

~avi ‘pick up’ |

verb-object idiom |

Lexicalized phrase* consisting of a transitive verb plus its object, often with non-compositional meaning. |

~teli utele |

2nd verb, intrans. |

Intransitive verb used only as a second verb in a serial construction, or showing special behaviour (syntactic or semantic) when found in that position. |

~ejau |

2nd verb, trans. |

Transitive verb used only as a second verb in a serial construction, or showing special behaviour (syntactic or semantic) when found in that position. |

~katau ‘follow → do accordingly…’ |

Lexical flexibility⇫¶

In my syntactic analysis (explained in François 2017), a given word can show lexical flexibility, by being assigned several word classes – similar to English [n.] snow, [v.] snow. Rather than calling them "homophones", I propose to analyze such examples (snow, snow) as "heterosemes" – i.e. identical forms linked by a semantic relationship of "heterosemy" (or conversion), and showing different grammatical behaviour. Thus the Eng. noun snow and the verb snow would not be homophones in English, but “heterosemes”.

While homophones are treated as separate entries, my original dictionary treats all heterosemes under a single entry, which is split into separate lexical sections: e.g. biouro ‹a› [adj] 'long' – ‹b› [n] 'length' – ‹c› [adv] 'at length', etc. Yet for technical reasons, the present Dictionaria platform had to treat all heterosemes (i.e. {form / word class} pairing) as separate entries, as though they were homophones: e.g. biouro 1, biouro 2, biouro 3. In such a case, these separate entries are mutually linked with a label "heterosemes" in the cross-reference section (Related entries) under each entry.

When a verb is labile, i.e. is used sometimes as intransitive and sometimes as transitive, this is treated as a case of heterosemy, in the form of separate entries. For example, this dictionary contrasts between ~tobo 1 [v.intr.] ‘poke out’; ~tobo 2 [v.tr.] ‘poke ‹s.th., s.o.›’; and ~tobo 3 [v. oblique tr.] ‘measure, indicate [s.th., ñe+Obj.]’.

Pronominal indexing⇫¶

The personal pronouns of Teanu distinguish three numbers: singular, dual, plural. They also strictly encode the contrast between 'inclusive we' {you + me + others] and 'exclusive we' {me + others (excluding you)}. Thus the pronoun kia "1inclusive: dual" means 'you & me', whereas keba "1exclusive: dual" will read as 'one person (other than you) + myself', i.e. 'me & him/her'.

Free pronouns can serve as subject, object of transitive verbs, object of prepositions. In addition, all verbs require a subject prefix, which distinguishes realis vs. irrealis mood.

Table 6 – Pronominal forms in Teanu

| free pronouns | subject prefixes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| realis | irrealis | |||

| sing | 1 | ene | ni- | ne- |

| 2 | eo | a- | u- | |

| 3 | ini | i- | i- | |

| dual | 1 incl. | kia | la- | la- |

| 1 excl. | keba | ba- | ba- | |

| 2 | kela | ba- | ba- | |

| 3 | da | la- | la- | |

| plural | 1 incl. | kiapa | li- | le- |

| 1 excl. | kupa | pi- | pe- | |

| 2 | kaipa | pi- | pe- | |

| 3 | dapa | li- | le- | |

| Generic | idi | |||

The following examples illustrate the basic morphosyntax of personal indexes – both free pronouns and subject prefixes:

| (3) | Ene | ka | ni‑romo | eo | ia | eo | mamote | a‑romo | ene | tae. |

| 1sg | pft | 1s:R-see | 2sg | but | 2sg | still | 2s:rl‑see | 1sg | neg | |

| ‘I’ve seen you, but you haven’t seen me yet.’ | ||||||||||

| (4) | Da | kape | la-te | teve | kiapa. |

| 3du | fut | colloc[3]:du‑stay | with | 1inc:pl | |

| ‘They (two) will stay with us.’ | |||||

Collocutive vs. dislocutive prefixes⇫¶

The list of subject prefixes shows a typologically unusual pattern. For each non-singular number, the language co-expresses:

