Tseltal-Spanish multidialectal dictionary

This dictionary⇫¶

| Size | 8,109 entries; 321 images |

|---|---|

| Content | Lexical items of 20 dialects of Tseltal (Mayan language from Mexico, ISO 639:tzh; Glottolog code: tzel1254), with morphological segmentation, descriptions of meanings in Spanish and comparative concepts in English. Lemmas consist of uninflected stems, with the exception of phrasemes, which are inflected phrases or sentences. |

| Research assistants | Alberto Gómez Pérez, Alberto Gutiérrez Gómez, Ángela Lorena Cruz Gómez, Antonia Sántiz Girón, Catalina López Gómez, Jaime Pérez González, Juan López Intzín, Juan Méndez Girón, Manuel Vázquez Castellanos, María de Jesús Gómez Sánchez, Miguel Silvano Jiménez, Oscar Gregorio Cruz Méndez, Roberto Sántiz Gómez, Sebastián Aguilar Méndez, Tomás Gómez López |

| Photographs | Archive of the Tseltal Documentation Project |

| Purpose | Lexical documentation of Tseltal as a whole language through all its dialects. |

| Research context and funding | This dictionary is the revised electronic version of the paper dictionary Diccionario Multidialectal del Tseltal (Polian 2018); both dictionaries are part of the many outcomes of the Tseltal Documentation Project, hosted at CIESAS-Sureste, which was funded by ELDP/SOAS, CONACYT (Mexican National Council of Science and Technology), the INALI (Mexican National Indigenous Languages Institute) and the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. |

| Project Leader | Gilles Polian |

The language and its speakers⇫¶

Tseltal, previously spelled Tzeltal, is spoken in central and eastern Chiapas, a southeastern state of Mexico, by lightly less than half a million speakers. It is a western Mayan language, close to Chol (the language of classic Mayan inscriptions) and closest to Tsotsil (Tzotzil) (Kaufman 1972, Campbell 2017, Polian 2017).

Tseltal language is not immediately endangered as a whole thanks to its relatively large number of speakers (compared to most indigenous languages) and by the fact that many children still acquire it as their first language. However, Tseltal is threatened in the medium term. First of all, most speakers are now bilingual with Spanish and the linguistic transmission to new generations is globally on the decline, especially in urbanized places and their surroundings, where more and more children are now socialized primarily in Spanish. In some districts, such as Villa Las Rosas, Tseltal is on the verge of extinction, as only elders still speak it. In addition, the children that do acquire Tseltal learn an increasingly impoverished version of the language, as many native words fall into disuse, along with the traditional knowledges and ways of life that they were used to express. At the same time, Spanish is pervasively infiltrating the lexicon and the grammar, displacing native words and constructions and thus obstructing the genuine creativity of the language. Finally, there is almost no functional literacy, in spite of some progress being made in bilingual schooling, and the Mexican national context is still one of discrimination of indigenous languages and cultures.

Tseltal, like Mayan languages in general, is among the best described Amerindian languages. In addition to a few early colonial documents, in particular a good dictionary from the late 16th century (de Ara 1981), there has been a constant flow of publications since the mid-20th century. Published works include a reference grammar (Polian 2013a), dictionaries (Berlin and Kaufman 1977, Slocum et al. 1999), grammatical studies (Kaufman 1971, Polian 2007, Polian 2013b, Polian et al. 2015, Shklovsky 2012), dialectal and diachronic studies (Hopkins 1970, Kaufman 1972, Campbell 1987, Campbell 1988, Robertson 1987, Robertson 1992, Polian and Léonard 2009), acquisition studies (Brown 1998) and studies of semantic typology of space (Brown 1991, Brown 1994, Brown 2006, Levinson 1994, Brown and Levinson 1992, Brown and Levinson 1993, Polian and Bohnemeyer 2011), among others. Nevertheless, most studies focus on just a few dialects (Tenejapa, Oxchuc).

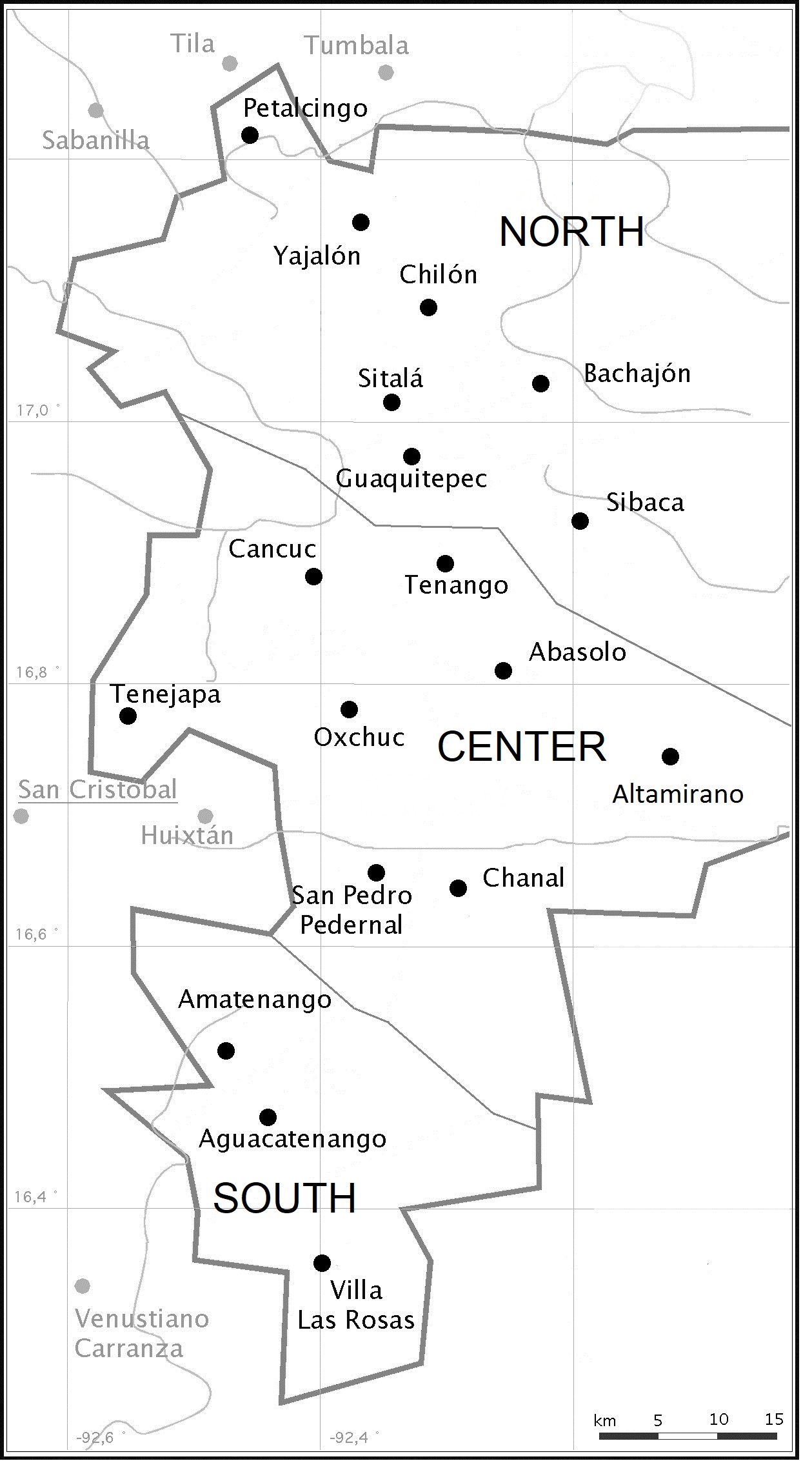

There are three broad dialect areas: North, Center and South, plus a dialectally heterogeneous oriental region, a place of recent migrations, which was not studied. Dialectal variation is only moderate, as it allows to some extent a fluid communication between speakers from different areas. This dictionary is multidialectal, as it covers eighteen places from all three areas, as represented in Map 1, along with the abbreviations used in this study. Note that references are also made to entire areas, through the corresponding abbreviation.

In the following list, the places where the lexicon was studied more thoroughly appear in boldface. In the other places, the lexicographic work was only partial.

Lexical coverage of the Multidialectal Tseltal Dictionary⇫¶

North:

- Petalcingo(PE)

- Yajalón (YA)

- Chilón (CHI)

- Bachajón (BA) [subdialects: San Sebastián (SS), San Jerónimo (SJ)]

- Sitalá (ST)

- Guaquitepec (GU)

- Sibakja’ (SB)

Center:

- Tenango (TG)

- Cancuc (CA)

- __Tenejapa __ (TP)

- Abasolo (AB)

- Oxchuc (OX)

- San Pedro Pedernal (SP)

- Chanal (CHA)

- Altamirano (AL)

South

- Amatenango (AM)

- Aguacatenango (AG)

- Villa Las Rosas (VR)

Others (not shown in Map 1):

- Oriental region (OR)

- Copanaguatla, extinct dialect from the 16th century (CO)

In the North, microdialectal information was included in the case of Bachajón, which covers two historically and socially well-defined parts: San Sebastián (SS) and San Jerónimo (SJ).

In the Center, the speech of Oxchuc and Chanal are practically identical (Chanal was founded by people from Oxchuc in historical times). Therefore, the dialectal category Oxchuc is meant to cover both Oxchuc and Chanal, unless it is indicated otherwise (e.g. chij in its second sense, ot).

As already mentioned, the oriental region, geographically known as “Cañadas” and “Selva” to the east of Map 1, was outside the lexicographical coverage. That area is dialectally heterogeneous, as it was populated by people from a great diversity of origins, speakers of indigenous languages (Tseltal and others) as well as monolinguals in Spanish. As a consequence, there is no oriental dialect of Tseltal as such. Nevertheless, a few data from villages of that region were included in the dictionary when it seemed relevant; those bear the abbreviation “OR”.

Finally, some data of comparative interest were included from de Ara 1981, the 16th century dictionary that describes the Tseltal spoken 500 years ago in Copanaguastla, a town to the south of Villa Las Rosas that disappeared in the 17th century. Those data are indicated by the abbreviation “CO”.

The dialectal information contained in this dictionary should be understood as the best approximation possible with the lexicographic work undertaken. It is not meant to be definitive or fully systematic: this is not a dialectal atlas.

Collaborators and source of the data⇫¶

Sixteen people contributed to the Tseltal-Spanish Multidialectal Dictionary (TSMD) as project collaborators, in addition to the coordinator and other occasional language consultants. Their participation varied from a couple of months to several years, from 2010 to 2017. Their names are listed below, alphabetically by first name in each category.

General lexicography (development, correction and edition of the multidialectal database):⇫¶

- Juan López Intzín (“Xuno”)

- Miguel Silvano Jiménez

- Oscar Gregorio Cruz Méndez

- Sebastián Aguilar Méndez

- Tomás Gómez López

Data collection by dialect:⇫¶

- Amatenango: Catalina López Gómez

- Bachajón: Alberto Gutiérrez Gómez, Miguel Silvano Jiménez

- Cancuc: Manuel Vázquez Castellanos

- Guaquitepec: Sebastián Aguilar Méndez

- Oxchuc: María de Jesús Gómez Sánchez, Roberto Sántiz Gómez

- Petalcingo: Alberto Gómez Pérez, Oscar Gregorio Cruz Méndez

- Tenango: Jaime Pérez González

- Tenejapa: Antonia Sántiz Girón, Juan López Intzín (Xuno), Juan Méndez Girón

- Villa Las Rosas:Tomás Gómez López

- Yajalón: Ángela Lorena Cruz Gómez

- Bionimy: Luis Malaret (Community College of Rhode Island)

This dictionary was developed as part of a larger project, the Tseltal Documentation Project (TDP), which started in 2006 in CIESAS-Sureste (San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico) under the coordination of Gilles Polian and which was still underway in 2017. The TDP provided a corpus of around 500 hours of transcribed audiovisual recordings in Tseltal for the lexicographic work. Those recordings include narratives, dialogues, spontaneous conversations, ritual speech, public discourse and songs; many of them are fully accessible at AILLA (http://www.ailla.utexas.org/) and ELAR (http://www.elar-archive.org/) under Gilles Polian’s deposits. Fieldwork was conducted in all the dialectal points shown on Map 1, more in some of them, less in others: most of the corpus concerns boldfaced place names of list (1) above. This corpus was one of the fundamental bases for the dictionary’s elaboration, since it allowed carrying out many searches for words, morphemes and phrases, as well as studying their semantics by context of use and their dialectal distribution. Many examples of the TSMD were extracted from the corpus, either directly when it was possible or through an edition process.