-

3rd person = 1st inclusive prefixes (dual la-, plural li- / le-)

→ “Collocutive” category -

1 exclusive = 2nd person prefixes (dual ba-, plural pi- / pe-)

→ “Dislocutive” category

François (2014) coined new terms for these two emic categories. The semantic divide is evidently based on whether a given prefix treats the speaker (‘I’) and the addressee (‘you’) together or not:

-

“Collocutive” pronouns treat speaker and addressee as part of the same group (i.e. as both included in the grammatical subject in case of 1st inclusive reading; or both excluded in case of 3rd person);

-

“Dislocutive” pronouns oppose the group built around the speaker vs. the one built around the addressee.

As far as our dictionary is concerned, this terminological proposal only affects the lexical entries for the subject prefixes themselves, and is supplemented by explanations: thus, pe- is glossed “irrealis subject prefix for Dislocutive plural: i.e. 1st exclusive or 2nd person”. Other entries do not make reference to these two concepts.

Generic person⇫¶

Finally, Teanu has a special pronoun idi for “generic” reference (François 2014). This generic pronoun, similar to French on, agrees with the “Collocutive” plural prefix on the verb.

| (5) | Tamate | li-romo | wako | ia | idi | li-madau. |

| mask | colloc[gnrc]:pl‑see | good | but | gnrc | colloc[gnrc]:pl‑fear | |

| ‘The dancing masks were beautiful, but scary.’ [liter. ‘One sees them beautiful, but one is scared.’] |

||||||

Generic indexes are found not only in the paradigm of independent pronouns [Table 6], but also in the inflection of possessive classifiers [Table 7 below] – e.g. iaidi ‘Kinship possession, Generic possessor’:

| (6) | Lek’ | iaidi, | idi | pe | li-romo | idi | tae. |

| cousin | kin:gnrc | gnrc | rel | colloc[gnrc]:pl-see | gnrc | neg | |

| ‘Cousins must not look at each other.’ [liter. ‘One’s cousin(s) are people who must not look at one.’] |

|||||||

Possessive marking⇫¶

Types of nouns⇫¶

Teanu encodes adnominal possession in a pattern {Possessed + Possessor}. Nouns are divided along a grammatical split, regarding whether or not they require a possessor:

– Independent (~ intransitive ~ alienable) nouns:

the majority of nouns may occur without a possessor – e.g. moe 'house', kuo 'canoe'. (They are just labelled noun in this dictionary.) When they do take a possessor, it must be introduced using a possessive linker or classifier (see below).

– Dependent (~ transitive ~ inalienable ~relational) nouns:

about 115 nouns of Teanu are dependent nouns, which require an overt possessor. They are further divided into two subclasses, based on how they encode their possessor:

- kinship nouns – e.g. uku 'father-in-law (of s.o.)'

→ uk’ one ‘my father-in-law’, with kinship classifier one - relational nouns – e.g. ma 'arm, hand (of s.o.)'; enga 'name (of s.o.)',

→ enga ene ‘my name’, with a direct construction involving the 1sg free pronoun ene.

Encoding of the possessor⇫¶

When the possessor is not a noun but a pronoun, it is encoded by a “personal possessive”. But the form taken by that personal possessive will depend on the exact meaning of the possessive relationship. Most of the time, this amounts to assigning the possessed noun to a certain possessive class, grounded in semantics:

-

body parts and other relational nouns:

= {n.rel + free pronoun} (see Table 6)

→ visibaele ene ‘my knee’; enga ini ‘her name’; vilisa dapa ‘their clothes’;

→ awa (Ø) Teliki ‘Teliki's desire’. -

kinship nouns

= {n.kin + KIN possessive}

→ uk' one ‘my father-in-law’; et’ iape ‘his/her mother’; gi’ adapa ‘their uncle’;

→ ai’ ie Teliki ‘Teliki's father’. -

food + drink + tools + certain valuable notions (e.g. language, culture)

= {n + FOOD possessive}

→ buioe enaka ‘my betelnut’; laro ape ‘his/her drinking coconut’; piene adapa ‘their language’;

→ okoro we Teliki ‘Teliki's knife’. -

other possessions

= {n + GENERAL possessive}

→ moe ’none ‘my house’; emel’ iape ‘his wife’; kulumoe iadapa ‘their village’

→ men’ ie Teliki ‘Teliki's child’.