Many previous works, among which several dictionaries, were carefully examined at various stages of the TSMD project. Most important references, i.e. those that had a direct impact on this dictionary, are mentioned here:

- Brent Berlin and Terrence Kaufman worked together on a Tenejapa Tseltal-English dictionary, which was not published but has been accessible through various manuscript versions, and is registered in microfilm as Berlin and Kaufman 1977. This same database was later reworked and broadened as Brown and Levinson nd. Those two authors kindly shared their dictionary file with the TSMD team, for which we express to them our deep gratitude.

- The most complete Tseltal dictionary published up to now is Slocum et al. 1999, which is a Bachajón Tseltal-Spanish dictionary. It was elaborated in a community called Bahtsihbiltik, which belongs to the San Jerónimo sub-region (Bachajón (SJ)). The TSMD team frequently looked it up to confirm data from that dialect.

- The Public Education Office of Chiapas started publishing of several works on local indigenous languages some twenty years ago. In particular, two lexicographic works were taken into account: the Tenejapa Tseltal-Spanish dictionary (Zapata Guzmán 2002) and the multidialectal monolingual dictionary (Torres Sánchez et al. 2007).

- Kaufman 2003 was also carefully studied, for the large amount of Tseltal data it contains.

- From a very different perspective, the formerly mentioned dictionary Kaufman 2003 of a 16th-century Tseltal dialect was the object of many queries, although the task of linguistically processing all the information it contains is still incipient.

- Two linguistics Master’s theses with lexical information on certain Tseltal word classes were very useful: Sántiz Gómez 2010 on positionals and Pérez González 2012 on expressive predicates. Likewise, Gómez López 2017 is a PhD dissertation that consists of a dictionary of a particular Tseltal dialect: Villa Las Rosas. It was developed in parallel with the TSMD and both studies fed eachother to a great extent.

- The last dictionary that was often looked up for the TSMD project is the indispensable work of Laughlin 1975 on Zinacantán Tsotsil. Tsotsil and Tseltal are indeed so close to each other that they can be called sister languages, which makes that great dictionary, unique in its depth in Amerindian linguistics, so beneficial for Tseltal lexicography.

- In addition to dictionaries, other studies contain significant lexical information on particular semantic fields or word classes of Tseltal. Those works were consulted whenever it was necessary and possible, although no systematic lexical extraction was carried out. The main works consulted were the following: Berlin 1968 on numeral classifiers, Berlin et al. 1974 on ethnobotanics, Hunn 1977 on ethnozoology, Berlin and Berlin 1996 and Berlin 2000 on ethnomedicine, and other biologists’ studies where Tseltal names for living beings can be found along with their scientific identification; those references are cited in the corresponding entries of the TSMD.

The orthography used in the dictionary⇫¶

Tseltal orthography is officially normed by a document published as de Lenguas Indígenas 2010, which was the result of a series of meetings and workshops with Tseltal writers and bilingual teachers. This agreement differs little from what was already the common practice of most people writing the language. Tseltal orthography is globally similar to that of other Mayan languages, with a few specificities.

The following table displays the five vowels common to all Tseltal dialects.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i | u | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Low | a |

Table 2 presents the consonants of the phonologically most conservative dialect, Bachajón, using the practical orthography now commonly accepted among speakers and linguists. When this differs from IPA, the corresponding IPA symbol is given between slashes.

| Labial | Alveo-dental | Palato-alveolar | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | simple | p | t | k | ||

| ejective | p' | t' | k' | ' /ʔ/ | ||

| voiced | b | |||||

| Affricates | simple | ts /t͡s/ | ch /t͡ʃ/ | |||

| ejective | ts' /t͡s'/ | ch' /t͡ʃ'/ | ||||

| Fricatives | s | x /ʃ/ | j /x/ | h | ||

| Nasals | m | n | ||||

| Laterals | l | |||||

| Flap | r /ɾ/ | |||||

| Approximants | w | y /j/ |

Notes on consonants:

- Previously, <ts> and <ts'> used to be written <tz> and <tz'> respectively. Some linguists still follow that tradition.

- Some dialects (Oxchuc, Altamirano) lack /p'/, which merged with /b/ (cf. 6.2 below). This represents no orthographic issue, because the unique resulting phoneme /b/ is written as <b> (so for instance p’ij ‘wise’ is bij in Oxchuc and Altamirano).

- Most other dialects (all but Petalcingo) lack the opposition between /x/ (<j>) and /h/ (<h>), which historically merged. The resulting phoneme varies phonetically between [x] and [h], but it is uniquely transcribed as <j>.

- Some complications exist in the transcription of the glottal stop, because of two regrettable orthographic decisions: on the one hand, the decision to represent it orthographically with the same symbol used for ejective consonants (the apostrophe <'>), leading to potential confusions; and on the other hand, the decision not to write it at the beginning of words (preceding vowels). I’ll comment on these two cases and their consequences.