Table 7 – Personal possessives in Teanu

| KIN poss. | FOOD poss. | GENERAL poss. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sing | 1 | one | enaka | enone |

| 2 | – | ono | iono | |

| 3 | iape | ape | iape | |

| dual | 1 incl. | akia | akia | iakia |

| 1 excl. | aba | aba | iaba | |

| 2 | amela | amela | iamela | |

| 3 | ada | ada | iada | |

| plural | 1 incl. | akapa | akapa | iakapa |

| 1 excl. | upa | upa | iupa | |

| 2 | aipa | aipa | iaipa | |

| 3 | adapa | adapa | iadapa | |

| Generic | iaidi | aidi | iaidi | |

| +N | ie | we | ie | |

A text in Teanu⇫¶

A short text can serve as a sample to illustrate how sentences work in Teanu. Interlinear (word-to-word) glosses can help the reader connect these sentences with the grammar sketch provided on this page.

I collected the following text in May 2005, in the village of Temwo, from Chief †Bartholomew Alungo.

Chief Alungo explained how young boys were traditionally initiated in the Boys’ Club house (Toplau mwa gete). In a way reminiscent of a boarding school, teenage boys would live in that house for several years. This formative time constituted a transition between childhood ‒ when a young boy lived with his parents ‒ and adulthood ‒ when he'd finally build his own house.

| 1. | Toplau | mwa | gete, | daviñevi | li-koie | tae, | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| men’s.club | house.of | young.boys | women | 3p:rl‑enter | neg | ||

| “The Boys’ club house is a place where women cannot go; | |||||||

| 2. | dapa | gete | ñoko | li-ovei | pe | li-te | ene. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pl | young.boys | only | 3p:rl‑know | sub | 3p:rl-stay | loc:anaph | |

| only young men are able to stay inside. | |||||||

| 3. | Noma, | po | apali | i-maili | i-ven’ | i-ka, | po | mamote | aplaka, |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| before | sub | child | 3s-grow | 3s-go.up | 3s‑come | sub | still | small | |

| Traditionally, as a boy grows up – well, as long as he is still a child, | |||||||||

| 4. | i-te | tev’ | ai’ | iape | me | et’ | iape | ne | moe | iadapa. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3s‑stay | with | father | kin:3s | and | mother | kin:3s | loc | house | poss:3pl | |

| he’ll live with his parents, in their house. | ||||||||||

| 5. | Bwara | i-le | pine, | po | ra | i-le | ini | mwatagete, |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| maybe | 3s‑go | big | sub | until | 3s‑go | 3s | young.boy | |

| But when he grows up to be a teenager, | ||||||||

| 6. | ai’ | iape | kape | i-ejau | aña | none | mijaka |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| father | kin:3s | irr | 3s‑make | bit | food | little | |

| his father will prepare a little ceremony, | |||||||

| 7. | me | kape | i-la | men’ | iape | i-koioi | ne | toplau. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| purp | irr | 3s‑take | son | kin:3s | 3s‑introduce | loc | men’s.club | |

| so as to introduce his son into the men’s club. | ||||||||

| 8. | Toplau | pon, | uña | teliki | samame | dapa | wopine | li-kilasi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| men’s.club | topic | pl | chief | with | pl | great.men | 3p:rl‑address | |

| In that club, chiefs and elders give speeches, | ||||||||

| 9. | we | li-waivo | uña | dapa | gete | ñe | telepakau | akapa. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| or | 3p:rl‑teach | pl | pl | young.boys | obl | law | food:1in.pl | |

| they teach youngsters about our customary laws. | ||||||||

| 10. | Idi | pe | li-te | ne | toplau | pe | i-wene | i-wene, |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gnrc | rel | 3p:rl‑stay | loc | men’s.club | rel | 3s‑go.on | 3s‑go.on | |

| Those who stay in the club for a long time, | ||||||||

| 11. | ebieve | kape | i-pu | i-sali. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | irr | 3s‑run | 3s‑drop | ||||

| entire years will go by [before they can leave]. | |||||||

| 12. | Mwatagete | kape | i-te | ne | toplau, | ra | ra |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| young.boy | irr | 3s‑stay | loc | men’s.club | dur | dur | |

| A young boy will live in the men’s club for a long time, | |||||||

| 13. | basavono | po | kape | ai’ | iape | i-wasu | emele | i-min’ | ini |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| moment | sub | irr | father | kin:3s | 3s‑fix | woman | 3s‑give | 3s | |

| until his father arranges him a wife. | |||||||||

| 14. | ka | i-ke | mina | toplau | pon, | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| and | 3s‑exit | from | men’s.club | dem2 | |||

| That is when he will come out of the men’s club, | |||||||

| 15. | pe | kape | i-vo | moe | iape | ini | ñoko | i-te | ñei. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rel | irr | 3s‑build | house | poss:3s | 3s | only | 3s‑stay | obl:anaph | |

| ready to build his own house, where he can live by himself.” | |||||||||

Acknowledgments⇫¶

It is not possible to list here the many Teanu speakers who have taught me words in their languages, and helped my progress along the years. To name but a few, my warmest thanks go to Ben Tua Apilaka, Stanley Wako Repwamu, Teka Repwamu, Janet Udeu, Ruben Ubi, Mosten Cook, David Tate, Mak Lakule, Tere Brad Alungo, Eddy Pae, Steve Koro, Ezekiel Prians Tamoa.

I am also highly indebted to the many men and women who told me their countless stories or sang me their songs in Teanu: Teliki Thomas (†2009), Faithful Bila (†2010), Daniel Bakap (†2014), Teliki James Cook Pae (†2014), Bartholomew Alungo (†2020), Teliki Ben Tua Pine (†2010), Willy Usao (†2017), Marion Laki (†), Mary Laulei (†), Mofet Bwana, Wolta Simevio.

Finally, I am grateful to several scholars who, over the years, took time to discuss with me various aspects of my language data from Vanikoro – including Even Hovdhaugen (†), Darrell Tryon (†), Piet Lincoln, Andrew Pawley, Malcolm Ross, Åshild Næss, Brenda Boerger, Bill Palmer, Siva Kalyan, and Ulrike Mosel – to name but a few. Thanks also are due to the team of Dictionaria, whose advice improved the quality of this dictionary considerably: Iren Hartmann, Johannes Englisch, Barbara Stiebels, and Martin Haspelmath.

References⇫¶

The following selected publications present various aspects of the Teanu language and culture:

- François, Alexandre. 2005. A toponymic map of Vanikoro. Electronic publication. Paris: CNRS.

- François, Alexandre. 2008. Mystère des langues, magie des légendes. In Le mystère Lapérouse ou le rêve inachevé d’un roi, edited by Association Salomon. Paris: de Conti, Musée national de la Marine. 230-233.

- François, Alexandre. 2009. The languages of Vanikoro: Three lexicons and one grammar. In Bethwyn Evans (ed). Discovering history through language: Papers in honour of Malcolm Ross. Pacific Linguistics 605. Canberra: Australian National University. 103-126.

- François, Alexandre. 2014. Person syncretism and impersonal reference in Vanikoro languages. Paper read at Syntax of the World's Languages (SWL6), Università di Pavia.