- Sequences of non-ejective stop/affricate + glottal stop are absent from basic roots, but a few of them arise through compounding or reduplication. In those cases, a different symbol must be used for the glottal stop to avoid confusion with the corresponding ejective stop/affricate: the symbol chosen by Tseltal writers has been the hyphen. This is the case in x'ujt-ujt /ʃʔuhtʔuht/ ‘flycatcher (bird)’, where two glottal stops can be observed: the second glottal stop cannot be transcribed with the normal apostrophe, because the orthographic sequence <t'> would be wrongly interpreted as the glottal alveo-dental stop /t'/, so a hyphen is used instead. This problem is absent with the first glottal stop in this word, as no ejective /ʃ'/ exists, so the sequence <x'> is correctly read as /ʃ+ʔ/.

- The hyphen is also used instead of the apostrophe after ejective consonants, such as ok'-on /ok’ʔon/ ‘whine’. With the hyphen here, a visually confusing sequence of two apostrophes is avoided, as would be x’ok’’on. The same applies to ach’-ach’tik /ʔat͡ʃ’ʔat͡ʃ’tik/ ‘half-new’ and ihk’ ihk’tik /ʔihk’-ʔihk’tik/ ‘blackish’.

- Concerning the beginning of words, the TSMD also aligns with a relatively bad practice, only because it is already well entrenched in the writing tradition of Mayan languages. It consists of not writing the prevocalic initial glottal stops. For example, /ʔiʃim/ ‘corn’ is written ixim, not ’ixim. This orthographic tradition comes from the fact that initial glottal stops at some point were considered only phonetic, among other reasons because they disappear after possessive/ergative prefixes, e.g. /kiʃim/ kixim ‘my corn’ {k- ‘1POS’} and because they are systematic (there are no roots initiating in vowel) and thus generally not contrastive. Unfortunately, in Tseltal there are some cases where they are contrastive: possessive/ergative prefix for second person is a(w)- without initial glottal stop (in most dialects), which creates minimal pairs with words initiating in /ʔa.../. For example, orthographic abak may correspond to /abak/ {a-bak ‘2POS-bone’} ‘your bone’ or to /ʔabak/ ‘soot’, which are phonetically distinguished in speech. Fortunately, this kind of ambiguity is infrequent in practice.

- When the phoneme /b/ is preceded by a vowel inside a word, that vowel tends to be laringealized, which amounts to hearing a glottal stop before the /b/. For example, abat ‘assistant’ may sound a’bat. This phenomenon is related to the fact that /b/ corresponded originally to the implosive /ɓ/, as it still is in other Mayan languages (especially in Guatemala), where it is written <b'>. Actual Tseltal dialects lost the implosive feature, but several dialects maintain to some degree the pre-laringealization associated with the constrained glottis feature. However, this phenomenon is not fully understood yet, as it is quite variable, both inter- and intra-dialectally, so the TSMD follows the INALI’s norm, which consists of not taking into account this pre-laringealization in the practical orthography. The only sequences written as V’b are those where the glottal stop belongs to the root and the /b/ to the first consonant of a suffix. This is the case for instance in ti'bal ‘meat’, from ti’ (t.v.) ‘eat (meat)’ and the nominalizer -bal.

Apart from those few cases, Tseltal orthography is rather straightforward.

Grammatical Categories⇫¶

In what follows, a very short sketch of each grammatical category used in this dictionary is presented. See Polian 2013a for further information on Tseltal grammar.

Nouns⇫¶

Class 1 and 2⇫¶

Two basic classes of nouns are distinguished in this dictionary: class 1 and class 2 (abbreviated as n. and n2. respectively): nouns of class 1 can be used without possessor, whereas class 2 nouns require a possessor, at least in their unmarked (non-suffixed) form. Some class 2 nouns can also appear non-possessed when they take an additional suffix, almost always a -Vl suffix, called “non-possession suffix”. The vowel of this suffix is not predictable and subject to dialectal variation and so it is indicated in each entry (e.g. nich'an, jol). Other class 2 nouns never appear non-possessed (e.g. buhts').

Beside the non-possession suffix, two other kinds of morphological information are indicated in some entries. First, some nouns (kinship terms) take a special plural suffix when they are possessed (e.g. al). On the other hand, many nouns display a marked possessed form, in which they take a -Vl suffix, in addition to the possessor prefix (e.g. ch'en, mut). Marked possessed form often indicates that the possessor is inanimate instead of animate. In other cases, it highlights that the kind of possession involved is non-canonical in some other way.

Action Nouns (act.n.) ⇫¶

Action nouns are a subtype of class 1 nouns. They denote agentive events, like a'tel or k'ayoj, and can be used in constructions where a non-finite verb is expected. Most of them are associated with an intransitive verb, although the morphological relation between action noun and verb is irregular. They also appear in a special construction as object of the verb a'iy, which emphasizes the agentive involvement of the subject.

A subtype of action nouns is incorporating action nouns (inc.act.n.). They are formally compounds with a transitive root or stem followed by a (notional) object noun (e.g. kuchsi', lik ha').

Relational Nouns (rel.n.)⇫¶

Relational nouns are a subtype of class 2 nouns: they are formally nouns that are always possessed. They are functionally equivalent to adpositions, as they are basically used as grammatical relators (e.g. u'un, bah, tojol).

Collective Nouns/Predicates (coll.)⇫¶

Lemmas classified as “collectives” are words derived with a suffix -tik, a suffix -Vl (variable vowel) or a combination of both (as -tik-Vl or -Vl-tik). They denote the abundance of the thing designated by the base, e.g. nichim ‘flower’ > nichimaltik ‘(place) full of flowers’. Their lexical classification is still problematic: in some of their uses they look like nouns, but at least in some dialects they do not behave like canonical nouns, in particular they cannot function as core verbal arguments, and they rather seem to be (both formally and semantically) diffusive adjectives (cf. 5.3 below). This is a topic for further research.

Verbs⇫¶

Verbs may be transitive (t.v.) or intransitive (i.v.). No basic ditransitive verbs exist in Tseltal, but all transitive verbs can be made ditransitive with the benefactive applicative -bey ~ be ~ b (e.g. ak'). Verbs may be finite or non-finite. The regular infinitives are derived with the suffix -el; they are considered part of the verb forms when they head a non-finite clause, but many of them can also be used as nouns and some head their own entry as such (e.g. koltayel, siht'ubel).

Finite verbs inflect for aspect and mood, marked by affixes and preverbal auxiliaries. Only auxiliaries have entries of their own (aux., e.g. ya, laj, k'an). An optional inflection category is pluractionality: there are special iterative and distributive forms for both transitive and intransitive verbs. Voice categories for transitive verbs are passive, antipassive, reflexive/reciprocal and the already mentioned benefactive applicative. Other valency-changing devices are derivational, like causative and anticausative.

Verbal inflection is very regular in Tseltal. The only verbs with some minimal irregularity are bah ‘go’ and k'oh ‘arrive’.

Several subclasses of verbs are identified in the dictionary:

- Agentive intransitive verbs (agt.i.v.) typically correspond to actions carried out by human beings (e.g. a'tej, k'ayojin). Most of them have an irregular non-finite form, instead of the regular infinitive in -el. The irregular forms correspond to action nouns (cf. 5.1.3 above).

- Some transitive and intransitive verbs are registered as defective (dev.t.v. and dev.i.v. respectively), because they are restricted in terms of the inflection categories (person, aspect-mood) they can combine with (e.g. tawan, xchih, tak').

- Movement and phasal intransitive verbs (mov.i.v. and phas.i.v. respectively) may function either as canonical intransitive verbs or as auxiliaries. In the latter case, they appear devoid of person marking and followed by a dependent form of the main verb, which carries person marking but no aspect. The exact construction is variable depending on the type of auxiliary (movement or phasal) and on the dialect.

- Several subclasses of transitive verbs are restricted to some particular pluractional or voice category, meaning that they always occur with that particular category (and its morphology): only distributive (tuts'tikla), only iterative (k'ipulan), only reciprocal (ch'ap), only reflexive (bonan), and only passive (e'tan), respectively abbreviated as distr.t.v., iter.t.v., recipr.t.v., refl.t.v., and pass.t.v..

Adjectives (adj.)⇫¶

Canonical adjectives (simply classified as adj., e.g. k'ixin, paj) can normally be found in two functions: as non-verbal predicates and as attribute modifiers of a noun. Some adjectives display only one of these functions: they are then classified as attr.adj. (only attributive adjective, e.g. ch'ul) or pred.adj. (only predicative adjective, e.g. p'ots).

Diffusive adjectives (diff.adj., e.g. abaktik) are a class of derived adjectives with a -tik suffix; when they are based on a CVC root, that root is reduplicated. Their semantics is attenuative or distributive (visually plural pattern). They are mainly used as non-verbal predicates.

Positional adjectives (pos.adj., e.g. balal) are a class of derived adjectives. They are all based on CVC roots and derived through a -Vl suffix (with vocalic harmony). Their semantics deals mainly with position (‘sit’, ‘stand’), disposition (‘lined up’, ‘heaped’) and/or shape (‘long’, ‘hollow’). Most of them have a special distributive plural form CVC-ajtik, indicated in each entry.

Morphology associated with adjectives:

- Some root adjectives take an extra -Vl suffix in attributive function (e.g. chi', sak). The exact form of this suffix is indicated in each entry (there may be several variants). When an adjective takes the attributive suffix only optionally, the possibility of the absence of any suffix is indicated by a slashed zero “∅”, followed by the overt form(s) of the suffix (e.g. pochan).

- Most adjectives derive an abstract noun with a -Vl suffix, which can be homophonous with the attributive -Vl suffix (e.g. chi', niwak) . With positional adjectives, the abstract noun is often derived directly from the CVC root with an -il suffix, instead of being formed on the CVC-Vl stem (e.g. balal).

Numerals and numeral classifiers⇫¶

With the exception of jun ‘one’, all numerals (num.) are morphologically complex: they consist of a numeral root plus another element, which is either the generic suffix -eb or a specific numeral classifier. In the TSMD, numerals are registered with the suffix -eb (e.g. cheb, oxeb). They derive an abstract noun which can be used as ordinal (like ‘second’) or quantifier (like ‘both’).

Numeral classifiers (num.clas.) are registered as bare stems (e.g. tuhl, ch'ix), but they cannot constitute independent words by themselves: they must combine with a preceding numeral root or undergo some derivational process. When they seem to be used alone, it is because they combine with j-, the reduced form of jun ‘one’, which is dropped in some dialects (cf. 6.7 below).

Some numeral classifiers are defective (def.num.clas.): they always take the numeral ‘one’ (j-), which is then integrated in their lemmatical form. They denote small amounts, like ‘a bit of...’ etc. (e.g. j'ohlil, jxuht').

Expressive predicates⇫¶

Expressives (expr.), otherwise known as “affect (words/verbs/predicates)” are a class of derived predicates, intermediate between verbs and non-verbal predicates, that highlight impacting sensorial properties of events (e.g. chajchon, kotlajan). They are based on CV(h/j)(C) roots, which can be of any other open lexical category or be properly expressive, often onomatopoeic. Additionally, they obligatorily take one of a series of dedicated suffixes that mainly encode information of aspect, pluractionality, and degree of emphasis.

Adverbs (adv.)⇫¶

Words classified as adverbs are free words that typically add information of space, time, manner, emphasis or modality, instead of predicating directly or acting as predicate arguments. This classification is only tentative and based on function, not on form, as there is no morphological uniformity among Tseltal adverbs. Many adverbs could probably be alternatively classified as non-verbal predicates or as some kind of adjective. Indeed, some adverbs are associated with an abstract noun suffix (e.g. niwak) just like adjectives are.

Incorporated adverbs (inc.adv.) appear inside the verbal complex before the verbal root, after the personal and/or aspectual prefixes, although most of them are orthographically written separated from the verbal root (e.g. ahnimal).

Other word classes⇫¶

- Coordinators (coord.): There are three coordinators: sok ‘and’ and the loanwords i ‘and’ and o ‘or’.

- Definite articles (art.): Three lemmas are classified as definite articles: te, i and me, of which the last two originate as demonstratives (cf. i and me, respectively). All those articles usually coincide with the suffixed determiners -e or -i.