- Gaimard, Joseph Paul. 1834. Vocabulaires des idiomes des habitans de Vanikoro. In Jules Sébastien César Dumont d’Urville (ed.), Voyage de découvertes de l’Astrolabe, exécuté par ordre du Roi, pendant les années 1826-1827-1828-1829, sous le commandement de M. J. Dumont d’Urville, Capitaine de vaisseau — Philologie, 1:165‑74. Paris: Ministère de la Marine.

- Tryon, Darrell T. & Brian D. Hackman. 1983. Solomon Islands Languages: An Internal Classification (Pacific Linguistics no. 72). Canberra: Australian National University.

- Tryon, Darrell. 1994. Language contact and contact-induced language change in the Eastern Outer Islands, Solomon Islands. In Tom Dutton & Darrell Tryon (eds.), Language Contact and Change in the Austronesian World, 611–648. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Tryon, Darrell. 2002. Buma. In John Lynch, Malcolm Ross & Terry Crowley (eds), The Oceanic languages (Curzon Language Family Series 1), 573–586. London: Curzon.

- Tua, Benjamin & Peter C. Lincoln. 1979. Our Custom Way Vanikoro: The Custom Book. Auckland: University of Auckland. 34 pp.

Other references mentioned in this introduction:

- Boerger, Brenda H. 2007. Natqgu literacy: Capturing three domains for written language use. Language Documentation and Conservation. 1(2). 126–153.

- François, Alexandre. 2017. The economy of word classes in Hiw, Vanuatu: Grammatically flexible, lexically rigid. Studies in Language 41(2). 294–357.

- François, Alexandre. 2019. A proposal for conversational questionnaires. In Aimée Lahaussois & Marine Vuillermet (eds.), Methodological Tools for Linguistic Description and Typology. Special issue of Language Documentation & Conservation 16, 155-196.

- Green, Roger C. 2010. The Outer Eastern Islands of the Solomons: A puzzle for the holistic approach to the anthropology of history. In John Bowden, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, & Malcolm Ross (eds) A Journey through Austronesian and Papuan Linguistic and Cultural Space: Papers in Honour of Andrew K. Pawley, 207‑223. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- Ivens, W. G. 1931. The place of Vui and Tamate in the religion of Mota. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 61. 157–166.

- Lackey, William James & Brenda H. Boerger. 2021. Reexamining the phonological history of Oceanic’s Temotu subgroup. Oceanic Linguistics 60(2), Dec 2021. DOI: 10.1353/ol.2020.0029.

- Pawley, Andrew K. 2009. The role of the Solomon Islands in the first settlement of Remote Oceania: Bringing linguistic evidence to an archaeological debate. In Andrew K. Pawley & Alexander Adelaar (eds), Austronesian historical linguistics and culture history: A festschrift for Bob Blust, 515-540. Pacific Linguistics. Canberra.

- Ross, Malcolm & Åshild Næss. 2007. An Oceanic origin for Äiwoo, the language of the Reef Islands? Oceanic Linguistics 46 (2), Dec 2007: 456‑98. DOI: 10.1353/ol.2008.0003.

- Vienne, Bernard. 1996. Masked faces from the country of the Dead. In Joël Bonnemaison, Kirk Huffman, Christian Kaufmann & Darrell Tryon (eds.), Arts of Vanuatu, 234–246. Bathurst: Crawford House Press.

The reader may also want to access my audio corpus showcasing the oral literature of Teanu. My fieldwork recordings are all archived online, and available in open access:

- François, Alexandre. 2005–2012. Archive of audio recordings in the Teanu language. Pangloss collection. Paris: CNRS. (tiny.cc/AF-ark_Teanu).

You can also consult this dictionary of Teanu in a different presentation:

- François, Alexandre. 2021. A Teanu–English cultural dictionary (Electronic files). Paris: CNRS (tiny.cc/Vanikoro-dict).

Enjoy your browsing!

Alexandre François (CNRS–Lattice, Paris),

November 2021.

| Full Entry | Headword | Part of Speech | Meaning Description | Semantic Domain | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Text | Analyzed Text | Gloss | Translation | IGT |

|---|---|---|---|---|