- Demonstratives (dem.): This category covers locative and non-locative demonstratives (e.g. tey, me).

- Directionals (dir.): Directionals are based on nominalized intransitive movement verbs and one phasal verb (e.g. bahel, hahchel). They normally appear after a predicate or a spatio-temporal localizing expression to specify the trajectory or orientation, as well as to add aspectual nuances.

- Interjections (interj.): These are mainly greetings and address terms (e.g. awokoluk, ay).

- Interrogative/indefinite proforms (prof.): Under this label are registered interrogative pronouns, such as mach'a ‘who’, and proadverbs, such as banti ‘where’, etc. Those proforms function either as interrogatives or as indefinite (‘someone’, ‘in some place’, etc.), depending on the syntactic context.

- Non-verbal predicates (n.v.p.): This is a residual category for words that mainly function as predicates, but that do not qualify as verbs, nouns or adjectives. It includes for instance the existential/locative predicate ay.

- Onomatopoeias (onom.): Only a few onomatopoeias are registered in the TSMD (e.g. chak'). This lexical field has not been properly researched yet.

- Particles (part.): This is a residual category for different invariable elements, whose detailed classification is still pending. It includes second-position clitics and discourse particles, among others. Their functions cover aspectuality, tense, modality, etc. (e.g. a, awil).

- Personal pronouns (pro.): Only two groups of items are identified as personal pronouns. On the one hand, ha' (~ja') and its inflected forms. On the other hand, the possessed forms of tukel, which is also classified as relational noun.

- Prepositions (prep.): This group contains only two items: ta (general locative/instrumental preposition) and sok ‘with’.

- Quantifiers (quant.): In this group are included adverbs and/or non-verbal predicates whose function is to quantify, such as ‘a lot (of)’ or ‘a little bit (of)’ (e.g. bayel, mih). This is a very preliminary classification not yet supported by a detailed analysis.

- Subordinators (sub.): A few subordinators are registered in the TSMD, such as me ‘if’ or te ‘general subordinator’.

Coordinate compounds⇫¶

The only compounds identified as such in the TSMD are the coordinate compounds (or “co-compounds”), because they tend to be lexically anomalous: they usually lay somewhere between completely fused compounds and the coordination of independent words (this is not uncommon cross-linguistically, cf. Wälchli 2005). This means that their inflection may be variously and unpredictably distributed between both members of the compound. The following kinds of co-compounds are registered:

- Nominal co-compounds: n.co. and n2.co., depending on the noun class, cf. 5.1.1 (e.g. waj mats', me' tat).

- Verbal co-compounds, both transitive and intransitive: t.v.co. and i.v.co. (e.g. lap ch'ik, we' uch').

- Adjectival co-compounds: adj.co. (e.g. uts lek) and positional adjectival co-compounds: pos.adj.co. (e.g. jelel tasal).

- Adverbial co-compounds: adv.co. (e.g talel k'axel).

Phraseology⇫¶

Phrasemes have their own entries, with references to the corresponding entries of their constitutive parts. Phrasemes that function as predicates or as whole sentences are just identified as phr. Phrasemes may also be equivalent to a complex noun or adverb; those are abbreviated as n.phr. and adv.phr. respectively. Subsequently, an indication of the internal syntax of each phraseme is given in parentheses, e.g. “t.v.+obj.NP” describes a phraseme consisting of a transitive verb followed by an object NP (cf. la xt'ax sk'ab).

Predictable dialectal variation⇫¶

As a dialect dictionary, the TSMD is made up of many entries that subsume several dialect forms. That is, although each entry is headed by a unique lemma, other forms are indicated as dialectal alternative forms and the rest of the entry concerns any of those forms. Whenever it was possible to determine the most conservative form, that form was selected as lemma, as the other dialect forms can be deduced from it through the application of rules. In other cases, an arbitrary decision was made.

The dialectal variation concerning the phonology or morpho-phonology of particular words is partly predictable on the basis of the most conservative dialectal form, which generally coincides with that of Bachajón. For instance, if Bachajón presents a word starting with /h/, one can automatically deduce that, if another dialect like Tenejapa also displays this word, it will have /j/ instead of /h/. This kind of correspondence is defined in the TSMD as a set of seven parameters of predictable variation. These parameters, described below, allow merging together in one entry different forms under the same conservative lemma. Those seven parameters are indicated by abbreviations, which appear as the titles of the following sub-sections.

The "H"⇫¶

Proto-Tseltal distinguished a glottal fricative /h/ and a velar fricative /j/ (IPA: /x/). Only Bachajón and Petalcingo maintain this phonological opposition, whereas all other dialects have merged /h/ and /j/ (and the resulting phoneme is written <j>). But the developments of the proto-phoneme /°h/ were complex, as some dialects dropped it in several contexts instead of conserving it as /j/. The outcomes of /°h/ are well documented; the abbreviation “H” indicates that the /h/ present in the lemma gives way to the following phenomena.

- In initial position, all dialects but Bachajón have /j/ instead of /h/. Petalcingo is particular in this respect, because it is in the middle of the process of substituting /h/ with /j/ in initial position. This process is more advanced among younger speakers than among older ones. But in the TSMD only conservative forms (i.e., with initial /h/) are given for Petalcingo.

- Between vowels, some dialects maintain the outcome of /°/, as /h/ or /j/;

others drop it; a third group allows both possibilities, as in Table 3

Table 3: Outcomes of /°h/ in intervocalic position Conservation Loss Unstable Bachajón , Petalcingo Villa Las Rosas Center, Aguacatenango, Amatenango North (-Bachajón , -Petalcingo) ‘become bitter’ ch'ahub ch’ahub ch’ajub ch’aub ch’ajub ~ ch’aub ‘smoke’ ch'ahil ch’ahil ch’ajil ch’ail ch’ajil ~ ch’ail ‘down’ kohel kohel kojel koel kojel ~ koel - Some VhV sequences with identical vowels do not follow the preceding rule, but

tend to undergo a further reduction to V. This tendency is distributed over

dialects as illustrated in Table 4. Note that this phenomenon mixes with the

preceding one: no reduction only means that both vowels stay in place, but the

aspiration may be present, as /h/ or as /j/, or drop.

Table 4: Tendency to reduction of homorganic °VhV sequences in frequent words No reduction Optional reduction Reduction Bachajón,Petalcingo North (-Guaquitepec, -Sitalá, -Yajalón ) Center (Tenejapa) South Guaquitepec, Sitalá, Tenejapa , Yajalón ‘walk’ behen behen bejen been bejen ~ ben ben ‘name’ bihil bihil bijil biil bijil ~ bil bil ‘chasm’ xahab xahab xajab xaab xajab ~ xab xab - In word-final position two groups of dialects emerge: those that keep a reflex of /°h/ (either as /h/ or as /j/) and those that do not, as illustrated in Table 5.

- In Oxchuc, an /°h/ caused the ejectivization of a following non-ejective stop or affricate, as shown in Table 6.

- The proto-phoneme /°h/ dropped before sonorants (/m/, /n/, /l/, /w/ and /y/) and before the bilabial stop /b/ in all dialects but Bachajón, Petalcingo and Yajalón , and optionally in Chilón ; see Table 7 (Yajalón is omitted because /h/ further drops in non-final syllables, see below).

- In Villa Las Rosas, the /°h/ was elided before ejective consonants (both stops and affricates), as in Table 8.

- Finally, in Yajalón the reflexes of preconsonantic /°h/ drop everywhere but on the

last syllable of an intonation phrase. This has two consequences: 1) the /°h/

of °CVhCVC roots is always lost in Yajalón (e.g. °nehkel ‘shoulder’ gives

nekel); 2) the reflex of /°h/ in monosyllabic roots disappears when

the root is followed by any other syllable in the same utterance, for instance

when that root takes any suffix. This phenomenon is illustrated in Table 9.

Table 9: Reflexes of /°hC/ in Yajalón Conservation everywhere Conservation in utterance-final position Other dialects Bachajón, Petalcingo Yajalón Guaquitepec, Cancuc, Amatenango,... ‘shoulder’ nehkel nehkel nekel nejkel ‘thunder’ t'ohm t’ohm t’ojm t’om ‘s/he fell’ yahl yahl yajl yal ‘I fell’ (-on 'suj1sg') yahlon yalon yalon ‘s/he went’ bah baht bajt bajt ‘s/he already went’ (-ix ‘already’) bahtix batix bajtix

| Conservation | Loss | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bachajón, Petalcingo | North (-Bachajón, -Petalcingo), Cancuc, Tenango, Villa Las Rosas | Central (-Cancuc, -Tenango) | |

| ‘go down’ koh | koh | koj | ko |

| ‘look for’ leh | leh | lej | le |

| ‘spicy’ yah | yah | yaj | ya |

| With ejectivization | Without ejectivization | |

|---|---|---|

| Oxchuc | other dialects | |

| ‘shoulder’ nehkel | nejk’el | nehkel,... |

| ‘wound’ ehchen | ejch’en | ehchen,... |

| ‘go’ bah | bajt’ | baht,... |

| Conservation | Variable | Loss | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bachajón, Petalcingo | Chilón | Center, South, Guaquitepec, Sibakja', Sitalá | |

| 'thunder' t'ohm | t’ohm | t’ojm | t’om |

| 'middle' ohlil | ohlil | ojlil | olil |

| 'cough' ohbal | ohbal | obal | obal |

| Loss | Conservation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Villa Las Rosas | Bachajón, Petalcingo | other dialects | |

| ‘dance’ ahk'ot | ak’ot | ahk’ot | ajk’ot |

| ‘swell’ siht' | sit’ | siht’ | sijt’ |

| ‘tasty’ buhts'an | buts’an | buhts’an | bujts’an |

"P"⇫¶

The abbreviation P’ stands for the phenomenon whereby all instances of /p’/ correspond to /b/ in Oxchuc, as illustrated in the table. Furthermore, an /°h/ caused the ejectivization of a following /p/ in Oxchuc (cf. Table 6), which subsequently became /b/, as illustrated in the last row.

| Without neutralization all dialects but Oxchuc | Neutralization Oxchuc | |

|---|---|---|

| ‘wise’ p'ij | p’ij | bij |

| ‘pine bark’ p'alax | p’alax | balax |

| ‘merchandise’ p'olmal | p’olmal | bolmal |

| ‘crab’ nep' | nep’ | xneb |

| ‘be resolved’ chahpaj | chahpaj~chajpaj~chapaj | chajbaj |

"-Y"⇫¶

Several derivative suffixes end in /y/, like the transitivizer suffixes -(C)Vy ( -tay, -liy, -iy, -uy), the iterative suffix -Vlay and the suffix -ey that derives temporal adverbs. The final /y/ of all these suffixes tends to drop at least in some contexts in all dialects. The only exception is Villa Las Rosas, where this elision seems absent. Most dialects tend to elide this /y/ before a consonant, i.e. when the word takes another suffix that starts with a consonant; some others also elide it when the referred suffix ends the word (before the final word boundary). Finally, Tenejapa tends to elide it always (i.e. it is close to losing this segment altogether in those suffixes). Note that this is just a gross approximation, as we are dealing here with tendencies on a continuum.

This phenomenon is illustrated in Table 11 with forms of the verb koltay ‘help’, where the elision of the final /y/ is at stake: before a vowel with suffix -on ‘OBJ1SG’, at the end of the word with a null third person object and before a consonant with suffix -tik ‘plural of a first person subject’.

| Elision: | Minimal | Before consonants only | Before consonants and word boundary | Maximal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dialects: | Villa Las Rosas | North (-Bachajón, -Petalcingo); Central (-Tenejapa), Amatenango | Aguacatenango, Bachajón, Petalcingo | Tenejapa |

| ‘s/he helps me’ | ya skoltayon | ya skoltayon | ya skoltayon | ya skoltaon |

| ‘s/he helps her/him’ | ya skoltay | ya skoltay | ya skolta | ya skolta |

| ‘we help her/him’ | ya jkoltaytik | ya jkoltatik | ya jkoltatik | ya jkoltatik |

"Vj"⇫¶

Many intransitive verbs are derived with a suffix -ij / -uj, which comes sometimes with a preceding consonant, as -Cij / -Cuj (e.g. -k’ij / -k’uj, etc.). In these suffixes, the vowel is phonologically determined by the root vowel: if the root vowel is /o, u/ the suffix is -(C)ij, whereas if the root vowel is /a, e, i/ the suffix takes the form -(C)uj. Now, some dialects display other vowels in these suffixes. Namely, Center and Amatenango have -(C)ej instead of -(C)ij, and Amatenango, Cancuc, and Tenejapa have -(C)oj in place of -(C)uj. Both cases can be analyzed as a lowering of the vowel caused by the final velar fricative /j/. This is summarized in Table 12.

| Basic form | Lowering of /i/ | Lowering of both /i/ and /u/ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abasolo, Oxchuc, Tenango, San Pedro Pedernal | Amatenango, Cancuc, Tenejapa | ||

| ‘be scattered’ (busk'ij) | busk’ij | busk’ej | busk’ej |

| ‘roll’ (balch'uj) | balch’uj | balch’uj | balch’oj |

"O/U"⇫¶

Several suffixes display a dialectally variable vowel: it may be /o/ or /u/. It is not clear which one is historically anterior. For instance, a common derivation for expressive predicates (see 5.5 above) consists of a suffix -{C}Vn where {C} is a copy of the root initial consonant and V alternates between /o/ and /u/ depending on the dialect (cf. chajchon~chajchun ‘sound repeatedly as steps in dry leaves’).

Some dialects consistently select either /o/ or /u/ in all the concerned suffixes: for example Cancuc has /o/, whereas Amatenango, Petalcingo, and Tenejapa always prefer /u/. But other dialects display some indeterminacy, as Bachajón and Oxchuc, where the selection is lexically determined. However, the dialectal distribution of this phenomenon has not been completely documented yet.

In the dictionary, the forms with /o/ have been chosen in the lemmas, and the other possibility is indicated below with the abbreviation “O/U”. This is an arbitrary decision. Other examples can be observed in ah'on, buhyom, ech'om, and jisomtay.

“-tVmba”⇫¶

The reciprocal nominalizer suffix is -tamba or -tomba depending on the dialect, with a variable /a/~/o/ vowel: in North and Villa Las Rosas it is always /a/ (e.g. miltamba ‘mutual killing’, from mil ‘kill’), whereas in Center and Amatenango it is exclusively /o/ (miltomba), with the exception of Tenejapa where /a/ and /o/ alternate (information is lacking for Aguacatenango). This is summarized in Table 13.

| North, Villa Las Rosas | Center, Amatenango | Tenejapa/th> | |

|---|---|---|---|

| /a/ | /o/ | /a/~/o/ | |

| ‘mutual killing’ miltamba | miltamba | miltomba | miltamba~miltomba |

| ‘fight’ majtamba | majtamba | majtomba | majtamba~majtomba |

As a-forms of this suffix are more widely spread, those were selected for lemmas in the dictionary.

"J-"⇫¶

There are three homophonous prefixes j-:

- The agentive prefix, which derives a person-denoting noun from action nouns, as elek’ ‘theft’ > j’elek’ ‘thief’.

- The masculine nominal class, which appears with proper nouns, as jPetul ‘Peter’ and some names of animals and plants (the feminine counterpart of this prefix is x-).

- The reduced form of the numeral jun ‘one’ in combination with numeral classifiers (cf. 5.4), as jch’ix ‘one long thing’.

These prefixes were completely lost in Guaquitepec and Oxchuc, and are only optionally used in Cancuc and San Pedro Pedernal. Therefore, in those dialects elek’ means either ‘theft’ or ‘thief’. In the dictionary, the prefixed forms were preferentially registered.

Abbreviations⇫¶

| act.n. | action noun |

| adj. | adjective |

| adv. | adverb |

| agt. | agentive |

| art. | definite article |

| attr. | attributive |

| clas. | classifier |

| co. | co-compound |

| coord. | coordinator |

| def. | defective |

| dem. | demonstrative |

| diff. | diffusive |

| dir. | directional |

| expr. | expressive |

| i. | intransitive |

| inc.act.n. | incorporating action noun |

| inc.adv. | incorporated adverb |

| interj. | interjection |

| mov. | movement |

| n. | noun |

| n.v.p. | non-verbal predicate |

| num. | numeral |

| onom. | onomatopoeia |

| part. | particle |

| phas. | phasal |

| pos. | positional |

| pred. | predicative |

| prep. | preposition |

| pro. | personal pronoun |

| prof. | interrogative/indefinite proform |

| quant. | quantifier |

| rel. | relational |

| sub. | subordinator |

| t. | transitive |

| v. | verb |

Acknowledgements⇫¶

The following institutions funded the general documentation project, of which the TSMD was a part of:

- ELDP/SOAS, through the Field Trip Grant 0114 (2006) and the Major Documentation Project 0164 (2007-2010).

- The CONACYT (Mexican National Council of Science and Technology), through the SEP-CONACYT fund for basic research.

- The INALI (Mexican National Indigenous Languages Institute).

- The Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics.

- CIESAS-Sureste, where this project was hosted.

Roberto Sántiz Gómez donated 69 drawings, which he had asked the artist Antun Kojtom to make for his MA research on positional adjectives (cf. Sántiz Gómez 2010).

Gabriela Torres Freyermuth contributed to the collection and selection of photographs as part of her social service, along with Antonia Sántiz Girón.

External Link⇫¶

An updated version of the Tseltal-Spanish database, with added audios and illustrations, is available at http://ditsel.aldelim.org/.

| Full Entry | Headword | Part of Speech | Meaning Description | Dialectal Distribution | Comparison Meaning | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Text | Analyzed Text | Gloss | Translation | IGT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Details | Name | Title | Year | Author | BibTeX type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|